FBI wants to keep fortune in cash, gold, jewels from Beverly Hills raid. Is it abuse of power?

When FBI agents asked for permission to rip hundreds of safe deposit boxes from the walls of a Beverly Hills business and haul them away, U.S. Magistrate Steve Kim set some strict limits on the raid.

The business, U.S. Private Vaults, had been charged in a sealed indictment with conspiring to sell drugs and launder money. Its customers had not.

So the FBI could seize the boxes themselves, Kim decided, but had to return what was inside to the owners.

“This warrant does not authorize a criminal search or seizure of the contents of the safety deposit boxes,” Kim’s March 17 seizure warrant declared.

Yet the FBI is now trying to confiscate $86 million in cash and millions of dollars more in jewelry and other valuables that agents found in 369 of the boxes.

Prosecutors claim the forfeiture is justified because the unnamed box holders were engaged in criminal activity. They have disclosed no evidence to support the allegation.

Box holders and their lawyers denounced the ploy as a brazen abuse of forfeiture laws, saying prosecutors and the FBI were trampling on the rights of people who thought they’d found a safe place to stash confidential documents, heirlooms, gold, rare coins and cash.

If the FBI wanted to search the boxes, the lawyers say, it first needed to meet the standard for a court-issued warrant: Probable cause that evidence of specific crimes would be found.

The government “can’t take stuff without evidence in the hopes that you’re going to get it later,” said Benjamin Gluck, an attorney who represents box holders suing the government to retrieve their property. “The 4th Amendment and the forfeiture laws require the opposite — that you have the evidence first, and then you can take property.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Forfeiture laws enable the government to confiscate assets tied to criminal activity. The generally low standard of proof makes it an appealing tool for prosecutors, who in criminal trials must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

FBI spokeswoman Laura Eimiller referred questions to the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles.

Thom Mrozek, a spokesman for the office, denied the government was misusing its powers by trying to confiscate box holders’ belongings.

“We have some basis to believe that the items are related to criminal activity,” he said.

In general, Mrozek said, a number of factors would lead the FBI to pursue forfeiture of the boxes’ contents — such as large stacks of cash kept by a person with a criminal record or no known source of income.

Possession of cash in any amount is legal.

Beyond the $86 million in cash, the FBI is seeking to confiscate thousands of gold and silver bars, Patek Philippe and Rolex watches, and gem-studded earrings, bracelets and necklaces, many of them in felt or velvet pouches. The FBI also wants to take a box holder’s $1.3 million in poker chips from the Aria casino in Las Vegas.

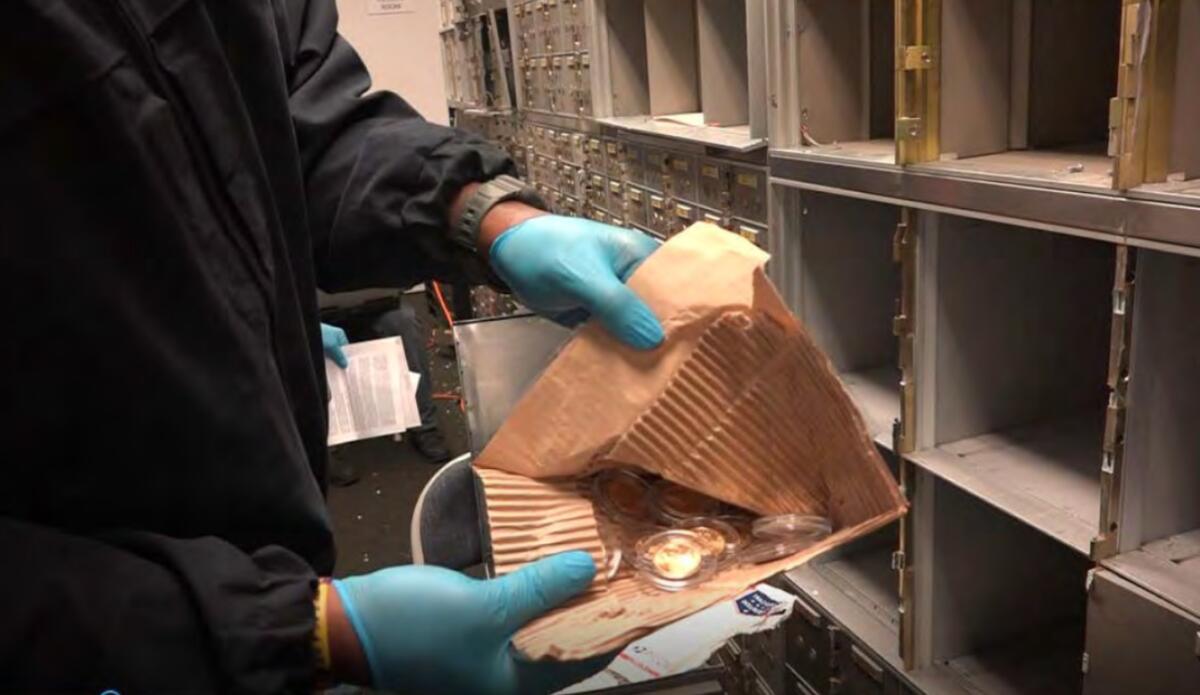

The money and goods are among the contents of about 800 safe deposit boxes the FBI seized in late March during a five-day raid of the U.S. Private Vaults store in an Olympic Boulevard strip mall known for its kosher vegan Thai restaurant.

The FBI has returned the contents of about 75 boxes and plans to give back the items found in at least 175 more, because there was no evidence of criminality, Mrozek said. Federal agents have not determined who owns what was stored in many other boxes.

The indictment says U.S. Private Vaults marketed itself to attract criminals who wanted to store valuables anonymously and keep tax authorities at bay. An owner and a manager of U.S. Private Vaults were involved in drug sales, it says, and co-conspirators helped customers convert cash into gold to evade government suspicion.

Among those ensnared in the government’s dragnet was Joseph Ruiz, who lost his life savings in the raid: $57,000 in cash. An unemployed food service worker who lives near Crenshaw Boulevard and the 10 Freeway, Ruiz, 47, distrusts banks and sees world affairs as deeply unstable, so he kept his money at U.S. Private Vaults.

He obtained the money in two legal settlements, one for a spinal injury in a car accident and another for chronic housing code violations in his apartment building, Ruiz said.

The FBI seized it, rejected his requests to return it and is now moving to confiscate it without explanation.

“They just kind of stole my money,” said Ruiz, whose most recent job was at Gate Gourmet, an airline caterer.

When he stopped by U.S. Private Vaults during the FBI raid to claim his money, Ruiz said, a federal agent asked if he belonged to a drug cartel.

“I’m made out to be a criminal, and I didn’t do anything,” said Ruiz, the son of a retired Los Angeles police officer. “I’m a law-abiding citizen.”

Ruiz has joined Jennifer and Paul Snitko, a Pacific Palisades couple who kept jewelry and baptism certificates in their U.S. Private Vaults box, in filing a class-action complaint against Tracy L. Wilkison, the acting U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, and Kristi Koons Johnson, who heads the FBI’s L.A. field office.

It is one of 11 suits filed by box holders that seek the return of their property and court orders declaring the seizures unconstitutional.

“They throw people like Joseph into this upside-down world where they did nothing wrong, but they’re forced to come forward to litigate against the government just to get their property back and prove their own innocence,” said Robert Frommer, an attorney for Ruiz and the Snitkos.

Five lawsuits say FBI overstepped its powers by seizing contents of hundreds of safe deposit boxes

Frommer is a senior attorney at the libertarian Institute for Justice in Virginia, where he specializes in challenging government forfeitures.

Forfeiture is a controversial tool used heavily in recent decades by federal, state and local law enforcement agencies nationwide. Proponents say it deters crime with the threat that cash, cars and other property acquired illegally, or used for illicit purposes, might be confiscated.

Critics, however, say it is often abused by police and prosecutors who can seize people’s property even if they lack evidence to prove their guilt in a criminal trial. Many jurisdictions have faced accusations of excessive use of forfeiture to fund law enforcement operations.

From 2000 to 2019, forfeitures generated $46 billion for the federal government, an Institute for Justice report found.

In the U.S. Private Vaults case, the FBI’s May 20 notice of forfeiture against 369 safe deposit boxes marked a major escalation of what was already a raw display of power by the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles.

“This definitely doesn’t smell good,” said former federal prosecutor David B. Smith, the author of “Prosecution and Defense of Forfeiture Cases.” “They can’t say, ‘you show me this is legitimate money’ — that’s not the law, and no judge is going to let them do that.”

Box holders who fail to claim their property in the next few weeks will automatically lose it. Those who challenge the confiscation have two choices.

One route is to concede that the FBI has a right to take their money or valuables and request return of at least a portion. The other is to contest the forfeiture by June 24, which would require the government to show evidence in court linking the property to crime. The risk of high legal fees often deters people from filing claims.

Jeffrey B. Isaacs, an attorney for box holders, said prosecutors were trying to “extort people into exposing their identities in order to investigate them.” “It’s unprecedented, and I think it’s very dangerous,” he said.

In their lawsuits, box holders claim the FBI is forcing them to give up either their Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures or their Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate themselves.

The government’s intent all along, their lawyers say, was to search every box — in defiance of the magistrate’s warrants — for evidence against the customers.

From the start, the raid on U.S. Private Vaults posed challenges for the FBI.

The case that agents built against the business appeared to offer ample grounds for a court to authorize seizure of the company’s computers, security cameras and other business equipment — including the hundreds of safe deposit boxes lining its walls.

In seeking warrants for the raid, prosecutors and FBI agents acknowledged they had no legal power to search each box for evidence of crimes. They assured the magistrate they would not overstep constitutional limits.

“The warrants authorize the seizure of the nests of the boxes themselves, not their contents,” FBI agent Lynne Zellhart told Kim, underlining “not” in her sworn statement requesting search and seizure warrants. “By seizing the nests of safety deposit boxes, the government will necessarily end up with custody of what is inside those boxes initially.”

Zellhart vowed the FBI would make a careful record of each box’s contents, following its written inventory policies to protect the government against claims of theft or damage and to ensure nothing hazardous was stored.

She told the magistrate that agents would “inspect the property as necessary to identify the owner and preserve the property for safekeeping.” Under FBI policy, she wrote, the inspection “should extend no further than necessary to determine ownership.”

The FBI’s legal handbook for agents describes inventory searches as a caretaking function. Agents must not use them as a ruse for a “general rummaging” to find evidence of crimes, the Supreme Court has ruled.

They are allowed to seize contraband or evidence that can clearly lead to the apprehension and conviction of a suspect for a specific crime. Fentanyl, OxyContin, and guns were found in boxes at U.S. Private Vaults, according to the FBI.

Still, Gluck said a 44-minute “video inventory” of FBI agents rifling through the box of an 80-year-old client “puts the lie” to the government’s promises to the magistrate. In the first minute, he said in court papers, agents hold up a document with the woman’s contact information to the camera, then go on to open a series of sealed envelopes and “carefully photograph every page and Post-It note in the box.”

In addition, he said, the FBI’s “chaotic and slapdash” inventory of her valuables neglected to include $75,000 in gold coins that she has now sued to recover.

Beverly Hills store let criminals stash guns, drugs and cash in vault at strip mall, prosecutors say

An FBI and DEA raid of an Olympic Boulevard strip mall found safe deposit boxes crammed with contraband, indictment says.

The government, which returned everything else she said was in her box, disputes the claim of missing coins, Mrozek said. At least two FBI agents were present for all box inspections, which were each photographed or videotaped, he added.

“We think that we’ve done the best job possible in accounting for all of the items,” he said.

Drug-sniffing dogs at the store during the raid alerted to traces of drugs on most of the money found in boxes, FBI agent Justin Palmerton claimed in a court statement. The boxes containing that cash are subject to criminal investigation, he said.

The reliability of dogs sniffing cash for drug residue is a longtime source of court disputes.

A dog alert alone is insufficient evidence of a drug crime to warrant forfeiture of cash, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 1994. The court cited testimony that 75% of the currency circulating in Los Angeles was tainted with cocaine or other illegal drugs.

The cash the government is trying to confiscate was taken from 353 boxes in amounts ranging from $5,000 to $2 million, according to the FBI. Mrozek declined to say if any of the allegations of criminal activity were based solely on dog alerts.

Daniel Paluch, 38, was living near the U.S. Private Vaults store a couple years ago when he decided it would be a good spot to store his passport, Social Security card, vaccination records and a few family treasures.

A week after the raid, he told assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew Brown, who is prosecuting U.S. Private Vaults, that he was eager to recover a bracelet his grandmother hid from the Nazis during her internment at Majdanek concentration camp.

“It will be difficult for my family and me to stomach damage or loss of most of the items in my box,” Paluch wrote in an email.

Brown responded: “Please rest assured that the contents of your box are safe and secure, and that we want to return all legitimately held items to their rightful owners.” He told Paluch the FBI was vetting all box holders’ claims and urged him to gather records on the items he stored.

Paluch, a Century City lawyer, had no receipt for the bracelet. He told Brown he was “at a bit of a loss as to what records I need” to get it back. He requested a copy of the warrant agents had used to seize his property and of the receipt for what was taken — both standard documents in any government search.

Brown replied that Paluch was not entitled to a copy of the warrant served on U.S. Private Vaults and that he would need to plead his case to the FBI.

“I was not offering to be a liaison between you and the FBI,” Brown wrote. “My suggestion that you gather relevant records was mere common sense. I do not know what procedures the FBI will employ to vet claims; your ideas are as good as mine.”

The FBI ultimately returned Paluch’s valuables. But like Ruiz, he felt violated. While he has nothing to hide, he said, “I don’t like the government’s magnifying glass being on me.”

“They went on a fishing expedition,” Paluch said. “They painted us all with this broad brush as criminals.”

Times Staff Writer Maloy Moore contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.