They go one by one, door by door — how a hospital’s ‘promotoras’ are bridging gaps to services

It’s another Thursday morning on Costa Mesa’s Shalimar Drive.

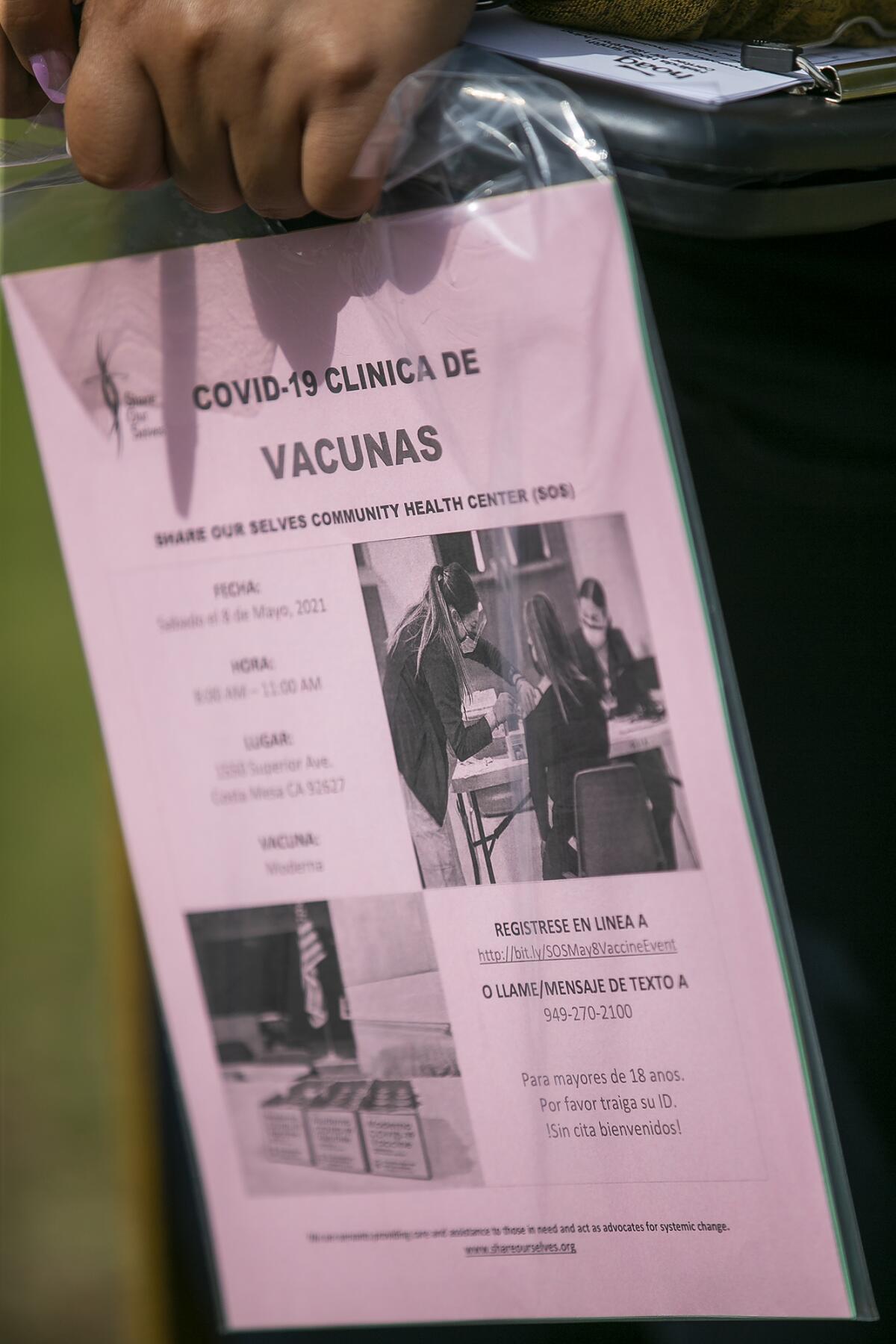

Cars rumble down the road. Distantly, banda music spills out the open windows of a ground-floor apartment. The playground is empty, with all the children having returned to their classrooms. The newest arrivals on the block — this day, at least — clutch clipboards in one hand and a stack of fliers tucked away in clear, plastic bags in the other.

For the record:

11:54 a.m. May 10, 2021Philanthropist Tod White’s name was incorrectly stated as Todd White in a previous version of this story.

It is time to make their morning rounds.

Shoes hit the pavement, and before they even start heading up the staircases of the nearby apartment buildings, before they make their way into the narrow corridors, the group of four approaches passing residents to ask: Have they had the COVID-19 vaccine yet and, if not, do they know where to get it? Do they have any concerns?

This is routine for the “promotoras” of Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian in Newport Beach — bilingual representatives who connect lower-income families with services such as mental health or rental assistance and, more recently, share information on COVID-19 and how to get the vaccines.

The program started about three years ago, said Arturo Diaz, supervisor of the Melinda Hoag Smith Center for Healthy Living.

The center provides mental health services and food distribution and houses nonprofits such as Share Our Selves. It‘s also where the Newport Mesa Family Resource Center is located.

Diaz said the promotoras program is funded by philanthropists Todd and Linda White. Diaz recalled the team was studying the promotoras program for Latino Health Access, a nonprofit in Santa Ana, when the Whites approached the center.

“The Whites asked us, ‘If we were to fund, what would you do with it?’ and [the promotoras program] was the first thing that came to mind, specifically because it’s grassroots,” Diaz said.

“The thought was we have to go out there and make these services accessible to those who don’t know we’re here,” he said. “We have a lot of people coming through here, which is beautiful, but there’s still those people that — either they don’t know about us or they struggle to get in here. Depression will do that to you.

“It can be very difficult sometimes,” he said. “Sometimes, you hear someone knock on your door. Not to sell you anything, but just to check in and say, ‘Hey, how are you all doing and did you know these services were available?’ and you’d be surprised how many people just need that little bit of encouragement. ... How long have they been waiting to have someone to talk to?”

The promotoras at Hoag go into neighborhoods such as Shalimar and the Oak View neighborhood in Huntington Beach to pass along information about services available at the Melinda Hoag Smith Center for Healthy Living and the changing news of the pandemic.

At one point, they brought their laptops around Oak View to get interested people registered for a vaccine appointment.

The team is made up of four outreach workers — Rosalba Lezo, Rocio Matlabalcazar, Bryan Giraldo-Martinez and Santiago Pedraza — in addition to Diaz and the social workers at the center.

Lezo said she and Pedraza try to make it out to the Shalimar neighborhood at least two days a week for eight hours each day.

“We’re talking about a community that didn’t know where to get tested. Was testing available? Did you have to pay for it? As we started getting news, we came out here and it was literally door to door because a lot of misinformation comes through social media. That’s where they were getting [information],” Diaz said.

“We just started coming out here and saying like, ‘Look, this is the most recent information. As we’re getting it, we’re bringing it to you guys. This is where you can get tested. They do not charge here. If you’re getting charged, you need to let us know so we know not to be promoting this place,’” he said.

“But that wouldn’t happen through a phone call. They wouldn’t trust us. We’re just some random person, but because [the promotoras] are already a face in the community, they’re not strangers or not complete strangers,” Diaz continued.

Data show that Latino communities in Orange County have been hit hard by the pandemic, which experts say is because many work in the service sector or are employed in essential jobs.

The health equity quartile positivity rate was introduced in October as a metric determining a county’s tier to ensure disadvantaged neighborhoods did not significantly exceed a county’s overall positivity rate. It is 1.4% in Orange County.

“Right now, we are promoting food distribution, information about the vaccine, the clinics that we have available. Just getting that information to the community, I think is a great opportunity to help those individuals that are underserved,” Lezo said.

Pedraza added, “Sometimes, the lower income people get lost in such an affluent area, so [we’re] just trying to highlight these pockets [where] they’re not getting the resources that they need.”

“Sometimes, I think as professionals, we think we know what people need, but if you’re not out here hearing from them, seeing it for yourself ... it’s kind of out of sight, out of mind,” Diaz said. “But once you’re out here, doing the footwork, you get to see not only the economical needs but the psychosocial impact of poverty.”

Nguyen writes for Times Community News.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.