Financial ruin. Possible destruction. What will be the Cinerama’s Hollywood ending?

Their early audiences called them “flickers,” and it was a better name than they realized. Because — as the lights going out on the Hollywood Cinerama remind us — almost everything about the movies can end up short-lived and elusive.

Stardom is like that. Actors whose fabulous faces were celebrated on several continents and whose fabulous salaries were celebrated by their bankers could and did die unknown and broke.

So were movies themselves — throwaway amusements, no more durable than a Ferris wheel ride. Whoever foresaw the immortality of cable TV syndication, cult followings and DVDs? Physical film could go up in a fiery whoosh. Unstable and volatile, nitrate film stock can actually self-conflagrate. The thousands of silent films lost in spontaneous studio fires were the cinematic equivalent of losing a wing of the Louvre. L.A.’s first film-stock fire, in January 1905, was in a “motion picture storeroom” at 1st and Spring streets downtown. It belonged to a bumptious, far-sighted showman named Thomas Lincoln Tally, who in 1902 had already opened L.A.’s first dedicated movie theater, on Main Street, a few blocks away. Keep his name handy; you’ll be wanting it presently.

After that, the fire chief wanted all film stock to be stored in iceboxes. The daughter of the comedian Stan Laurel, the ectomorph half of Laurel and Hardy, remembered a summer in the mid-1930s when Beverly Hills firemen went house to house, collecting canisters of nitrate films as a precaution against fires, and her mother dutifully handed over some of her father’s movies.

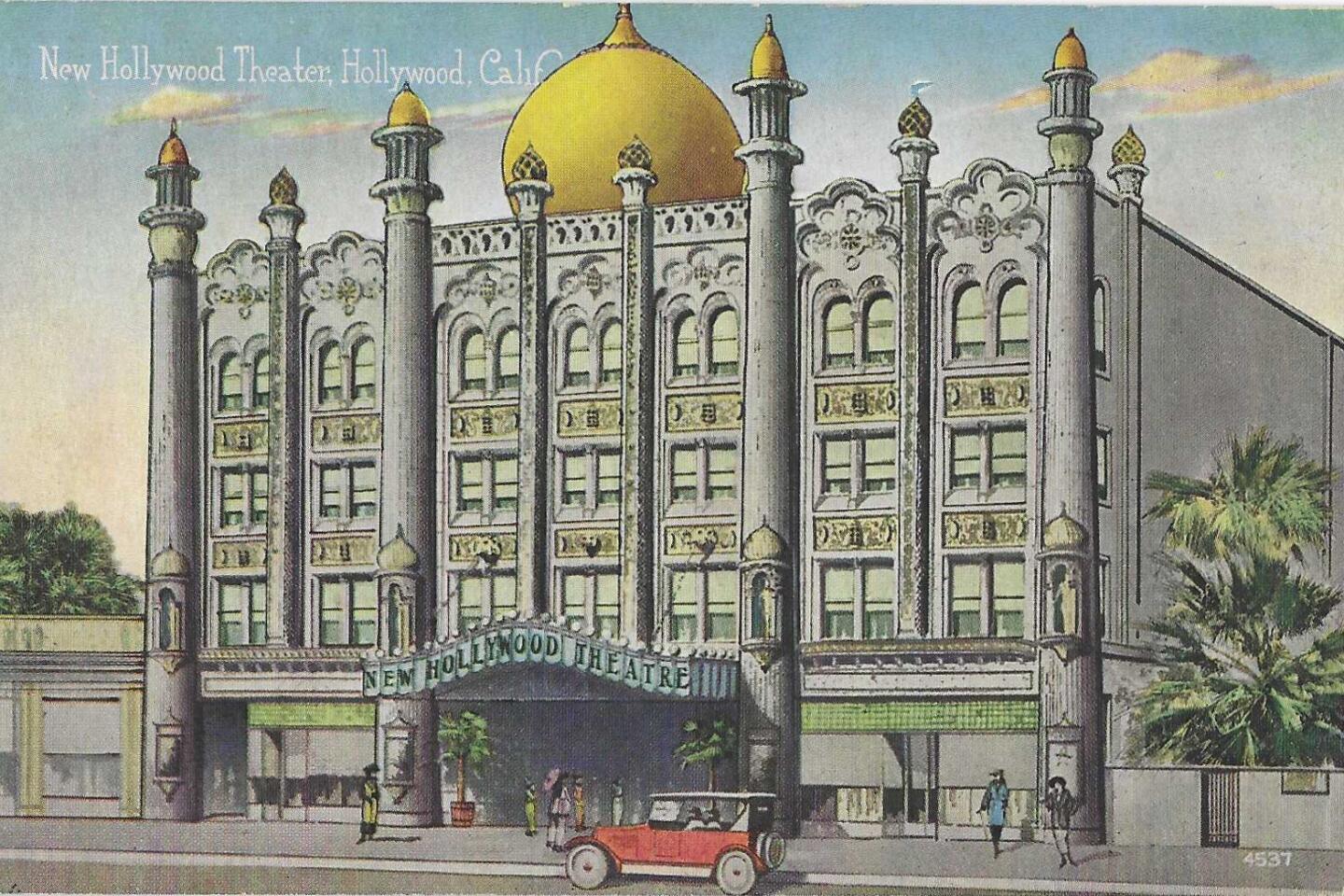

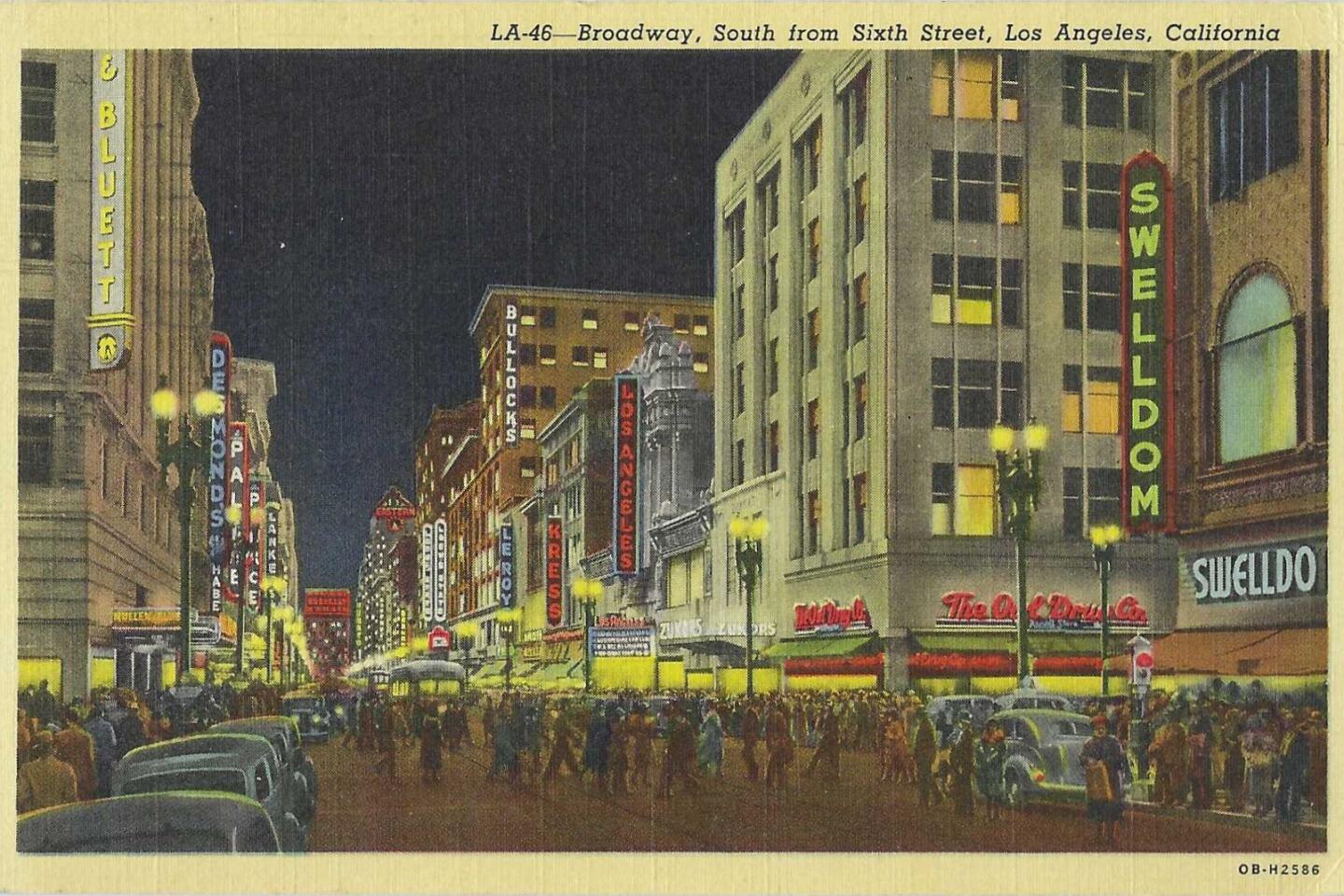

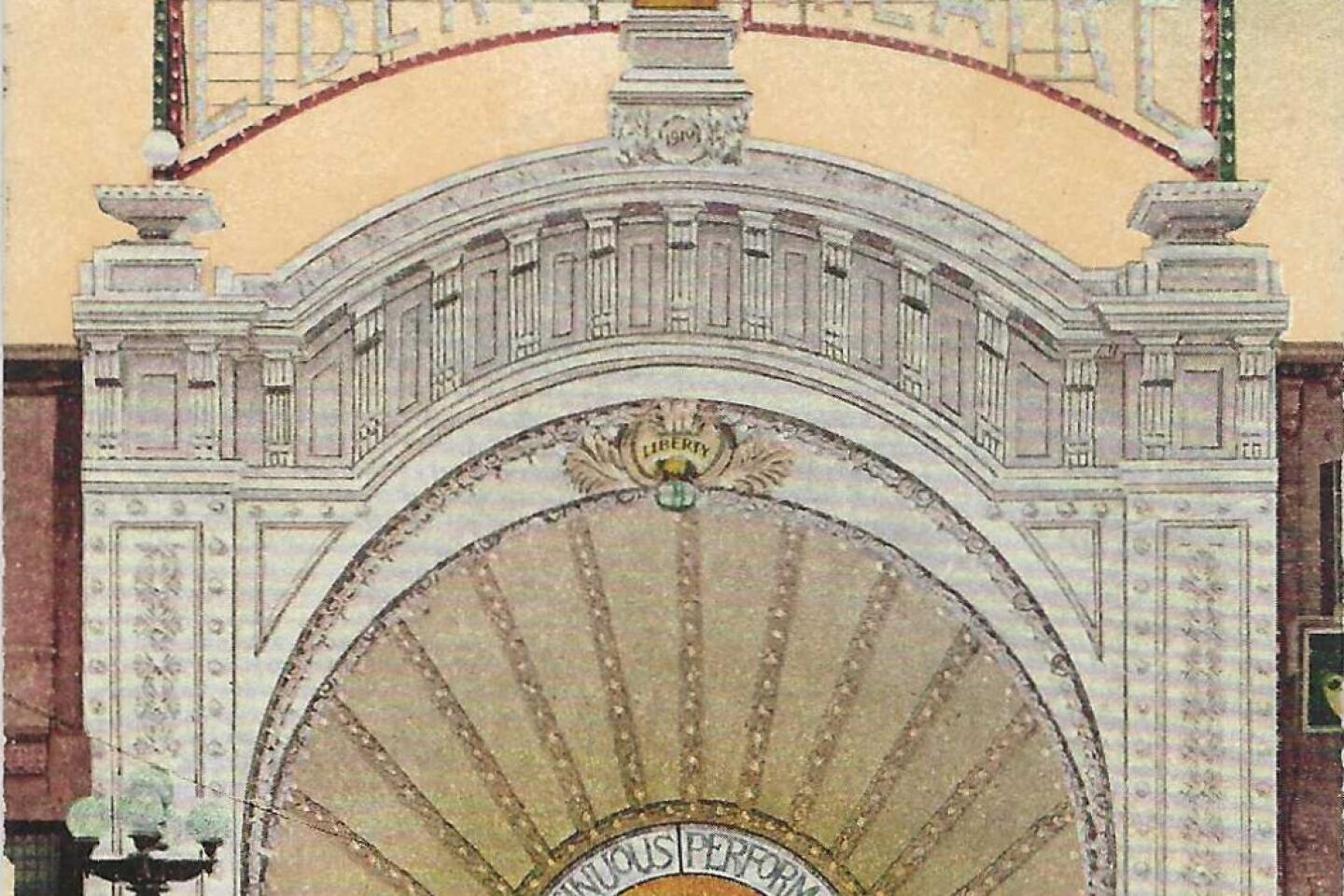

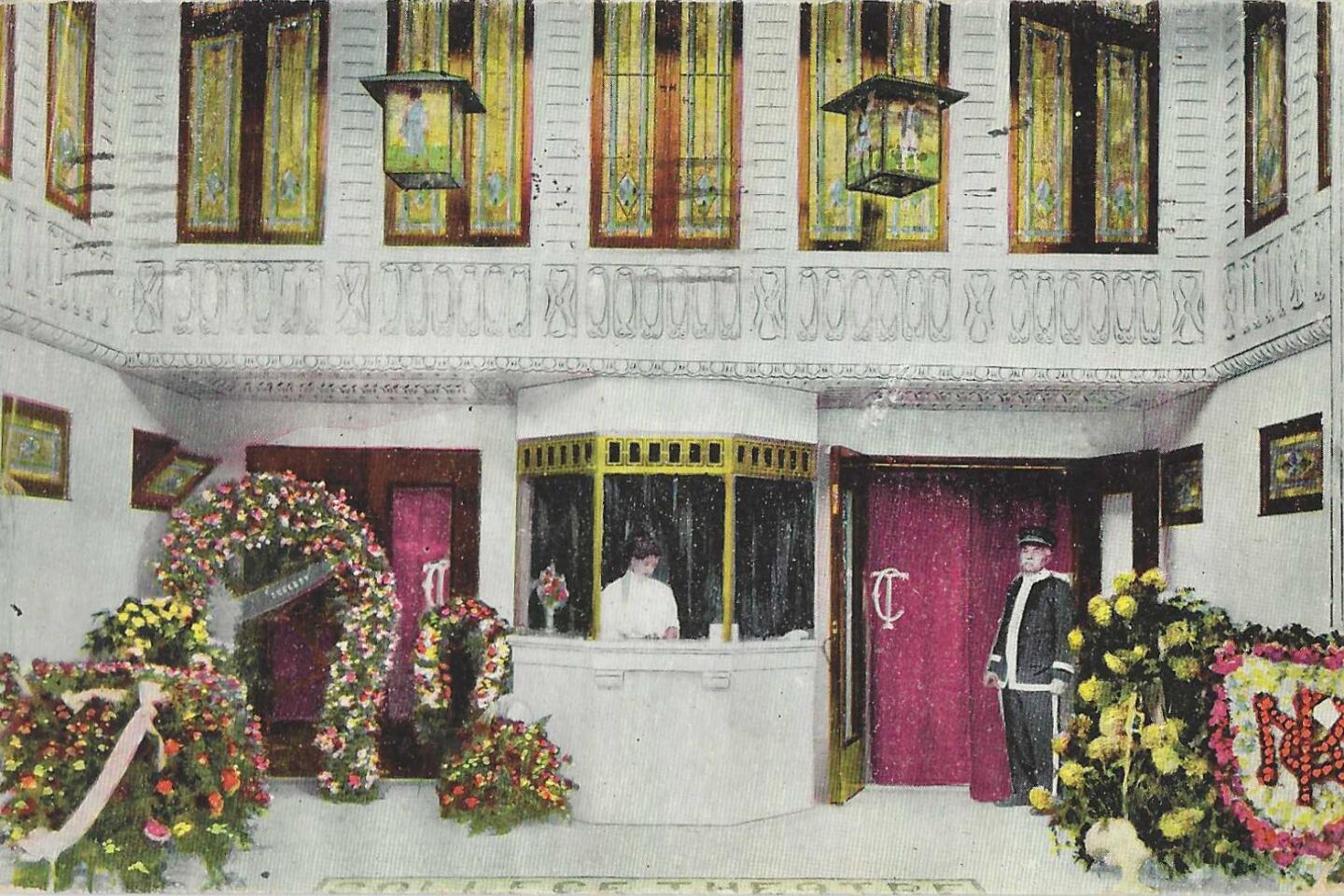

And then, those movie houses. They grew from hole-in-the-wall dime joints into splendiferous Versailleses with popcorn, places that looked as though they would outlast the Pyramids.

Does the Cinerama join them on the road to an oblivion where a movie screen is no more special than some pixels you carry in your hip pocket?

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

For L.A.’s theaters, the long, long cycle of build, remake, take down frequently feels urgently alarming. If the Cinerama isn’t safe, what is? The marquees of defunct and destroyed movie theaters could populate a Hollywood not-forever cemetery. Our above-the-title billing as “movie capital” was never protection enough. I half-believe that one-screen theaters in one-horse towns lasted longer because that was the only show around. The State Theatre, in Washington, Iowa, is still showing movies almost 125 years after it opened, serving popcorn from a machine that began its work in 1948.

As for the Cinerama, it has already survived cliffhangers worthy of Saturday matinee serials.

The Cinerama company, with its widescreen projection process, predated the Buckminster Fuller-dome theater. The dome was quite sturdy, but the company finances, not so much. A year after the Cinerama’s first showing, 1963’s “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World,” the company noted blockbuster losses, and the next year, it moved its headquarters from New York to L.A. to save on overhead. The owner, William R. Forman, twice dipped into his own pockets to stay out of bankruptcy. Soon thereafter, the company bought back its public stock.

Cinerama’s fortunes oscillated like a boardwalk roller-coaster, but it kept its panache and its cachet. The Cinerama is where, in 1990, Cecil B. DeMille’s “Ten Commandments” parted the Red Sea again, this time in 70mm Super VistaVision and six-track stereo.

Cinerama’s geodesic dome may soon be or may never be sacred rubble, yet its on-the-bubble future is a good moment to chart the sagas of L.A.’s movie theaters.

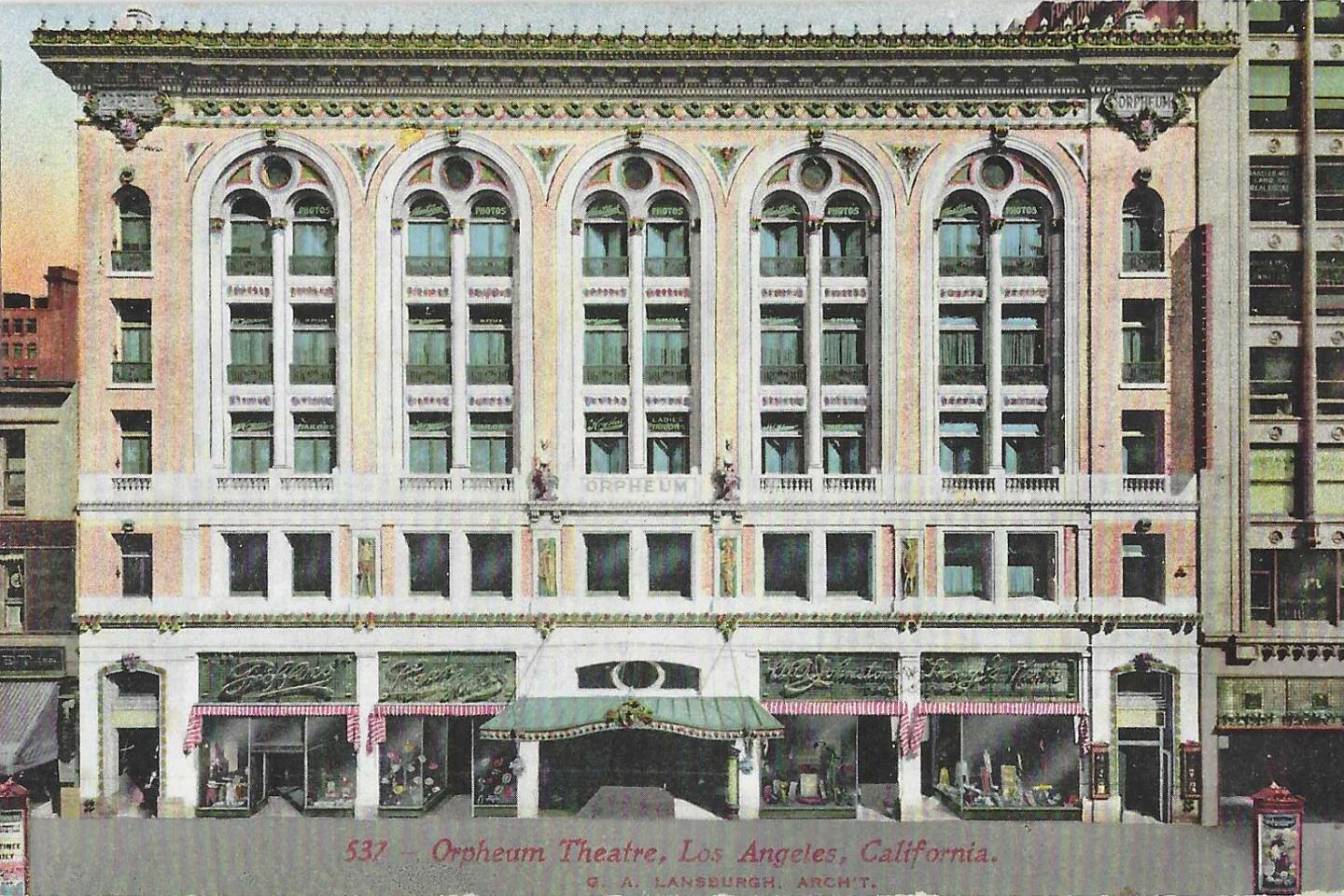

That many mouthwateringly beautiful movie houses in downtown L.A. still survive is thanks to many factors — among them benign neglect, repurposing (churches, swap meets, porn houses), and especially the vigilance and vision of preservationists like the Los Angeles Conservancy and of far-sighted property owners.

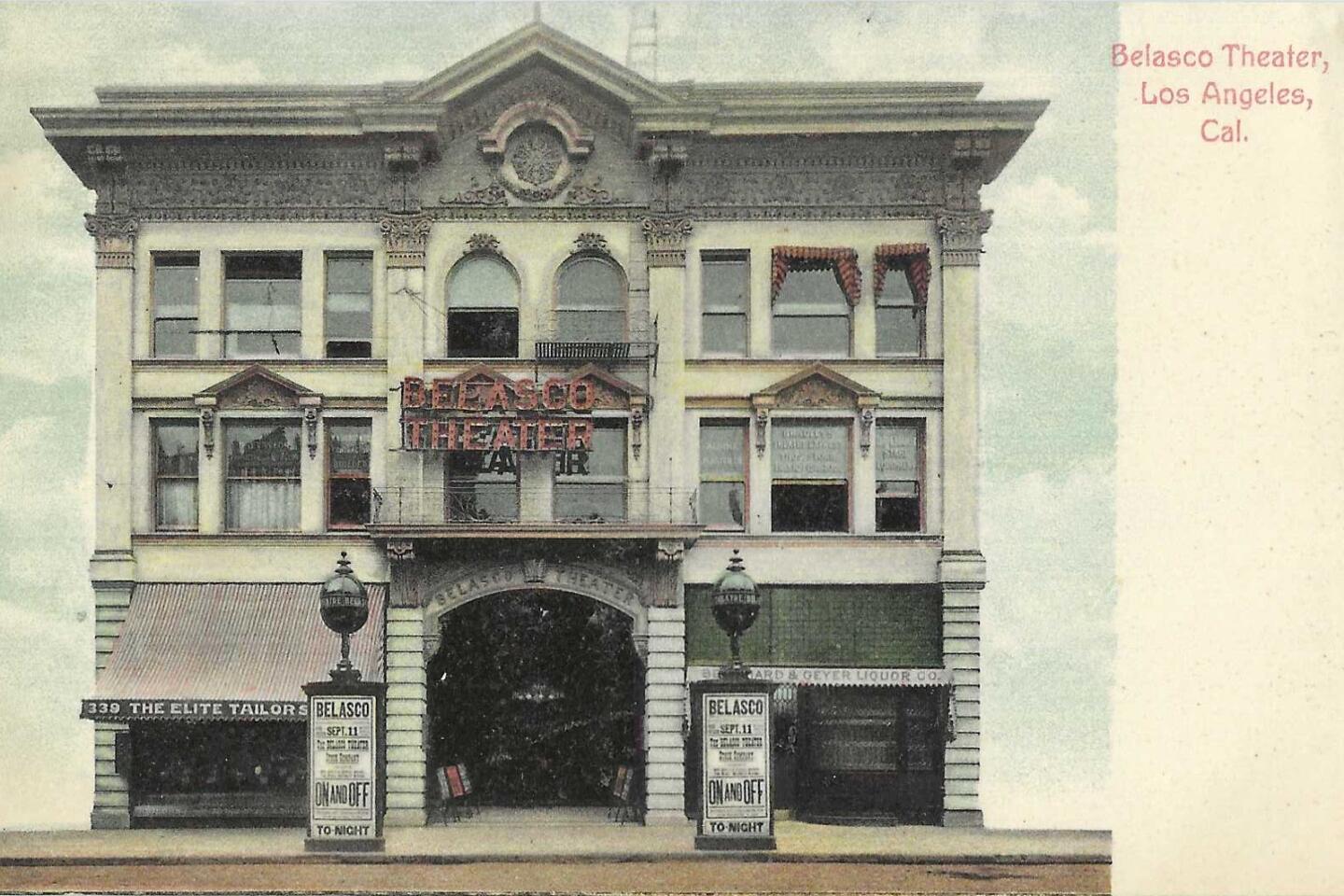

A long decade before DeMille had so much as sniffed a Hollywood orange blossom, that fellow Tally was already showing moving pictures in theaters downtown, the first of them his Electric Theatre, in 1902.

Three years before his pictures moved, Tally’s “Mutoscope” parlors, with their flipbook illusion of the motion of not-quite-unclad women, had attracted official pecksniffery over their depraved undoing of male morals. “If they try to close up my machines,” Talley warned in return, “I’ll close up studio and art gallery in Los Angeles,” where people could find the same thing, “and right out on the counters too.”

Anyway, he concluded, they should blame his younger brother, Edward, who ran Edison photo parlors on 1st Street; Edward showed those pictures first, so Thomas was just keeping up with the competition.

To make sure audiences wouldn’t think the bill at Tally’s Electric Theatre was another of his louche offerings, his L.A. Times ad for the April 1902 opening pledged “a refined entertainment for ladies and children” — one hour’s worth for 10 cents, “interesting scenes” like the re-created capture of the criminal Biddle brothers, capped with a gun battle in the snow. (Proving that Hollywood never wastes a good idea, Diane Keaton starred 82 years later in “Mrs. Soffel,” a film about the prison warden’s wife who helped the Biddles escape.)

Tally had no qualms about declaring that his Electric was the nation’s first movie theater. But “first” is always an iffy honor, and Pittsburgh says it owned the country’s first “stand-alone” theater, in 1905, three years after Tally’s “refined” entertainment. Maybe the distinction is “stand-alone,” but I’ll give the palm to Tally.

Such was Tally’s faith in the future of movies that in 1909, he bought a 50-year lease — 50 years! — on a property on Broadway to build a new theater. For this, he paid what The Times reported as the mind-bending sum of $600,000. He didn’t get even half his money’s worth; the theater was knocked down about 20 years later, and Tally died in 1945.

The great movie-house boom found a welcome in L.A.’s diverse communities. The old Kim Sing Theatre on the northwest edge of Chinatown, originally the 1926 Alpine Theatre, was re-done by Harrison Ford’s son and serves as an event site that once hosted a Katy Perry pop-up shop.

I used to walk past the raddled marquee of the shuttered Linda Lea Japanese Films theater on Main Street near skid row. Now it’s a one-screen independent theater. A nostalgic fan posted an online memory of visiting the Linda Lea when “the men’s restroom had ‘scratching plates’ mounted on the wall next to the urinals so the men could strike their matches and light up a smoke while answering nature’s call.”

What was for many years the country’s biggest (and internationally famous) Spanish-language theater, downtown’s fantastically elaborate Million Dollar, began its life in 1918 as showman Sid Grauman’s dress rehearsal for building his future and even more grandiose Egyptian and Chinese theaters in Hollywood.

By then, L.A. was preening itself over movies’ magnificence and munificence. But in 1906, civic moralizers thundered in The Times, which regularly printed racist slurs in this and other contexts, about the “handbooks of crime” being shown in moving picture houses to integrated audiences.

Obviously even then Black Californians were being banished to theater balconies or excluded altogether. A few movie houses — such as the Lincoln Theatre on Central Avenue in South L.A. — were built for Black patrons and performers and as homes to Black-made films. In its latest 60 years, the Lincoln has been converted to religious purposes, and at least until the pandemic, Spanish-speaking congregants were treated to weekly summer movie screenings.

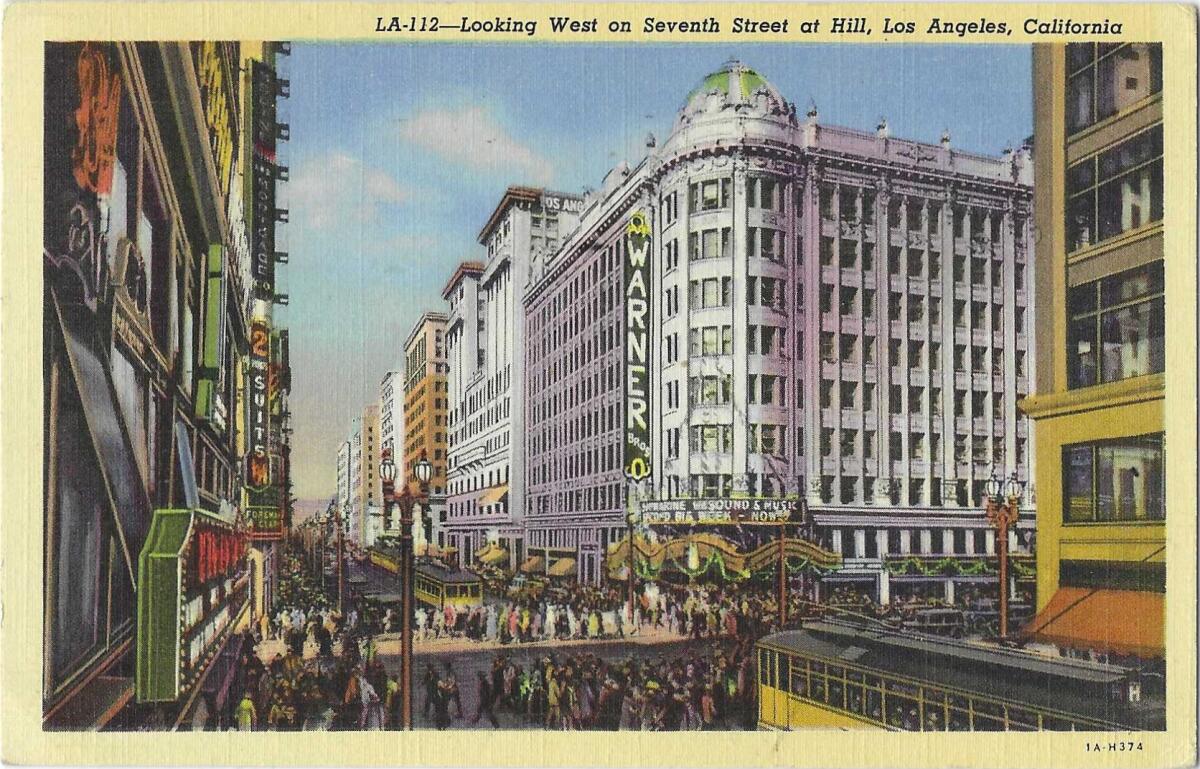

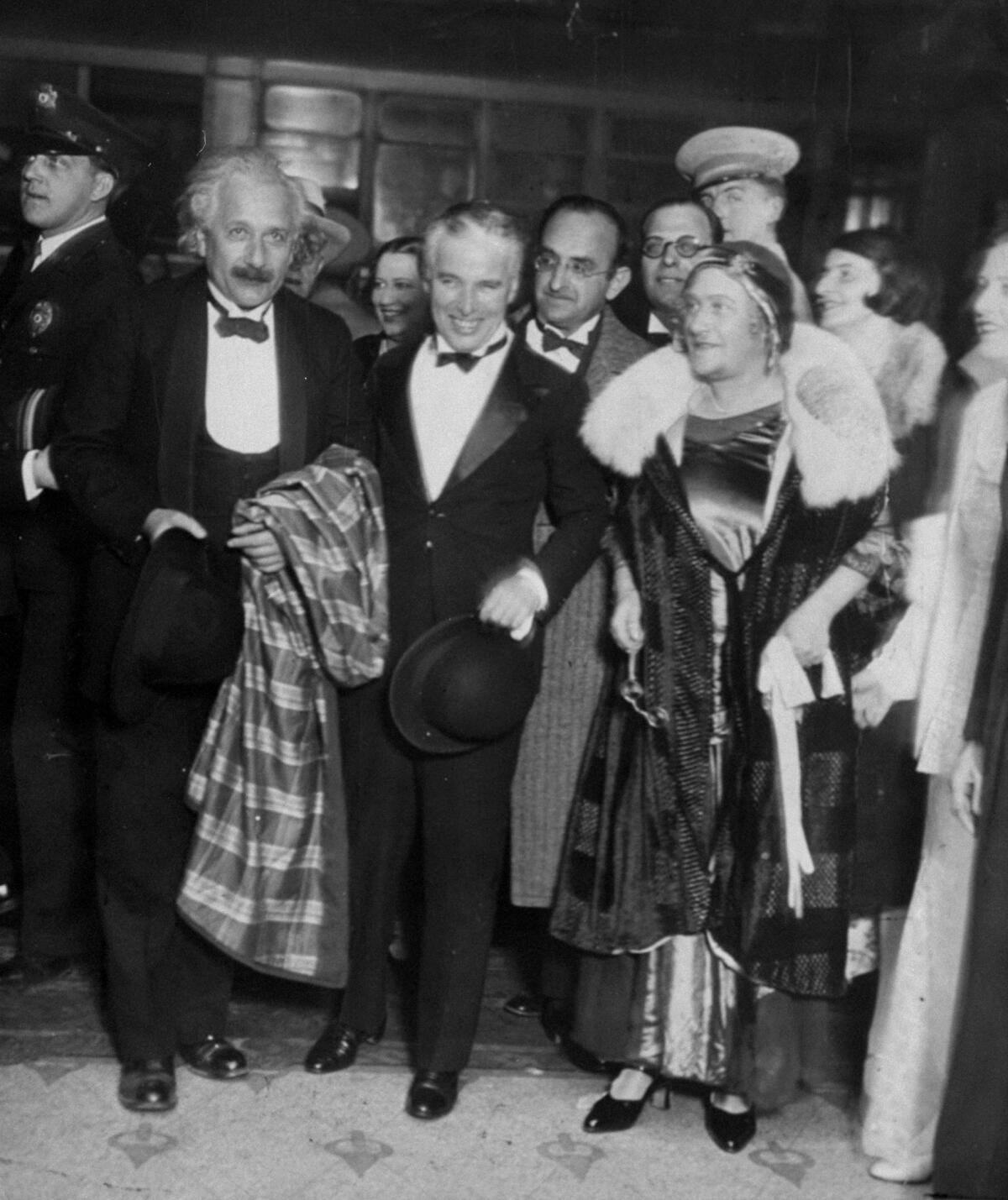

The fortunate theaters reinvented themselves, from vaudeville to film to … pretty much whatever was on offer. The downtown Pantages begat the Warner Brothers which begat the jewelry mart. Others survived the evolution of tastes and technologies: the Orpheum, with its effulgence of neon out front, and the Los Angeles, opened in 1931 with Charlie Chaplin’s “City Lights” and among its premiere guests, Albert Einstein.

What got the short straw? Places like the Burbank Theater — now a parking lot. The Hippodrome? Parking lot. Wreck and repeat.

A few ended up showing X-rated movies, some furtively, some boldly, like the Pussycat Theatre on Western Avenue, originally the 1926 Sunset Theatre, and the flagship of the Pussycat chain.

The owner of the chain, Vincent Miranda, had been arrested so often that when I interviewed him in his office in the 1980s, his desk nameplate read “Defendant Vincent Miranda.” He made sure to point out to me that there was never anything dirty posted in front of the theater lest some schoolkids see it. But he couldn’t stop talking down the huge discount mart just down the street: “This neighborhood has gone downhill,” this porn-theater mogul fumed to me, “ever since that Zody’s went in.”

Out in far suburbia, suburban cineplexes left most of the single-screen showplaces in the rear-view mirror. A restored Westlake Theatre is a mere promise, but the massive rooftop neon sign still lords it over MacArthur Park. The handsome Fox in Westwood (now known as Regency’s Village Theatre) and the lovely Alex in Glendale carry on with elan. In San Pedro, locals worked diligently and actually raised the money to revive and maintain the 90-year-old city-owned Warner Grand to the splendor of yore.

(If I didn’t cite your favorite here — I didn’t forget it. It’s just that other reporters would like me to leave some space for their stories too.)

The ArcLight Hollywood with its Cinerama Dome means a great deal to Hollywood the neighborhood. Here’s hoping for a rescue that saves it but doesn’t try to reinvent something that works.

As for the Cinerama, how can it be saved from landing at the top of the roll call of movie theaters that exist, like movies themselves, in image only?

The Hollywood sign was rescued several times over by big-name big donors.

But I had in mind a fundraiser from 1885, when the immigrant New York newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer ran a crowdfunding crusade to help pay to finish the pedestal whence the Statue of Liberty could lift her lamp in New York harbor.

Immigrant workmen gave up a pay envelope, schoolchildren put in pennies — upward of 150,000 people in all, each name and each donation noted by Pulitzer’s New York World, and almost each one under a dollar.

Maybe such a “Save the Cinerama” campaign could work, if only because it gives movie fans all over this mad, mad, mad, mad world a way to see their names flicker on a Cinerama website and to say, in truth, “I made it in Hollywood!”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.