The day after Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs was found dead in his hotel room, Eric Kay, the team’s longtime communications director, leaned against a blue cinder block wall during a news conference at Globe Life Park in Arlington, Texas.

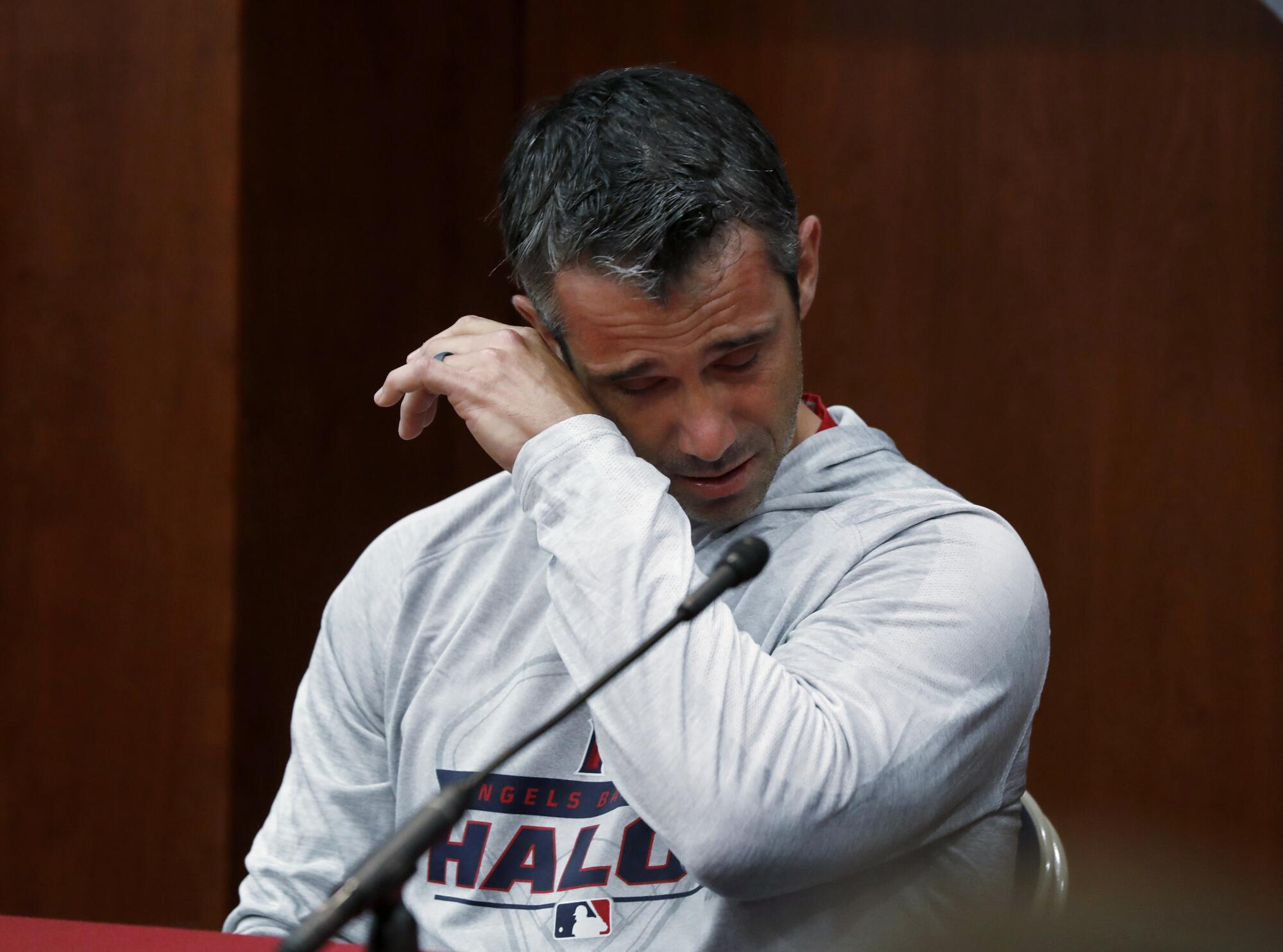

A few feet away, facing cameras and reporters, manager Brad Ausmus wiped away tears as he described how the Angels coped during the previous 24 hours.

Sadness and shock over the unexpected death of the popular player from Santa Monica hung over the stadium on the warm afternoon in July 2019. Little was known about the circumstances of the death. Questions abounded. How could a seemingly healthy 27-year-old professional athlete die with no obvious explanation?

Kay shifted weight from one leg to the other. His left hand clasped his right wrist. He took a deep breath, leaned back, looked at the ceiling, then slowly exhaled. He appeared as dazed and heartbroken as everyone else in the room.

Authorities allege Kay knew more than he let on at the time.

Almost two years later, the now-former Angels employee is scheduled for trial this summer in U.S. District Court in Fort Worth. Kay, 46, is charged with giving Skaggs counterfeit oxycodone pills laced with fentanyl that resulted in his death, and with conspiring since at least 2017 to “possess with the intent to distribute” a substance containing fentanyl. The Tarrant County medical examiner ruled that Skaggs died from “mixed ethanol, fentanyl and oxycodone intoxication” that led to choking on his vomit.

Kay, the only person to be charged, has pleaded not guilty.

The overdose turned Skaggs’ wife into a widow, robbed professional baseball of a rising star, brought the sport face to face with the country’s opioid epidemic and sparked a wide-ranging investigation by local police and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Though authorities remain tight-lipped about the probe, court filings, text messages, law enforcement records and interviews provide a fuller picture about events leading up to Skaggs’ death and the investigation that’s still active. The main focus has been the relationship between the pitcher and the communications director.

::

At first glance, the two men couldn’t have appeared to be more different. With his receding hair and stout build, Kay resembled another middle-aged father from the suburbs; Skaggs had the lanky frame and powerful left arm that seemed to have him destined for baseball greatness from a young age.

The pitcher starred at Santa Monica High and remained close with a tightknit group of friends from the area. Among a sea of tattoos on his right arm was an outline of California with the 310 area code inside. Skaggs didn’t take himself too seriously, always appeared upbeat, worked out ferociously, brought energy to wherever he was. “He didn’t make anyone feel like he’s better than you, even though he was,” one close friend said.

The Angels drafted Skaggs in the first round in 2009. He took a circuitous path to the majors, with the Angels trading and later reacquiring him. After a 19-month recovery from surgery for a torn ligament in his left elbow, he established himself as a regular in the starting rotation.

Kay was a familiar presence around the Angels, having worked in the communications department since 1996. He had been the director of communications for six years, developing a reputation among journalists as friendly and nonconfrontational, someone quick to crack one-liners, roll with the ribbing that’s commonplace in clubhouses, and to show off pictures of his three boys. He seemed eager to please, providing a heads-up when news was about to break and once offering to allow a journalist’s children to watch batting practice and meet Angels stars Mike Trout and Shohei Ohtani.

People around the Angels didn’t think Kay and Skaggs had a particularly close relationship — Kay wasn’t among the guests at Skaggs’ wedding in December 2018 — or anything more than routine interactions.

A Texas grand jury has been hearing evidence that could form the basis for criminal charges related to the opioid overdose death of Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs.

The two men spoke on the phone June 26, 2019, at 10:57 a.m. It’s the only call between the two during that month listed in Skaggs’ phone records in his family’s possession. The conversation lasted about two minutes, though the subject isn’t known.

Three days after the call, Skaggs threw 91 pitches over 4-1/3 innings against the Oakland Athletics at Angel Stadium. The left-hander wasn’t as sharp as usual. His final pitch was a curveball that Marcus Semien laced into deep left-center field for a double.

The morning after, June 30, while still in California, Skaggs texted Kay, according to a person familiar with the exchange. The pitcher wanted something for pain. He had spent time on the injured list in April for a sprained ankle, but whether he sought painkillers because of that injury or for another reason isn’t publicly known.

At 2:35 p.m., while the Angels played the Athletics in the final game of their series, Kay responded: “Hoe [sic] many?”

The exchange, retrieved from Skaggs’ phone by investigators, is detailed in a charging document.

“Just a few like 5,” Skaggs texted back a minute later.

“Word,” Kay wrote.

“Don’t need many,” Skaggs added.

After the game ended, the Angels showered and changed into Western-themed outfits for their trip to Texas. Skaggs had suggested it. The team bused to Long Beach Airport and posed for a picture in front of their chartered United Airlines 757. Skaggs stood out among the would-be cowboys. He wore an enormous black hat, black shirt embroidered with pink and blue flowers, and black jeans.

Authorities obtained location data for Kay’s phone, which first showed it at the Hilton Town Square in Southlake, Texas, the team hotel for the four-game series against the Texas Rangers, at 11:15 p.m.

Twenty-three minutes later, hotel records showed Skaggs used his key card to open the door to his fourth-floor room.

He messaged Kay the room number “469” and “Come by” at 11:47 p.m.

“K,” the communications director responded at 11:50 p.m.

Geoffrey Lindenberg, the DEA special agent who signed the affidavit supporting the criminal complaint against Kay, said in the document, “I believe [Skaggs] and Kay were discussing drugs, specifically in this case, blue 30-milligram oxycodone pills.”

The affidavit doesn’t explain why Lindenberg believed the texts referred to drugs.

Around midnight, Carli Skaggs sent her husband a good-night text as was their custom during road trips. He didn’t respond.

::

The next afternoon, about five hours before the Angels were scheduled to play the Rangers, an emergency dispatcher’s voice came on the radio in Southlake at 2:17 p.m.

“Medic 4-1, truck 4-1 respond,” the dispatcher said. “Medical emergency, Hilton Southlake Town Square.”

They updated the call: “It’s gonna be … a possible death investigation. PD is arriving on scene now.”

Authorities discovered Skaggs on his bed. He still wore the cowboy outfit. There weren’t any signs of trauma.

Southlake police investigators found a blue pill stamped with “M/30” in the room — the standard mark for a 30-milligram oxycodone pill — and white powder on the floor. Both later tested positive for fentanyl, which is a stronger opioid than oxycodone and often used in counterfeit oxycodone pills. A person familiar with the case said Skaggs is believed to have crushed a pill with his hotel room key cards and snorted it.

Investigators also said they found “several white pills” that were identified as anti-inflammatories and five pink pills imprinted with “K56.” They were later determined by a laboratory test to be legitimate 5-milligram oxycodone pills. Skaggs’ family isn’t aware of any prescription he had for the drug. Court filings don’t indicate the source of those pills, though Lindenberg’s affidavit said they didn’t come from Kay.

When investigators interviewed Kay that afternoon, he told them Skaggs had been drinking on the flight to Texas and the last time he saw the pitcher was when they checked into the hotel.

“Kay stated that he was unsure if [Skaggs] was a drug user,” Lindenberg’s affidavit said, “except for possibly marijuana.”

::

Eleven days later, July 12, the Angels played their first game in Anaheim since Skaggs had died. He would’ve turned 28 the next day. His mother, Debbie, threw out the first pitch. The Angels all wore red jerseys with Skaggs’ name and No. 45 on the back, then two pitchers combined to hold the Seattle Mariners hitless.

“Of course a no-no,” Kay tweeted.

Afterward, players put the game ball in Skaggs’ locker.

Ten former USC Song Girls described to The Times a toxic culture within the famed collegiate dance team that included longtime former coach Lori Nelson rebuking women publicly for their eating habits, personal appearance and sex lives.

In mid-July, according to Lindenberg’s affidavit, Kay told an unnamed person that he had visited Skaggs’ room the night of the death after getting a text message from the pitcher.

The affidavit alleged that “several individuals” who weren’t named knew that Kay gave pills to Skaggs.

“These individuals confirmed that Kay would provide 30-milligram oxycodone pills to [Skaggs] and that at times, Kay, [Skaggs], and others would refer to these pills as ‘blues’ or ‘blue boys’ because they were blue in color,” the affidavit said. “I also learned that Kay would distribute these pills to [Skaggs] and others in their place of employment and while they were working.”

::

The Tarrant County medical examiner released the autopsy report for Skaggs on Aug. 30, 2019, determining the death to be an accident. The presence of opioids drew national attention. In a statement the same day, his family added to the furor with a statement saying they were “shocked” to learn from authorities that an unnamed Angels employee might have been involved in the death.

A dozen or so Angels players and a few broadcasters were on the 3 p.m. bus about to depart the Hilton hotel in Southlake, Texas, for Globe Life Park on Monday when traveling secretary Tom Taylor delivered the devastating news.

The Angels hired Ariel Neuman, a former federal prosecutor in Los Angeles, to conduct an “independent internal investigation” of the circumstances leading to Skaggs’ death.

“Our investigation confirmed that no one in management was aware, or informed, of any employee providing opioids to any player,” an Angels spokeswoman said in a recent statement. “We continue to feel the loss of Tyler and are committed to working with the authorities as they complete their investigation.”

While authorities explored the circumstances surrounding Skaggs’ death, the difficulties grew for Kay’s family. In mid-July 2019, a month and a half before the release of the autopsy report, police responded to Kay’s home in Orange for what the call log described as an “overdose.” On Oct. 5, police responded to Kay’s home again, this time for a “domestic family disturbance.” The Orange Police Department said no incident reports were written for the calls. But Oct. 5 is listed on a divorce petition filed last year by Kay’s wife, Camela, as the date the couple separated.

“The current cohabitation arrangement is untenable and unhealthy,” Camela Kay wrote in the petition in Orange County Superior Court. “The Respondent is struggling with a number of serious issues, causing him to be unkind toward me, our minor child, our two adult children, and Respondent’s mother (all of whom live in the home).”

William Reagan Wynn, Eric Kay’s Fort Worth-based attorney, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Later in October 2019, ESPN reported that Kay told DEA agents he struggled with opioid addiction, provided oxycodone to Skaggs for years and was in the room in Texas when the pitcher snorted the crushed opioid. Kay alleged Angels executives knew about the drug use; the team emphatically denied the claim.

Kay’s LinkedIn page showed his employment with the Angels ending that November.

“I just know that attempts to blame any one person for another person’s addiction are extremely naïve,” Michael Molfetta, Kay’s Newport Beach-based attorney, told The Times after the story. “I think any attempts to blame Eric Kay for what happened are shortsighted and misguided. When all the facts come out, I think that what happened is a tragedy…. But to say it’s any one person’s fault is not right.”

The investigation moved forward, though largely out of public view.

In December 2019, almost six months after Skaggs died, authorities searched Kay’s Angel Stadium office, according to a person familiar with the matter. The DEA’s South Central Laboratory in Dallas subsequently analyzed several exhibits connected to the case. They included a sunglasses case, “commingled razor blade holder, razor blade and sleeve” and a “small, metal cylinder with a screw cap.” The last two items, which came from the office, according to a court document, contained “powder residue” that a forensic chemist working for the DEA “conclusively identified.” The substances weren’t named.

The family cleaned out Skaggs’ locker at Angel Stadium in late January 2020, another person familiar with what happened said, after being delayed because law enforcement wanted to examine the contents.

On Aug. 7, Kay turned himself in to federal authorities in Fort Worth, and the criminal complaint against him was unsealed. Lindenberg’s affidavit alleged that Kay and Skaggs “had a history of narcotic transactions, including several exchanges wherein Kay acquired oxycodone pills for [Skaggs] and others from Kay’s source(s) and distributed these pills to [Skaggs] and others.” It added: “Kay had multiple contacts with some of these source(s) in the days leading up to and surrounding [Skaggs’] overdose death.”

But a one-sentence allegation in the affidavit might have been the most important: “It was later determined that but for the fentanyl in [Skaggs’] system, [Skaggs] would not have died.”

Almost 50,000 people died of opioid-related overdoses in 2019, according to government figures, accounting for the bulk of the 70,000 drug overdose deaths recorded during the period. Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that’s 80 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, played a key role. In Los Angeles, for example, the DEA’s seizures of counterfeit oxycodone pills laced with fentanyl ballooned from 120,000 pills in 2017 to 1.2 million in 2020. Fentanyl is linked to about half of the drug-related deaths in L.A. County.

Kay’s attorneys issued a statement the same day as the arrest, saying their client will “wait patiently for his opportunity to make his story known.”

At a news conference in Fort Worth, then-U.S. Atty. Erin Nealy Cox said: “It should prove to his many, many fans that no one is immune from the deadly addictive nature of these drugs, whether sold as a powder or hidden inside an innocuous-looking tablet. Anyone can be fooled by counterfeit prescription drugs.”

She added, “This investigation remains open and active.”

::

The same month, DEA agents executed a search warrant at a modest home on the corner of a sleepy street in Corona, according to law enforcement records. A former longtime, low-level Angels employee lives there.

Asked about the warrant, a DEA spokeswoman said, “This is an ongoing investigation so we can’t comment at this time.”

The ex-employee didn’t return numerous messages seeking comment. Thomas Tears, an attorney representing the former employee, said, “He hasn’t done anything wrong,” and the DEA is “just looking at things, but [he] is not involved.”

In another court filing, prosecutors said that one of their experts, FBI special agent Mark Sedwick, will testify about his review of “GPS coordinates extracted from cellular telephone provider records.” Two numbers were mentioned. One belonged to Kay. The other number was linked in 2019 to an Orange County resident unaffiliated with the Angels who has numerous prior criminal convictions, including possession of a controlled substance, identity theft, burglary and grand theft.

Kay’s trial has been repeatedly delayed, including because one of his attorneys contracted COVID-19. The trial is now scheduled to start Aug. 16. Among the cache of evidence are 24,000 pages of records — including from law enforcement, telephones, finances and medical care — plus 185 gigabytes of email files. The evidence also includes interviews with witnesses who are “professional athletes and/or otherwise affiliated with Major League Baseball in various capacities,” and “sensitive information related to other investigations.”

Rusty Hardin, the high-profile Houston attorney representing the Skaggs family, said through a spokesman that they haven’t decided whether to pursue a lawsuit relating to the death.

The Southlake Police Department, the agency that started the investigation, declined to discuss the probe into Skaggs’ overdose. A spokesman said, “This is still an active DEA case.”

Times staff writer Mike DiGiovanna contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.