Most states have a system for ousting bad cops. In California, legislation is struggling

SACRAMENTO — Despite weeks of street protests over the killing of George Floyd and California’s reputation for progressive politics, a series of major police reforms proposed in Sacramento largely fizzled in 2020.

Backers hoped to have more success in 2021, with the pandemic waning, legislators spending more time on the issue and momentum building to address inequities in policing.

But police reform is hitting hard times again this year, including a plan common in other states to oust bad cops.

Across the nation, 46 states have rules preventing abusive officers from jumping jobs, furthering their careers by switching agencies even after they’ve committed serious misconduct or been fired. California is not one of them — but a proposed law to change that is facing unexpectedly fierce opposition at the Capitol.

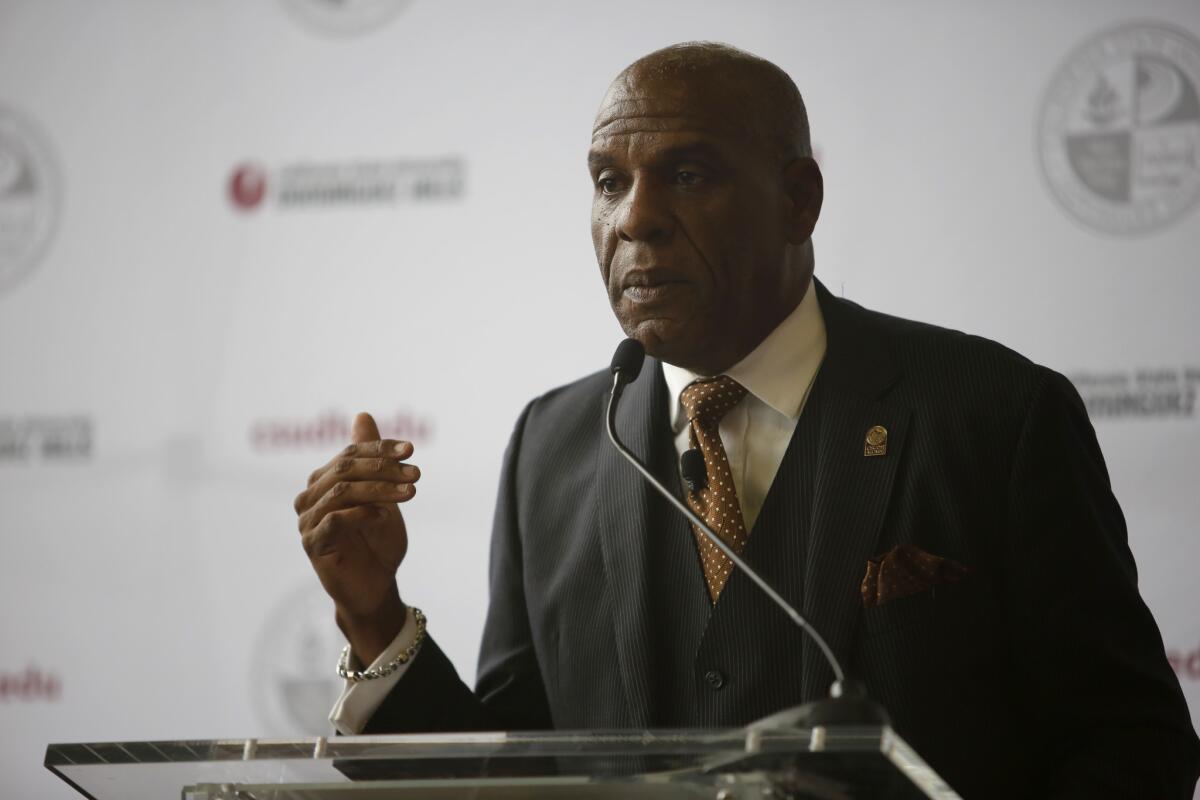

For seven tense hours Tuesday — one week after a former Minneapolis police officer was convicted of murdering Floyd — legislation to ban peace officers found to have acted with significant malfeasance in California seemed on the verge of dying in the Senate Judiciary Committee. The bill’s author, a Black man representing Gardena, had to promise to compromise on key provisions to keep it alive, even as he vented about the pushback he met on one of the proposal’s first steps through the legislative process.

“If not now, when?” Sen. Steven Bradford asked the committee, his frustration evident. “This is a tough issue, but it’s a righteous issue…. It’s better than what we have, and it surely beats nothing.”

Currently, only Hawaii, New Jersey, Rhode Island and California do not have centralized systems allowing state officials to revoke an officer’s right to work in law enforcement if they are found to have violated set standards, similar to licensing rules for doctors, barbers or acupuncturists. California had that ability in a more limited fashion until a 2003 law pushed by sheriffs and signed by Gov. Gray Davis ended it.

It is the only state to have ever revoked its own oversight right, said Roger Goldman, a professor emeritus at St. Louis University who studies law enforcement decertification.

Bradford’s pledge to work with critics allowed his proposal to clear the committee but left uncertain how the bill will change. The intense brawl with fellow lawmakers — who attempted to waylay the measure despite its co-author being the powerful Senate president pro tem, Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) — brings into question whether it will be watered down or can become law at all.

Despite years of efforts, police reforms remain difficult to pass at a state Capitol in which moderate and progressive Democrats are often divided and law enforcement unions remain powerful.

Senate Bill 2 is also a dense proposal that covers more than licensing, opening the door for the kind of nuanced debates that can leave even legislators confused, and it contains details with significant real-world consequences.

Along with the licensing, it seeks to reform the Tom Bane Civil Rights Act, a measure passed in 1987 and originally crafted to address hate crimes. Those changes would make it easier to bring civil rights lawsuits against police in state court, where they do not have the same qualified immunity, a legal shield that protects government officials from being held personally liable for constitutional violations in federal cases.

California courts have weighed in on the Bane Act numerous times over the decades, morphing its original perimeters in ways that both plaintiffs’ and defendants’ lawyers have lamented. Multiple legislators and advocates agreed Tuesday that it is a “hot mess” that lacks clarity and has strayed far from its original intent. But it was proposed fixes to the Bane Act that led to the bill’s near demise.

Critics of the Bane Act changes argued that the proposed language creates more confusion, a problem that could send more cases of police misconduct to state courts while also leaving judges to interpret what legislators meant. Supporters of the bill say those concerns are cover for backing away from reforms unpopular with police.

One key issue is how juries should determine whether an officer had the intent to violate civil rights. To be found liable for civil rights abuse under current interpretations of the law, an officer must not only have committed a physical act of coercion, threat or intimidation — such as firing a gun or withholding medical care — but also have meant to violate constitutional rights while doing it. Critics of that “specific intent” standard say it’s too high a bar and one that was never meant to exist.

Bills moving forward in the state Legislature were applauded by an array of civil rights and police reform groups.

It stems from a controversial 2017 court decision in an unusual case in which police arrested a fellow officer after observing what they thought was suspicious activity — he was jogging in a San Francisco park while wearing long pants. The unfounded arrest caused the officer to lose his job. The court awarded the fired peace officer $575,000 under the Bane Act. But in an attempt to clarify the law, the judge created the “specific intent” rule.

“What the court did was surprising,” said Michael Haddad, the attorney in that case and a proponent of SB 2. “Unfortunately many judges now expect us to have proof of what the officer was actually thinking.”

Instead, Bradford and advocates have suggested returning to pre-2017 standards — meaning that the act of committing the violation would be enough to prove a “general intent” to ignore civil rights. Such a shift would bring state law more in line with federal standards, but some worry it only re-creates the ambiguity the court sought to fix with the San Francisco decision.

SB 2 would also open the door for wrongful death suits to be brought under the Bane Act — they are currently not allowed because of a 1995 court ruling that excludes fatal claims. Because state laws on deadly force are stricter than federal standards, some attorneys say a wrongful death claim under the Bane Act would be easier to prove and provide an important path not just for justice, but information.

“What is important here is really accountability, particularly for somebody whose family member has been killed by police,” said American Civil Liberties Union attorney Peter Bibring. “Too often the D.A.’s investigation doesn’t lead to any accountability and more importantly doesn’t lead to real answers for the family.”

But lawyers for police unions argue current state laws work fine for wrongful-death claims, allowing them to be filed as regular lawsuits without the Bane Act.

They say the lower standard would open a floodgate for claims and is a ploy by consumer attorneys to win higher fees. Wrongful-death claims won under the Bane Act can qualify for “fee multipliers,” meaning attorneys can receive double, triple or even more of their actual fees. Those bills, potentially millions, probably would be paid by the municipalities that employ officers, said David Mastagni, a lawyer who represents police and law enforcement unions.

Julia Yoo, board member of the Consumer Attorneys of California, which supports the bill, countered that the fee provisions give lawyers incentive to take on important civil rights cases even when the client may not be able to pay. “The vast majority of these civil rights cases are brought by victims who come from poor, Black and brown neighborhoods and who may not have the means to pursue justice on their own,” she said.

Though the Bane Act took center stage Tuesday, SB 2’s toughest challenge may revolve around banning officers. Law enforcement unions are adamant that those provisions are unfair and may run afoul of rights guaranteed by contracts and law. Multiple law enforcement organizations and chiefs of police called in during testimony said they supported a decertification process but not the one suggested by SB 2.

Despite weeks of rhetoric and numerous proposals, California ended its legislative session with only a handful of moderate police reforms. Here’s why.

Law enforcement is especially unhappy with a proposed state board that would advise on misconduct decisions and have investigative power. They argue it’s unclear what conduct could lead to a ban and take issue with the board being comprised mostly of advocates and those affected by police violence.

“The current makeup of the board is akin to appointing anti-vaxxers to a committee that would approve vaccines,” said Tom Saggau, a spokesman for police unions in Los Angeles, San Jose and San Francisco. Mastagni, the lawyer who represents law enforcement, added that the board’s ability to recommend a ban even if a peace officer’s employer or courts find them innocent is troubling and may violate due process rules.

Supporters of the reforms say civilian oversight is needed to restore faith in policing. They point out that internal affairs investigations are often conducted in secret, making it nearly impossible to know how and why officers are exonerated or disciplined, and criminal charges for peace officers remain rare.

Bibring, the ACLU attorney, said California regulates more than 200 other professions and sanctions misconduct in almost all of them regardless of whether an employer believes it is warranted. “That is the whole point of a licensing scheme,” he said.

With months and multiple votes ahead before the measure could make it to the governor’s desk, Bradford said the fight is “far from over.” The bill will next go to the appropriations committee, where the cost of implementing an oversight system will be discussed.

“I just know the nature of this business,” he said. “I know the dance.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.