Compton could make history by electing its first Latino mayor, marking a milestone for the city and region

At his campaign headquarters near Compton City Hall, Cristian Reynaga scrolled through photos of signs supporting his bid for mayor.

They had been torn down and in some cases plastered with insulting messages.

If elected Tuesday, Reynaga would be the city’s first Latino mayor — and, at 26, its youngest.

Compton became majority Latino years ago, but power is still largely in the hands of Black politicians.

The city remains a touchstone of Black culture in the popular imagination, from the rise of the rap group N.W.A, depicted in the film “Straight Outta Compton,” to tennis stars Venus and Serena Williams, who honed their craft on the courts of East Compton Park.

Reynaga’s election would mark a milestone not just for Compton but for a region where Latino political power has often lagged behind demographic change.

Reynaga said he does not know who vandalized his campaign signs, but he attributes the motivation to the city’s cutthroat politics, not racial animus.

He downplays any talk of racial milestones.

“I never really saw it as a race thing,” Reynaga said. “I don’t want to be known as a Latino mayor ... I want to be known as a mayor who had a positive change, but I do take pride that I speak Spanish.”

Politics in Compton is more personal than racial, some observers say. Cross-racial alliances are common.

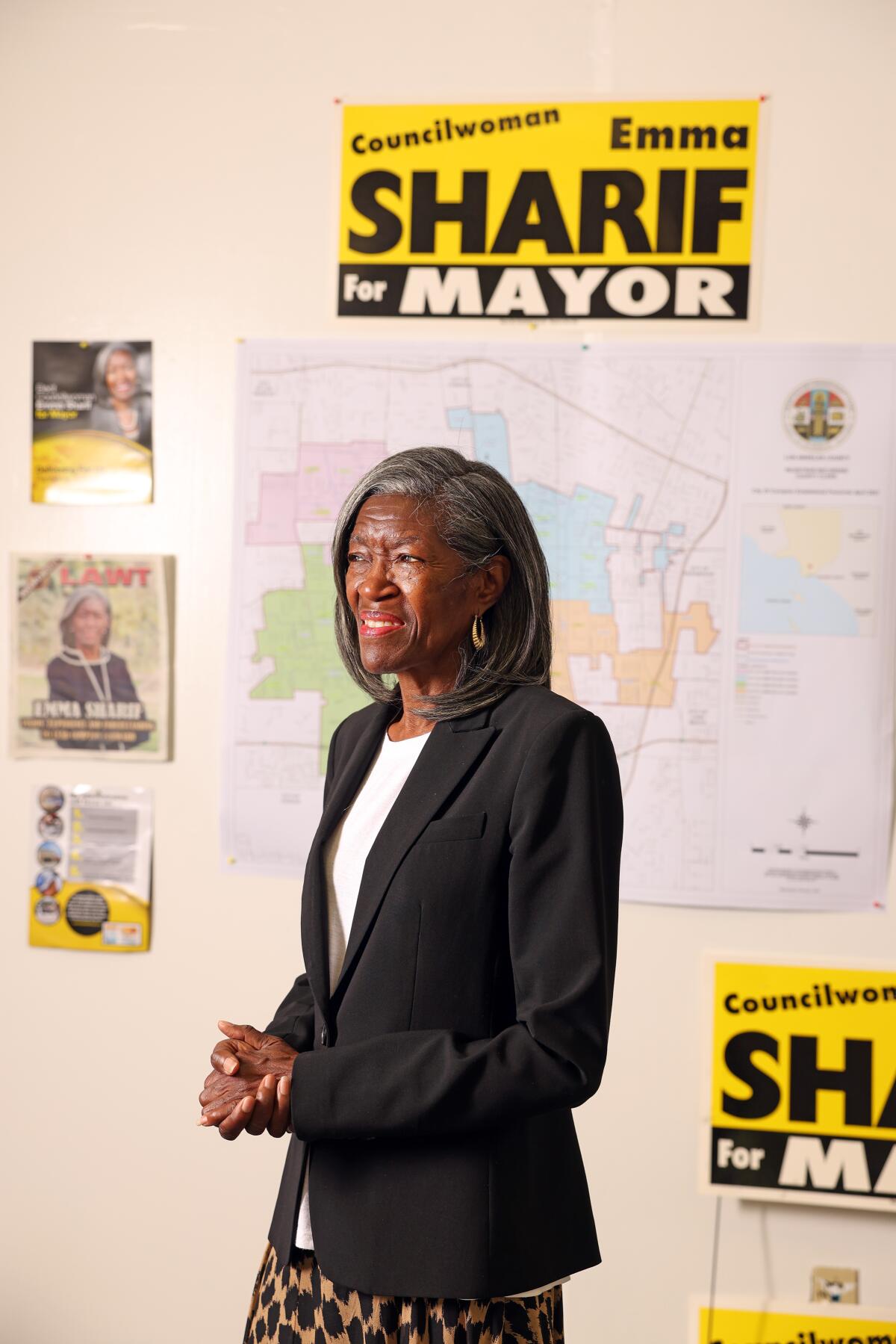

In a prominent example of such an alliance, the outgoing mayor, Aja Brown, has endorsed Reynaga over his opponent, 70-year-old City Councilwoman Emma Sharif.

Brown and Sharif are both Black. Brown has mentored Reynaga and has not seen eye to eye with Sharif on some issues.

Sharif, meanwhile, has several key Latino supporters, including the congresswoman who represents the area.

Legrand H. Clegg II, a former Compton city attorney, said “interracial leadership” is becoming the norm.

“People are less likely to look at the color of your skin and more at your deeds,” he said.

At the same time, he said, some Black residents fear losing their hard-won political power.

“African Americans fought bitterly for power in Southern California and across America,” Clegg said. “So when we’ve gotten it, we’ve jealously held on to it because it’s so elusive in terms of the ability to keep it.”

The city’s new mayor will have to address issues with law enforcement, homelessness and economic development, as well as voter demands to repair the streets and plant more trees and flowers.

Many residents say they feel under siege by the people who are supposed to protect them.

Reynaga, a Realtor and entrepreneur who grew up in the city, finished first in the April 20 primary against nine opponents.

He won 31% of the vote to 19% for Sharif, who served on the board of the Compton Unified School District before joining the City Council in 2015.

Turnout was about 16% among the city’s more than 49,000 registered voters, with the vast majority of ballots cast by mail.

Reynaga is trying to capture a citywide vote that has not historically favored Latino candidates, even though Latinos are 68% of the population compared with Black people at 29%.

As is typical with heavily immigrant groups, such as Asian Americans in the San Gabriel Valley, some Latinos are not citizens, are not registered to vote or are not engaged in local politics.

After a generational lag, political representation has caught up with demographics in some cities, including Monterey Park, where four of the five council members are Asian American.

Compton has yet to see such a shift.

In 2010, three Latinas sued the city, alleging that at-large City Council elections weakened Latinos’ voting power.

In 2013, a year after voters approved elections by district, Isaac Galvan became the first Latino on the City Council, which includes the mayor as one of its five members. He remains the only Latino council member.

Galvan is up for reelection Tuesday, after finishing second in the primary to Andre “HubCityDre” Spicer, who is Black.

In November, Galvan’s apartment was searched by federal investigators as part of a probe into corruption in the Baldwin Park city government. Galvan has said the inquiry has nothing to do with Compton City Hall.

Reynaga serves on two city commissions and has been interested in local government since he began attending council meetings at age 8, he said. As he embedded himself in Compton politics, many of the leaders he worked with were Black Americans.

His stated priorities — among them homelessness, illegal dumping and public safety — do not differ drastically from his opponent’s.

Like many American cities, Compton has seen a huge increase in homicides during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 17 through April, compared with four last year.

Sharif says she wants to tackle homelessness and hold the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department accountable for deputy shootings of civilians and other issues.

She said she has voted on measures in favor of tree trimming, graffiti removal and street repair contracts.

Since the beginning of the year, Sharif has raised more than $41,000, compared with about $28,000 for Reynaga.

Sharif’s donors include Crystal Casino and Republic Services, the city’s trash hauler. Reynaga’s campaign war chest comes largely from his own pocket.

Brown, who was 31 when she took office, brought a youthful glamour to the post as she pushed for Compton to be known as more than a hotbed of gang violence.

Under her leadership, the city saw a flood of new development and positive press.

Brown started a gang intervention initiative and mandated that 35% of workers on city-funded projects come from the community. She built ties with celebrities who grew up in the city, like Kendrick Lamar and Dr. Dre, prompting them to pump millions of dollars into local programs. But she and the council faced criticism a few years ago for payments of more than $3,000 a month each was collecting for attending commission meetings. After an inquiry by the L.A. County district attorney’s office and a state audit, they eventually reduced their pay to comply with the city charter.

When the ragged, faded tennis courts needed to be fixed, Compton turned to one thing that the city has a bounty of: celebrities.

In January, Brown announced she would not seek a third term.

Some residents are tired of the drumbeat of financial issues from the city government.

They say they want the city to address basic needs such as street repairs, tree trimming and graffiti removal and will vote for whoever can do a better job, regardless of race.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re white, blue, green, Chinese or whatever,” said Charlotte Davis, 67, a longtime resident. “They just need to do right by the people.”

Adding to the frustration are property tax rates that are among the highest in Los Angeles County.

“And we have nothing to show for it,” said Donna Baylor, 62.

Charles Davis, a board member of the Compton Unified School District, said he supports Sharif because he has worked with her and believes she has good ethics.

“With her we know what we’re getting,” said Davis, who is Black and was the Compton city clerk for 30 years. “With him, it’s not known, and being young and being the first Latino, to me, that’s not a reason. Making history [is] not a reason.”

Tito Palomares, a longtime Compton resident who is Latino, cast his vote for Reynaga last week.

“I was just trying to vote for change [and] trying to see if he can make a difference,” he said.

Palomares, 37, voted for Brown in 2013 because she wasn’t an incumbent. Her endorsement didn’t influence his decision to support Reynaga, he said.

Some Latino voters are eager to see a fellow Latino in charge of the city.

Francisco Ramirez, 56, voted for Reynaga last week because he values a newcomer’s youthful energy. A Latino mayor in Compton “is a long time coming,” he said.

“I want someone to come in and just go for it, whether it’s a hit or miss,” said Ramirez, who has lived in the city for three decades.

In an example of political support crossing racial lines, Sharif has been endorsed by Congresswoman Nanette Barragán (D-San Pedro), whose district includes Compton, and the Chicano Latino Immigrant Democratic Club of Los Angeles County.

“She knows the community,” said Martin Cruz, president of the Democratic club. “She knows [it] on the political side and also on the school side because she was on the school [board].”

The club educates Latinos on the importance of voting but does not limit its endorsements to any ethnic group, he said.

Brown got some blowback on social media for endorsing a Latino candidate over Sharif.

But she has taught Reynaga the political ropes. He worked for her campaign in 2013, and she nominated him to the Compton Taxpayers Committee. She said Reynaga loves the city and will unify the council to get things done.

“I just really believe that at this time the city could benefit from just a change in leadership across the board,” Brown said.

City observers say Sharif is known for being somewhat of a wildcard in her council votes. She says she is proud of her independence.

“Honestly, I’ve enjoyed being in that position a lot because what it does is that it kept me where I was always focused on the goal, and the goal was to provide a service to the community,” she said.

Sharif was born to sharecroppers in Forrest City, Ark.

At 15, she was part of a small group of Black students who integrated an all-white high school. The experience shaped her resolve not to cave in to pressure and deepened her work ethic, she said.

She moved to Compton three decades ago and was the first in her family to graduate from college, earning a political science degree from Cal State Dominguez Hills.

She joined the school board in 2001, serving for 14 years. In 2015, she won a seat on the Compton City Council and was reelected in 2019.

She said she has worked closely with Latinos and will give equal attention to all residents.

“My thing is to represent the city, and that means I have to support everybody,” she said. “It doesn’t matter who you are.”

Reynaga grew up in the Richland Farms neighborhood, home to the Compton Cowboys, and worked at the stables as a child. Sometimes, he crammed into his aunt’s apartment with his mother and sister. There was little money for new clothes or shoes.

His aunt, Josie Reynaga, encouraged him to get involved in community service and local government at a young age, he said. His grandmother also emphasized the importance of voting.

“She would have to ride a horse into the main city [in Mexico] — it’d be like a two- or three-day trip — and then ride back,” he said. “So for her to go vote, it would take a week.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.