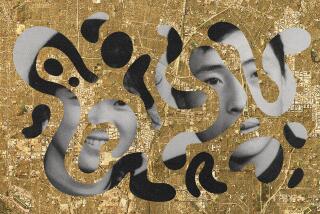

Not all Asian Americans are being vaccinated at high rates. A Chinatown clinic shows why

COVID vaccination pop-up serves seniors in Chinatown

Before the pandemic, Sissy Trinh ran after-school programs as founder and executive director of the Chinatown-based youth organization Southeast Asian Community Alliance.

But since last year, the organization of five people pivoted to COVID-19 relief, delivering food and other resources to vulnerable residents in Chinatown and Lincoln Heights.

For the record:

10:34 p.m. April 21, 2021A previous version of this article gave incorrect demographic and median income data for Chinatown in 2019. The area is more than 50% Asian, and the most recent median income levels available are from 2013. The article incorrectly said SEACA works with people who speak Korean. Languages the group works in include Cantonese, Toisanese, Vietnamese, Tagalog and Spanish. The article also incorrectly identified Cevadne Lee as a physician. She is a public health expert and the director of community engagement and outreach at the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

She soon realized that existing government programs weren’t accessible to the families her group served: those with language and technology barriers.

“I’ve been harassing the mayor’s office since [last] April,” she said. “‘You need to come out to Chinatown. We need support.’”

In February of this year, the city was in Chinatown, vaccinating nearly 1,000 residents. But getting that many people to the pop-up clinic took determination and hard work from a variety of groups.

Why Chinatown?

Chinatown’s population is more than 50% Asian, according to 2019 Census data. L.A. County is about 14% Asian. A 2013 report by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, the most recent detailed data available, showed that the median income in Chinatown by household was $19,500 a year, making it one of the poorest neighborhoods of Los Angeles at the time. The median income of Asian residents in Chinatown was lower: $17,000.

“We have students who think that $25,000 for a family is middle class,” Trinh said. “They aspire to that because so many of their families work in sweatshops, restaurants, under the table, where they’re not getting paid the minimum wage, right? So that’s who we serve. ... The people who are struggling to pay rent, who are one rent increase away from becoming homeless.”

Baldwin Park had the second highest rate of COVID-19 deaths in the San Gabriel Valley, yet it lagged in vaccinations. Here’s how a church and various other groups set up a clinic

The families SEACA works with speak Cantonese, Toisanese, Vietnamese, Tagalog and Spanish. Many of them don’t have cars, and many have members who live in senior housing complexes.

Those complexes can make avoiding the coronavirus difficult. “That’s 20 people who share a bathroom, share a kitchen, so even if you’re isolated in your room, you’re still at risk of exposure,” Trinh said.

When the vaccines became available, she and fellow community leaders — including Jack Cheng, director of operations of the Chinatown Service Center, which has medical clinics in Chinatown and San Gabriel, and Cevadne Lee, a director of community outreach and engagement at UC Irvine’s Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center who works on Asian American health equity efforts in L.A. and Orange counties — quickly realized there were efforts in place by the government to target Latino, Black and Native American communities.

But Asian Americans generally have not been seen as an underserved community.

According to data released by the L.A. County Department of Public Health in early February, Black, Latino and Native American seniors in Los Angeles County were receiving COVID-19 vaccinations at a lower rate than white, Asian American and Pacific Islander seniors. As of April 4, the data showed that 22.7% of Black and Latino county residents age 16 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, compared with 40.4% of Asian residents, 38.1% of American Indian/Alaska native residents and 37.1% of white residents.

But many Asian American community organizers and medical workers believe the data is not telling the full story.

“We at one point had 3,000 individuals on our [vaccine] waitlist, and we only got a weekly allocation of 200 [doses],” Cheng said.

That was too slow.

“Watching the system and how it was initially rolled out, and seeing the vaccine chasers and all this other stuff, we kept thinking, ‘This isn’t working for our communities, and people are going to continue to die,” said Trinh.

“We’re in the shadow of the largest testing and vaccination site in the country,” she added, referring to Dodger Stadium. “And yet none of the seniors are able to get there.”

So UCI’s Lee, who is part of the AANHPI Health Initiative, a coalition led by Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council (A3PCON), helped lobby county government agencies. Their requests were the creation of a local Asian American COVID-19 task force, resources in more languages, and vaccine equity for Asian American seniors.

“I think it’s really difficult and challenging to understand the equity of it, to include Asian Americans in that, just because our data for COVID-19 is lacking,” Lee said. If there aren’t enough testing sites in low-income Asian American communities, for example, you’re not going to see the true infection rates reflected in the numbers, she said.

Many of California’s Hmong immigrants arrived as refugees from war and genocide and have struggled, remaining one of the poorest ethnic groups in the state.

What the data show, and don’t show

In 2015, Assemblyman Rob Bonta, who was recently appointed California attorney general, proposed a bill that asked state colleges, universities and a health agency to collect more detailed data on at least a dozen specific Asian nationalities, rather than lumping them into a single category. It passed unanimously in the state Senate and drew just one dissenting vote in the Assembly.

But Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed it. “Dividing people into ethnic or other sub categories may yield more information, but not necessarily greater wisdom about what actions should follow,” he wrote. “To focus just on ethnic identity may not be enough.”

Trinh and others argue that including all Asian Americans in one demographic category masks the diversity within such a varied group.

“I think people forget that Asia represents half the world’s population — literally, more than half,” said Trinh.

It’s about 60%, in fact, and can include people with heritage from, for example, Bangladesh, Japan and Laos, depending on the measure being used.

“So you have countries from all over the place with different experiences as to how [immigrants] get to the U.S. and different kinds of histories,” Trinh said.

Her family members are refugees from Vietnam, for example. She explains that Vietnamese Americans have higher rates of poverty, mental health issues and high-school dropout rates, which conflicts with the “model minority myth” that paints Asian American as successful and relatively problem-free.

“Asian Americans have the highest wealth gap,” she said, pointing to cities like Arcadia and Irvine that have high rates of vaccination and drive up the Asian American numbers.

This February, Bonta introduced AB 1358, a bill that would require further disaggregation of not only Asian and Pacific Islander subgroups, but Latino and Black ones as well.

Public opinion research may also paint a misleading picture of Asian Americans. A Harvard poll showed only 37% of Asian Americans reported financial difficulty during the pandemic, compared with 72% of Latino households, for example. The poll was conducted in English and Spanish. A Pew Research Center survey showed Asian Americans as a group that had minimal vaccine hesitancy — and was conducted only in English.

“The people who speak English tend to be more professional, tend to be higher income, tend to be tech-proficient,” Trinh said. “If they had focused on doing it in Cantonese, for example, I think the numbers would have looked really different.”

Maria Rosario Araneta, a professor of epidemiology and assistant dean of diversity and community partnerships at UC San Diego School of Medicine, is part of an AANHPI (Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander) COVID-19 Policy Research Team of more than 20 researchers and physicians who have met once or twice a month during the pandemic to discuss the missing data. They’ve done things like using names in obituaries to try to disaggregate data.

As of April 14, the number of deaths in California among the Latino community are the highest at 27,452, compared with white people at 18,317, Asian Americans at 7,092, Black people at 3,702 and other races at lower numbers, according to the California Department of Public Health.

But what also seems clear from the data, Araneta said, is that more Asian Americans who tested positive for COVID-19 ended up dying, compared with other races.

According to the California Department of Public Health, the case fatality rate in the state is 1.6%; whereas among Asian Americans, it’s 3.5%. In Los Angeles, even though Asian Americans had a relatively low COVID-19 positivity rate, they had the highest fatality rate among people who tested positive, at 5.58% — compared with Black people at 4%, white people at 4.12%, Latinos at 2% and American Indians/Alaska Natives at 2.38%.

Araneta said that if governments need to reach hard-hit Latino communities, many people can be reached in English and Spanish. “If they are Asian, that could be up to 42 languages,” she said. “That’s what makes it complex.”

At a vaccine clinic, a translator works with a woman who speaks Vietnamese

There have been signs that Asian Americans may be dying at higher rates for almost a year. In May, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that the Asian American community accounted for half the COVID fatalities in the city. Asian Americans make up about 36% of the city’s population, according to 2019 U.S. census data. In October, the California Nurses Assn. found alarming data on the pandemic death rates of Filipino nurses from the nursing labor unions. In the U.S., about 4% of all nurses are Filipino, but 31.5% of deaths among nurses were Filipino. In California, about 20% of nurses are Filipino, but Filipino nurses accounted for almost 70% of all COVID-19 deaths among nurses.

The first preliminary study to offer disaggregated data on Asian American COVID-19 patients came out in November. After testing over 85,000 patients in New York City’s public hospital system, researchers found that South Asians had the highest rate of positivity and hospitalization among Asians, second to Latinos for positivity and Black people for hospitalization. Chinese patients had the highest mortality rate of all groups.

The California Department of Public Health collects data that, for the most part, is aggregated by race — for example, Asian — but not by ethnicity. Of the limited data that does identify Asians by subgroup, case-fatality rates in November were especially startling for East Asians: Korean Americans (61.8%), Japanese Americans (57.2%), Chinese Americans (49.5%) and Taiwanese Americans (45.5%).

But the data are so limited that they’re impossible to draw firm conclusions from.

Araneta doesn’t know whether these numbers are a result of these communities getting tested at lower rates, whether there are medical conditions more prevalent in these communities that might affect the fatality rates, or if there is another reason.

Araneta also found evidence that while the vaccination rates in San Diego for Asian Americans are, as a whole, higher, the rates for Asian American seniors are lower than the average. The percentage of Asian Americans over 65 vaccinated is at 54.1%, compared to the average (76%) and closer to the percentages of Black people (47.4%) and Native Americans/Alaska Natives (56.2%).

She believes those numbers may show that seniors are “sheltering in fear,” because of escalating anti-Asian violence. In February, an 83-year-old Filipina woman, who has been identified only as Lola (grandmother), was attacked on a San Diego trolley. It was not deemed a hate crime. A month later when she talked to local TV news in Tagalog, she said the bruising on her head was gone but she still feels pain when she puts pressure on it.

One thing is clear to Araneta: “No data implies no problem — or that we can ignore it. It informs where resources go.”

The latest openings come on the heels of the news that anyone age 16 and older is eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine at city-run sites beginning Tuesday.

Vaccines in Chinatown

On Feb. 25, the nonprofit CORE (Community Organized Relief Effort), the Los Angeles Fire Department and L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office hosted the first mobile vaccine clinic in Chinatown.

CORE and LAFD mobile teams serve different districts each week through these pop-up clinics, said Daniela Burza, the Los Angeles mobile site manager for CORE.

That week, they had eight mobile teams operating in eight districts. They received locations from the mayor’s office, and the sites were kept private so as many doses as possible went to the high-risk, low-income communities they were allocated for.

For the Chinatown pop-up, Burza said they partnered with volunteers such as Trinh from SEACA.

“They provided the site with translators to assist us with the check-in process and guide patients during the entirety of their visit, ensuring a successful operation,” she said. “We could not have done it without them.”

Trinh rallied the rest of the local community organizations.

“If you want a big group to come and get vaccinated, you need to have organizations that have their trust to bring these community members out,” Cheng said.

He and his staff spent a lot of time convincing patients that Moderna was not better than Pfizer for Asian Americans — a rumor that circulated within the community — and that it would be safe for them get the Pfizer vaccine in an outdoor parking lot, even though many of them preferred to get it through the Chinatown Service Center.

Trinh said that the city wanted to train them on the city’s reservation system, but she told them that wouldn’t work. They knew it’d be more efficient to call people.

The plan was to vaccinate 800 people, 200 a day, but they were able to exceed that number with leftover doses from other clinics. Burza confirmed they vaccinated almost 1,000 people, no doses wasted.

“This shows that our strategy works, by basically thinking about going into these communities and being proactive to remove as many of those barriers,” said Trinh.

Araneta said that San Diego has also been successful at vaccinating their Pacific Islander population, which has had one of the highest rates of COVID infections of any racial or ethnic group in California. She believes the high vaccination rate is largely because San Diego is home to the largest Pacific Islander Festival in the nation. As a result, there’s an existing network and infrastructure to get the word out and bring the community out for vaccinations.

She also praised her medical and pharmacy students at UCSD who have led efforts to knock on doors and get vaccinations to Vietnamese, Guamanian, Samoan, Korean and Karen (from Myanmar) communities, as well as refugee communities including Somalis and Ethiopians.

“But is it our responsibility?” she said, “or is that the responsibility of the county health department?”

Thu Quach — a chief deputy of administration at Asian Health Services and a founding member of PIVOT, a progressive Vietnamese American network — recently led an effort to start a website, Asian American Voices, to collect stories of Asian Americans who have had difficulty getting the vaccine due to language barriers.

She said these stories will be “instrumental when we go to the federal government to say, ‘This shouldn’t be happening, and we have evidence that it’s happening. And it’s happening everywhere.’”

She wants people to feel free to share their stories, even if it’s not something they think is “serious.” For example, maybe they had to take a half day off work to get their limited-English-speaking parents a vaccine appointment.

“But our thing is, everything is serious,” she said. “That shouldn’t be happening.”

“So many community organizers are stepping up to fill that void without any resources, and this is not right,” she added. “We can keep doing it, we can applaud these wonderful organizations for doing it, but on the other hand, we need to call it out — that it’s not right that we have to step in.”

Times staff writer Jennifer Lu contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.