For USC women, largest-ever sex abuse payout leaves bitterness, vast disparities

Two women, both Asian Americans raised in Southern California, enrolled in USC graduate programs a few years apart. Both went to the student health clinic for gynecological care and both ended up in an exam room with Dr. George Tyndall. Both later said they were sexually assaulted by the doctor, and struggled for years afterward to trust men and medical professionals.

When it came time for USC to compensate them for their injuries, however, their stories diverged sharply. Lucy Chi, a 2014 graduate who works in healthcare information technology, reached a settlement expected to total about $1.2 million. The other alumna, an Orange County mother, was awarded less than $200,000.

“I am sad for my kids,” the second woman said recently through tears. “I made the wrong decision.”

USC’s $1.1 billion settlements to about 17,000 former patients of Tyndall was the largest sex-abuse payout in education history. Behind the jaw-dropping numbers, however, lies a lopsided economic landscape that has left some exuberant and others feeling bruised and cheated.

It is the result of a novel approach USC and its lawyers took to compensate alumnae treated by the gynecologist. A year and a half ago, those former patients had to make a choice between two legal pathways. All were eligible for a federal class-action settlement promoted by USC and several law firms, but they could opt out of the class settlement and gamble on individual lawsuits in state Superior Court. More than 700 women pursued the second option.

It is now clear that from a strictly financial perspective, these risk takers fared significantly better. USC agreed in March to pay $852 million to 710 women with pending lawsuits, resulting in an average payout of more than a million dollars each. The class action settlement prescribed awards of only up to $250,000, depending on an individual’s willingness to share their experience and how settlement administrators assessed the extent of their injuries.

Plaintiffs routinely collect different amounts from the same organization for similar injuries, but experts said the difference in the two groups of Tyndall patients was unusual and surprising.

“I’m really struggling to think of a situation where the highest paid members ... were 10 times higher than a very similar settlement that was reached in the same 12- to 24-month period,” said Loyola Law School professor Adam Zimmerman, who teaches complex litigation and served as counsel to the special master for the Sept. 11 Victim Compensation Fund.

In that case, there were disparities too, but much smaller. The $7-billion fund created by Congress paid an average of $2.1 million to relatives of the deceased. Families who opted out of the fund and pursued individual lawsuits eventually secured settlements that averaged about $5 million.

In the USC cases, some angry class-action participants are now consulting attorneys about potential legal malpractice claims. They feel that, as with Tyndall’s gynecological exams, their lack of expertise put them at a disadvantage. Some said they didn’t understand the legal decision before them; others acknowledged making a strategic error. Most spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“Seeing the headlines ... it just sucks,” said one class-action plaintiff awarded $170,000, adding, “I have nothing against the women who are getting more. I think they deserved that. I just think we also deserve that.”

A similar dynamic could play out at UCLA. The university has agreed to a $73 million class-action settlement to former patients of Dr. James Heaps, an obstetrician and gynecologist accused of assaulting and harassing patients. Those women must decide whether to participate or pursue their own litigation against UCLA by May 6.

USC was inundated with lawsuits after revelations in 2018 that Tyndall, the sole full-time gynecologist at the campus clinic, had been kept on staff despite complaints. Those reports included allegations he had made suggestive remarks about patients’ bodies, asked prurient questions about their sexual histories, targeted Asian women, touched genitals inappropriately and took unnecessary photos during exams.

Tyndall has denied wrongdoing and pleaded not guilty to pending sex crimes charges.

FULL COVERAGE: USC sex abuse scandal

USC retained the prominent law firm Quinn, Emanuel, Urquhart & Sullivan to look for ways to quickly settle as many claims as possible. Sex abuse scandals have proved a reputational and financial nightmare for organizations like the Catholic Church and Boy Scouts of America. Both continue to face wave after wave of lawsuits, leading to uncertain costs and unending headlines that erode the institutions’ standing.

Within weeks of the first Tyndall lawsuit, the Quinn Emanuel lawyers approached attorneys who had filed cases in federal court in hopes of reaching a deal.

These law firms, including San Francisco-based Lieff Cabraser and Seattle-based Hagens Berman, entered into secret negotiations with USC on behalf of not just the clients they had signed up, but all the women who received gynecologic care from Tyndall between 1989 and 2016.

The negotiations in the summer of 2018 were unprecedented in scope, with more than 100 participants crammed into three floors of Quinn Emanuel’s L.A. office. Among them were representatives from 25 university insurance carriers, USC’s in-house lawyers and business staff, several plaintiffs’ firms and a retired judge, Layn Phillips, as mediator.

USC and the firms reached an agreement in October 2018 that would pay all former patients a total of $215 million. Later, Quinn Emanuel would crow in marketing materials that its lawyers “orchestrated” a “novel and unprecedented” settlement.

At the time of the negotiations, prominent universities were paying much larger amounts to sexual abuse victims than provided for under the class action. Michigan State, for example, agreed a few months before talks began to pay $425 million to compensate 332 patients of Dr. Larry Nassar — an average award of about $1.3 million.

For nearly 30 years, the University of Southern California’s student health clinic had one full-time gynecologist: Dr.

USC’s settlement was different in that it included every female patient treated by Tyndall — even those who had favorable experiences or did not remember the appointments at all. The majority would have likely never sued, but wrapping them into the settlement guaranteed they never could.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers, who would receive up to $25 million for fees and costs, told U.S. District Judge Stephen Wilson that the settlement was “not only fair, reasonable and adequate, but an outstanding result.”

Wilson approved the settlement. It was finalized without the class-action attorneys conducting depositions in which USC administrators and other witnesses would have testified about their knowledge of Tyndall’s misconduct. The university’s own internal investigation into Tyndall was still ongoing and its findings were not available for review, though USC did share some records with the law firms.

THE ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION: A USC doctor accused

Chi, the healthcare IT professional, had been a client of Hagens Berman, but she said she had misgivings about the firm even before negotiations started. After she fully understood that she was the only named plaintiff on the initial class-action lawsuit, she switched lawyers and said in an interview that the $215-million agreement undervalued the women’s trauma.

“I feel like they were negotiating on USC’s behalf, instead of the victims’ and survivors’ behalf,” Chi said.

Hagens Berman partner Steve Berman responded that Chi received a copy of the lawsuit before it was filed and the document clearly indicated she was the only plaintiff.

“For sure you can find one or two that now see the payout in the other case and are dissatisfied. But we fully disclosed that possibility to all class members,” Berman said in the email.

Confidential records released this week show decades of warnings to the University of Southern California about Dr.

All former patients were enrolled automatically in the class-action settlement, but anyone could opt out and press a lawsuit in state court. This dynamic created a schism with the university and the class-action lawyers on one side and attorneys ready to pursue state court lawsuits on the other.

Those state court attorneys, caught off guard by the class-action settlement, furiously attacked it as a USC cover-up that would shortchange victims.

“If you are in favor of secrecy about sexual assault and in favor of protecting sexual abusers, this is a great day for you,” Irvine attorney John Manly said hours after the announcement of the class-action settlement.

The lawyers’ ire was partly financial: They stood to gain about one-third of any state court settlements and nothing from the class-action.

University leaders said women should choose the best path for themselves, but they touted the class-action’s benefits. Unlike in individual lawsuits, the settlement was completely private. No one would have to testify in open court.

The settlement also offered the certainty of a financial award, with different tiers of payments depending on how much each woman wanted to participate. If a woman did nothing, she would receive $2,500. If she agreed to a confidential interview describing Tyndall’s impact on her life, she would get up to $250,000. On the other hand, if the women sued, there was no guarantee of money. Their cases might be thrown out or rejected by juries.

RELATED: Secret warnings of abuse at USC

USC and the class-action lawyers also pointed to nonmonetary provisions in the settlement that aimed to reform university culture: USC had to hire a women’s health advocate, perform enhanced background checks for staff, and institute a new sexual misconduct prevention program for students.

“People who have been victims of sexual misconduct and abuse, one of the things they want more than anything is for this to not happen to anyone else,” said Charol Shakeshaft, an educational researcher appointed the women’s health advocate.

Women had about a year to decide which route to choose. For many, the class-action’s expediency was attractive.

“I didn’t want it to become my life,” said one class-action plaintiff who was later awarded $30,000. Her 2013 experience with Tyndall was unpleasant, she said, but had little long-term impact on her. “If my experience had been more extensive ... yeah, I would have joined the lawsuit, but I feel like I was fortunately on the outskirts of what happened.”

Claire Cahoon, an attorney who received her undergraduate degree from USC in 2017, said the class-action was “a no-brainer” for her because it was “more streamlined” and wouldn’t require her to submit to adversarial questioning.

“I didn’t want it to be about me. I wanted it to be about him and about USC,” Cahoon said. She declined to say the amount of her award, but described it as “significant” and more than she expected. Even after learning about the massive state court settlement, she said, she had no regrets. “It made me really happy for those women,” she added.

Those who now regret staying in the class-action offered various explanations for the decision they now second-guess. The Orange County mother said she “fell for a rumor” that USC’s insurer was going to go bankrupt if the settlement went above the $215 million set aside for the class-action.

Another alumna ultimately awarded $150,000 said that as the first in her family to attend college, she knew few people with the legal savvy to advise her. She thought only a handful of women would take the step of filing suit, not the hundreds who ultimately did.

“I didn’t realize,” she said. “It wasn’t that I was scared to go to court or face Dr. Tyndall, I would have done that.”

On Monday, the Los Angeles Times won the Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting for articles that exposed Dr.

Another said she was unfamiliar with a proper gynecology exam and initially thought her experience was probably not bad enough to merit a suit. During the class-action interview, she began to understand how Tyndall had violated her.

“Someone in this situation took advantage of my lack of knowledge and having that happen again when that is exactly what he did to all of us — take advantage of our not knowing — does not feel like justice at all,” said the woman, who was awarded $170,000.

Annika Martin, one of the lead attorneys for the class-action, said the feedback on the settlement from former patients had been “overwhelmingly positive.”

“Obviously I’m sorry to hear that anyone is unhappy,” Martin said. She rejected the idea that the class-action participants did not have enough information or legal acumen to choose wisely.

“All of these women are intelligent, educated women who are more than capable of making the right decision and informed choices based on the personal reasons that are right for them,” Martin said in an interview.

She said it was unfair to judge the settlements by the payouts alone since the class-action deal delivered privacy, certainty and campus reform, adding, “It is not the apples to apples comparison that your question seems to be presenting.”

Shon Morgan, a Quinn Emanuel partner who led USC’s defense, said it was logical that women who took USC to court on their own ended up with higher payouts.

“I would suspect that the people who tended toward the individual litigation were the group who had the most unfavorable experience with Dr. Tyndall and therefore it is not unexpected you would see higher awards to that group,” Morgan said.

What is clear is that USC’s lawyers believed the class-action settlement was a prudent financial move for the university. Morgan’s law firm biography now boasts that the settlement resolved “the class actions at a small fraction of the per-plaintiff amount that other institutions have paid in similar cases.”

The state court cases against USC took just under three years to resolve. About 15 women were deposed as were USC administrators and one trustee. There were rounds of settlement negotiations and it wasn’t until March 25 that the sides announced the $852 million price tag, which brought USC’s total bill to a record-setting $1.1 billion.

At least a third of the state court settlement — approximately $300 million — is expected to go into the pockets of plaintiff’s attorneys. By contrast, USC will pay the plaintiffs’ legal fees and costs in the class action and they cannot exceed $25 million.

Though lawyers for the state court cases had criticized the lack of transparency in the class action, their settlement does not require USC to make public internal files or deposition transcripts, which remain confidential.

RELATED: How years of alleged sex abuse was uncovered at USC

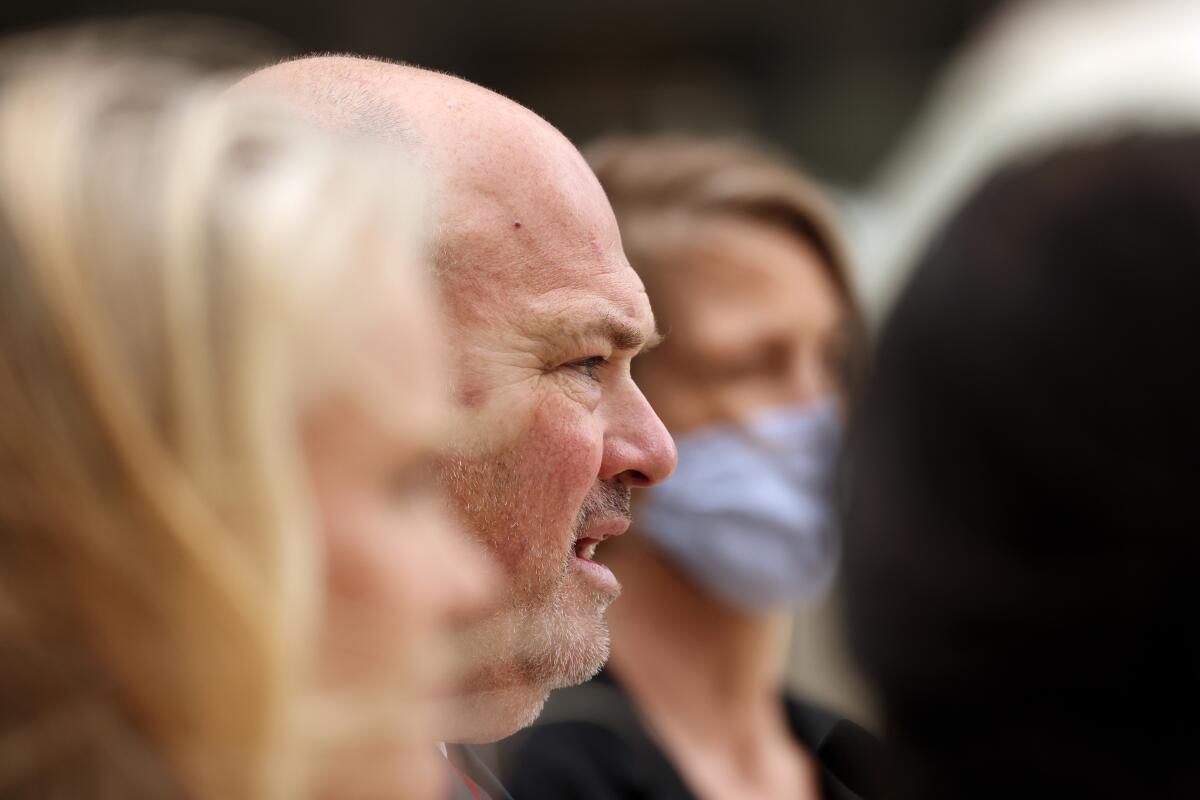

In a recent interview, USC trustees Chair Rick Caruso praised the class-action settlement as an important option for women who wanted an “easier, less impactful” way to secure recompense.

“The decision we made was the right decision to give people a path to be compensated,” Caruso said.

In an apparent coincidence, many of the women in the class action settlement learned the amount of their individual payout in the week after news broke of USC’s state court settlement. The average for women who participated in the highest tier was $96,000 — less than a tenth of the state court average.

Dolores Leal, a partner at Allred, Maroko & Goldberg who represented 72 patients in individual lawsuits, said she has received many calls from unhappy class-action plaintiffs. Some said their attorneys did not inform them of the 2019 law that temporarily lifted the statute of limitations for sex abuse cases so that people with dated claims could sue.

“A lot of these women decided to pursue the class action because they thought they wouldn’t get anything and their case would be thrown out,” said Leal.

Leal and other attorneys are interviewing prospective clients about a potential legal malpractice claim against the class-action lawyers.

Martin, the class-action lawyer, said a website for Tyndall’s former patients was updated to reflect the change to the statute of limitations and that some class participants had even lobbied for the legal change. She also said that USC alums were besieged with advertising by lawyers seeking to take on individual lawsuits after the statute of limitations changed.

The Orange County mother said she had coped with trauma over Tyndall by focusing on what the eventual financial award would do for her young children. “You think to yourself maybe this will pay for my kids’ college,” she said. Now, racked with regret, she said, “One thing I had been hoping for is to get closure, and what I don’t have is closure.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.