Olympic athlete Sakura Kokumai targeted in anti-Asian rant in Orange County

She saw the man before she heard him.

Sakura Kokumai, a karate champion slated to represent the United States in the 2021 Olympic Games, was wearing headphones as she warmed up on a recent weeknight for a run at Grijalva Park in Orange.

“This guy was yelling, and I looked over my shoulder to see if there was anybody in the direction he was looking at, but I didn’t see anybody” said Kokumai, 28. “That’s when I knew this guy was yelling at me.”

The man’s verbal attack grew increasingly aggressive, and she starting taking video of him with her cellphone.

“You’re a loser. Go home, you stupid b—,” he said. “I’ll f— you up.”

At one point, he can be heard yelling the word “Chinese.”

Kokumai, who was born in Hawaii, is Japanese American. She is also the latest victim in a string of anti-Asian attacks that have taken place around the country, including Orange County.

“I was trying to process what was happening, but at the same time, I realized he was far bigger than me,” she said. “As much as I know that I practice karate and I am an athlete and I’m quick on my feet — you still don’t know what can happen.”

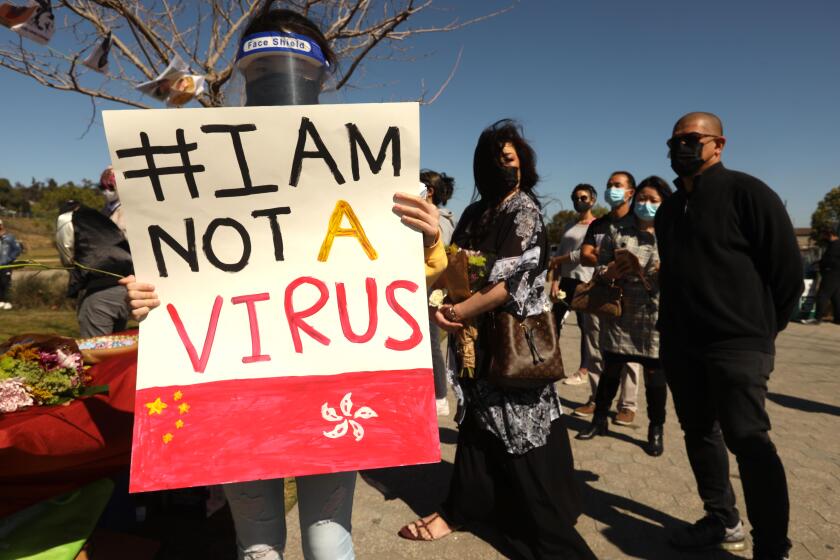

In recent months Orange County has seen a substantial increase in hate incidents and attacks against the Asian American Pacific Islander community, according to Alison Edwards, CEO of Orange County Human Relations, a nonprofit that works closely with the county to track and respond to hate crimes and racism. Hate incidents include lawful activities motivated by hate, like racial slurs, she said.

“We’ve been collecting hate crime data in the county for about 30 years,” Edwards said. “This rise is very significant, very alarming.”

In 2020, the county saw a tenfold increase in hate incident reports, Edwards said. The area is currently in the midst of another wave, including the recent assault of a 69-year-old Asian man in Irvine and a separate incident involving rocks being thrown at an Asian mother’s car in Fullerton.

One Ladera Ranch family was repeatedly harassed with rocks, verbal attacks and pounding at their door over the course of several months.

Reporting center Stop AAPI Hate counted 3,795 racially motivated attacks against Asian Americans nationwide from March to February.

The incident at Grijalva Park happened around 5 p.m. April 1, when the park was busy, Kokumai said, noting that several people walked by without offering to help. It wasn’t until the end of the exchange when a woman with a dog asked if she was all right.

“It felt like the longest time where the interaction was happening, but nobody did much,” Kokumai said.

Kokumai has not decided whether she will file a police report, but said she shared the incident with her 25,000 Instagram followers to get the word out.

“The scariest thing about this entire process was that this really could have happened to anybody, and the thought of it happening to the people I know really scared me,” she said. “We all just need to look out for each other.”

About 68% of the anti-Asian attacks documented during the pandemic were verbal harassment, 21% were shunning and 11% were physical assaults.

While it is difficult to pinpoint a single cause for the increase in attacks, experts say anti-Chinese rhetoric rising from the COVID-19 pandemic played a very large part. In 2020, then-President Trump called the coronavirus “the Chinese virus.”

In March, the Orange County Board of Supervisors, prompted by the surge of attacks, passed two resolutions denouncing hate and declaring a commitment to action.

“Since the start of the pandemic, inflammatory, racist language used by our elected officials and amplified on social media has led to an increase in crimes directed against Asian, Black, Latino, Indigenous, Middle Eastern and other people,” Supervisor Andrew Do said in a statement about the resolutions. “When racists are emboldened to act out their racist thoughts egregiously and blatantly, any soft pedaling will only encourage more victimization.”

Edwards, of OC Human Relations, said people who witness an attack don’t have to place themselves between the victim and the perpetrator in order to help. There are other tactics, including the “Five Ds” of distract, delegate, document, delay and direct promoted by anti-harassment group Hollaback.

“It could be as simple as standing with them physically so that they know they have someone with them,” Edwards said.

If you see someone harassing or being violent toward another person, what are your options to act and intervene safely? Plus more tips on how to be a good ally.

The county is working on other efforts, like increasing language capacity in their data collection and reporting system and giving workshops on how to be an upstander, or a person who intervenes on behalf of a person under attacked, she said. They also offer support services and other resources for victims.

And although not everyone may want to report such racist incidents to law enforcement, Edwards encouraged the community to let OC Human Relations or another trusted group know when these attacks occur.

“We really want people to report,” she said. “We’re trying really hard to get people to understand that there is support. There are organizations that stand with them.”

Violence and hate incidents directed at Asian Americans have surged across California since the pandemic, with some blaming Asians because of the coronavirus’ origins in Wuhan, China.

For Kokumai, the attack was a reminder that “we live in a world where we are being targeted for the way we look,” she said. In sharing her story, she hoped to raise awareness for her community and remind people that the issue is much bigger than one person.

“I’m proud to represent this country, and I’m proud to represent my sport, which is a Japanese martial art,” Kokumai said, adding: “We all belong here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.