Many Latino men haven’t gotten vaccinated. Misinformation, fear and busy lives are factors

When Crystal Rodriguez made an appointment for the Pfizer vaccine at a local clinic, her husband was hesitant to join her. He relented after a little nudging.

They both received their first dose with few side effects. Rodriguez felt a sense of relief as she went about her daily routine with her three children.

But by the time they were due to schedule their second dose, Rodriguez’s husband had been influenced — by his peers, by social media, she was not sure exactly what.

“Somebody got to his head,” the 33-year-old East Los Angeles resident said. Her husband refused to go.

Nationally, a third of unvaccinated Latinos say they want to get the shot as soon as possible — a much higher share than unvaccinated Black or white people, according to a survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

They are eager to put an end to the pandemic that has disproportionately impacted their community with high rates of illness and death as well as financial struggles.

But many are concerned about missing work because of side effects, have transportation difficulties or mistakenly believe they might have to pay for the vaccine, the Kaiser survey showed.

Vaccination rates are especially low among Latino men. In L.A. County, 39% had gotten at least one shot, compared to 59% of white men, as of May 9. Across demographics, women are more likely to get vaccinated than men, with about 46% of Latina women having gotten a shot.

Healthcare advocates are zeroing in on the issues that prevent Latino men from getting vaccinated, which range from misinformation to busy schedules, lack of familiarity with the healthcare system and fear of side effects.

Campaigns such as #VacunateYa on social media aim to educate people about the vaccines. Last Thursday, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced a bilingual vaccination campaign featuring celebrities such as actor Danny Trejo, music legend Pepe Aguilar and telenovela star Angélica Maria.

With Latinos making up nearly half of L.A. County and 39% of the state’s population, much is riding on the efforts. Latinos of both sexes have lower vaccination rates than whites and Asians and are about on par with Black residents statewide.

Ilan Shapiro, a physician involved in #VacunateYa, said communicating vaccination information to Latino audiences involves not just translating into Spanish, but connecting culturally and earning their trust.

Latino men are less likely to have health insurance or be health conscious compared to Latina women and to men in other demographics, he said.

Women are more often in need of emergency care for pregnancy, their children or other health issues, which builds a connection with the healthcare system. For men, that connection isn’t always there, so a visit to the doctor often happens only as a last resort.

“Men are not that good at going back to their doctors for preventative things,” he said.

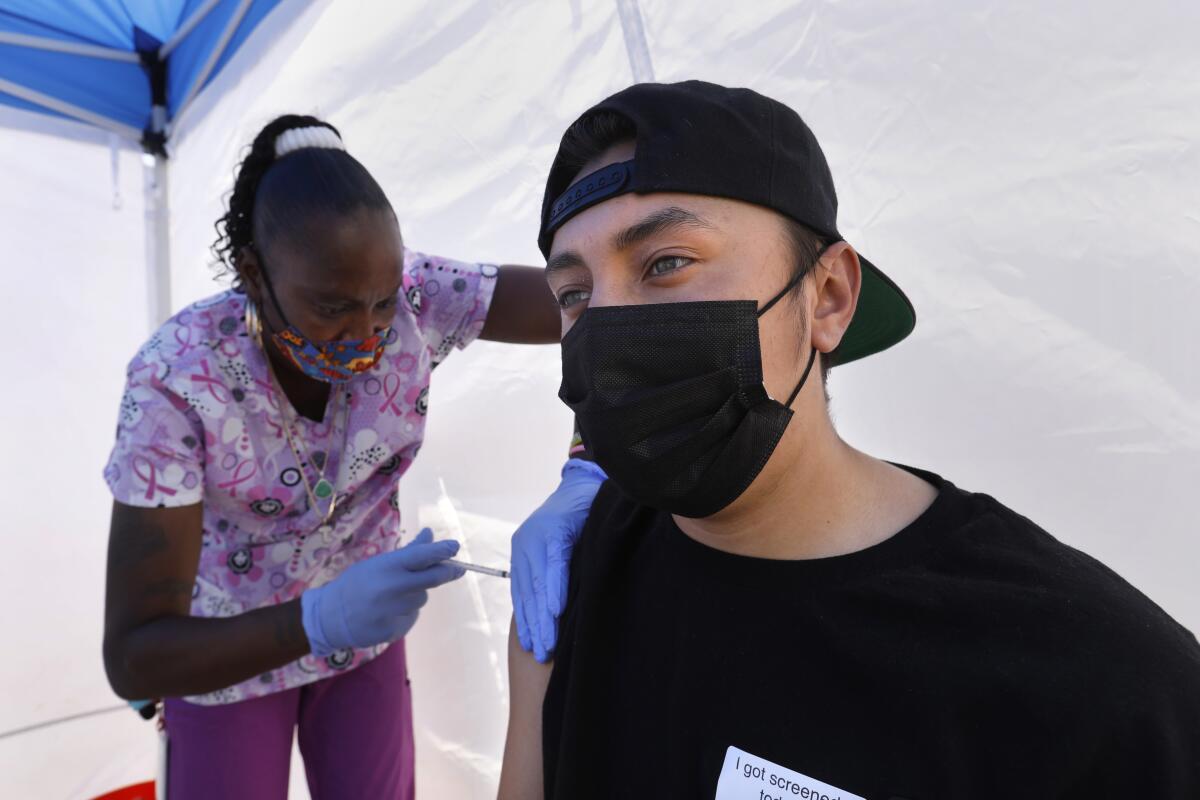

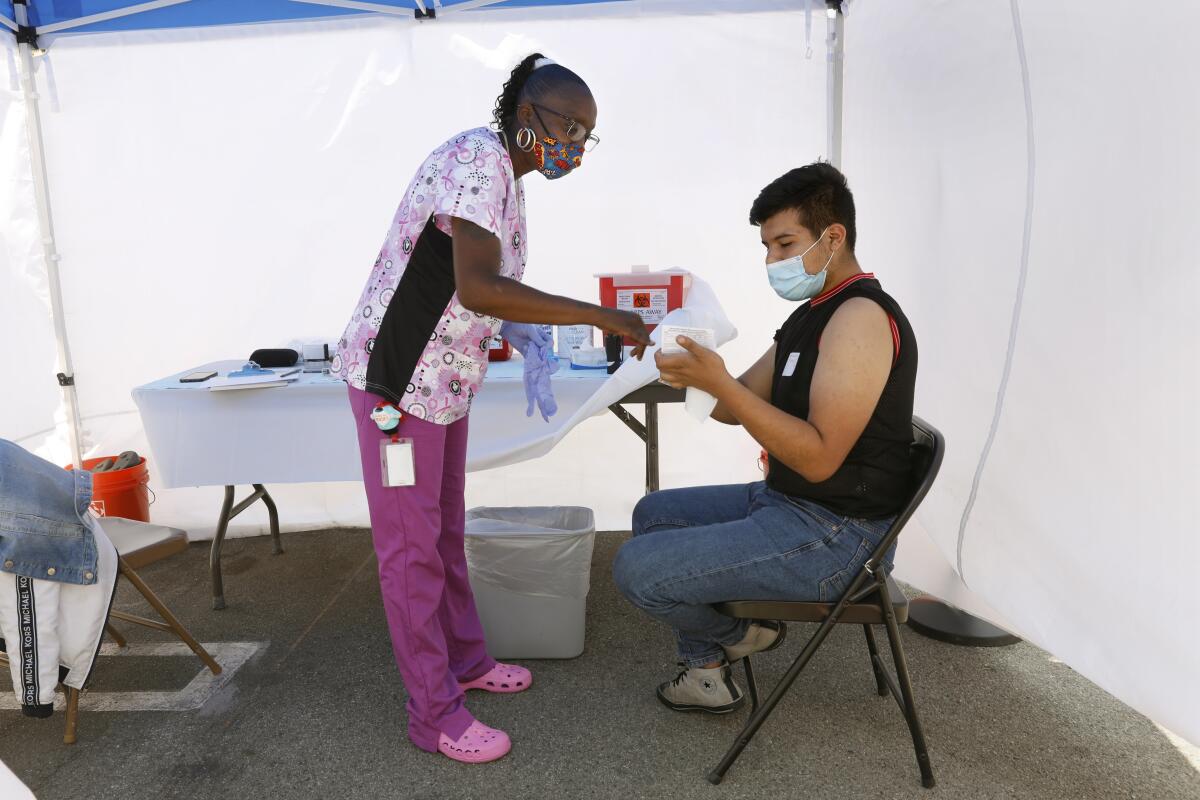

Aura Ortiz, a medical assistant at an East L.A. vaccination clinic, echoed those worries. Far more women than men come in, she said. Many of the men arrive with their wives or families.

It is common for the Latino men to lack health insurance, she said. When she asks about their last doctor’s visit, they say they haven’t gone in two or three years.

That’s a contrast to the white residents she speaks with, most of whom see their doctors regularly and have health insurance even if they don’t have serious conditions.

Ortiz said other factors are misinformation and general distrust of the vaccine due to its fast development.

Latinos have long been targets of inhumane medical policies. Their hard-earned skepticism toward government is now contributing to vaccine resistance.

“They hear all these crazy rumors that aren’t true” — including that the vaccines cause infertility for both sexes, Ortiz said.

Rigoberto Aguiña, a 43-year-old Long Beach resident, said he was unsure about going back for the second vaccine. The first one hurt his arm significantly, and the pain rushed up to his heart. The experience left him scared.

“You don’t know what they’re injecting in your arm,” he said.

Aguiña believes in a conspiracy theory known as the “new world order” — the vaccine was developed by the government to eliminate weak or unproductive people, he said.

Aguiña said he’ll probably go back for his second shot, but only because he thinks his job at a packing company will require it.

Rivera Fernando, also a Long Beach resident, hasn’t gotten his vaccine, but for a different reason.

“I haven’t had time,” he said.

Fernando works at a Chili’s restaurant and hasn’t been able to take time off in two months. He recently booked an appointment — but only because he is due for a regular checkup with his doctor for his diabetes.

You want them to get vaccinated. They don’t. Now what? Tips from experts to have a conversation that could possibly change their mind.

Latino men are often heads of households, working multiple jobs to support their families. They don’t have time to get vaccinated or to vet the information they come across, making them easy targets for rumors circling on social media, Shapiro said.

The main culprits are Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube pages in both Spanish and English filled with conspiracy theories, alarmist news coverage or chismes — gossip — about vaccines causing problems.

“We are all affected by this, but if you’re already suffering and in a vulnerable position, and you’re already having two or three jobs … a lot of the double-checking just doesn’t happen,” he said. “It’s a really bad combination.”

Rodriguez said she can’t be certain what is influencing her husband. His only side effect from the first vaccine was a sore arm.

Everyone around them is pro-vaccine. All Rodriguez’s sisters, cousins and friends are vaccinated, as are her husband’s parents.

The anti-vaccine sentiments seem to be coming from her husband’s peers and his social media, she said. Among these men, there’s a feeling that they can handle it all, that they simply don’t need the vaccine.

“They think they’re macho and can conquer anything and get through stuff on their own,” she said. “You can’t tell them anything.”

She did her best to convince her husband to get his second dose. She urged him to think about their children, who will be at risk if he is only half-vaccinated. But his mind was made up.

“He’s stubborn,” said Rodriguez, who cares for their children full time, including one who is disabled. “I’m not going to argue with him.”

In Vernon, an industrial city with a large number of Latino essential workers, mobile clinics are bringing the vaccine to factories and warehouses.

Vernon rolls out a mobile clinic to give COVID-19 vaccine to essential workers.

At Rose & Shore, a Vernon-based company that makes meals for schools and other agencies, one-third of employees declined to be vaccinated when the mobile clinic visited for the first time, said human resources representative Jacquie Cabrera.

Cabrera estimated that 60% of Rose & Shore’s workers are Latino men. She said many of them feared that the vaccine would impact their preexisting illnesses or conditions.

“Many of them are scared,” Cabrera said. “They’re hesitant because they think it may flare up what they have.”

Jaime Guzman, 44, was one worker who took advantage of the mobile clinic. Guzman said he firmly believes in listening to health experts who spend years studying diseases so they can advise the public.

He has heard many whispers among men who are against the vaccine.

Many have a “machista” attitude or pay too much attention to social media, Guzman said. The biggest rumor he has encountered while speaking to colleagues and friends is that the vaccine affects sexual health.

“I’ve heard from a lot of men that they’re worried it will make them sexually impotent,” he said. “But I’ve always thought, ‘There’s a solution for everything except for death.’”

It takes just a few clicks to find a trove of misinformation on YouTube, he added.

“There’s a lot of videos on YouTube that say the vaccine causes this or that,” he said. “There are a lot of people who aren’t experts uploading comments or videos for the ‘likes.’”

Cabrera said she is working to schedule another mobile clinic at Rose & Shore after a number of employees who first rejected the vaccine changed their minds, possibly because they saw that their vaccinated colleagues had no issues.

In L.A. County, the average number of vaccine doses administered daily has fallen significantly in recent weeks — a sign that many people eager and easily able to be vaccinated have already done so.

Doctors also worried that the lull was a result of distrust after reports that the Johnson & Johnson vaccine may be linked to rare blood clots.

That was the case for Martin Sanchez, 58, who after hearing the reports decided to wait longer to schedule his first appointment. He wanted to see whether anyone around him had a bad reaction.

“I did have doubts,” he said. “J&J made me doubt that vaccine.”

But while he had some reservations, he knew he would have to get the vaccine eventually. A single dad to five daughters, he is pre-diabetic and at increased risk of getting seriously ill with COVID-19.

When he was finally ready last week, he sought out the Pfizer vaccine at the East L.A. vaccination clinic where Ortiz works.

Sanchez, a hotel cafeteria employee, said a few friends and family members tried convincing him not to go. An aunt in his hometown in Mexico told him she read an article about a man who died after getting the vaccine.

After he made up his mind, he stopped paying attention to her. There might be a dozen stories about the benefits of the vaccine, but his family members cling to the one bad one, he said.

“People see the bad stuff and not the benefits,” he said. “I try to pick out the positive.”

Times staff writer Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.