From the KKK to skinheads, a century of fighting hate in Orange County

Orange County has evolved dramatically in the last few decades in ways that challenge its old stereotype as a white conservative bastion.

The county supported Democratic candidates in the last two presidential elections. People of color are the majority now, with big increases in the Latino and Asian populations. A “blue wave” in 2018 shifted key congressional seats from Republican to Democrat, though the GOP took back two of them in 2020.

Orange County is still more Republican and conservative than California as a whole — supporting local and national candidates who oppose COVID-19 health orders, for instance — but it is far from the right-wing monolith of the past.

Moreover, many have pushed back against the extreme views of fringe groups, often finding success through dialogue and both political and law enforcement pressure.

Four members of Orange County’s resurgent far right spoke at a pro-Trump rally in Washington the day before the Capitol riots. Their violent rhetoric targets foes both real and imagined.

“There’s two types of Republicans — there’s governing Republicans who understand you’re in government to get stuff done, and then there’s people who want to blow the whole damn thing up,” said Keith Curry, a Republican and former mayor of Newport Beach. “It is an absolutely losing hand to be associated with these radical extremists going forward. If you subscribe to that stupid stuff, it’s going to follow you like stink for the rest of your life.”

Public schools run joint programs with the Anti-Defamation League to reach both students and faculty, said ADL regional director Peter Levi, who is a rabbi. He said antibias training is core to that work, addressing attitudes before they result in ugly confrontations.

Levi said there also is a concerted effort within the interfaith community to combat racism and prejudice — one that includes Muslims, Christians and other religions. “After 9/11, there was a mainstream effort to find common ground,” he said.

Still, the far right remains a force. And it is building on a long history of extremism.

Here is a rundown:

The KKK

In the 1920s resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the white nationalist movement flourished.

Klansmen were once the dominant political force in Anaheim, holding four of five City Council seats before a recall effort led to their ouster in 1924.

At the height of the group’s power in Orange County, nearly 300 klansmen lived in Anaheim, patrolling city streets in robes and masks. A large KKK rally once attracted 20,000 people to the city. KKK patrols stopped and interrogated citizens, and once burned a large cross in front of St. Boniface Roman Catholic Church.

Anti-Klan residents had formed a group called USA Club — for “Unison, Service, Americanism” — and backed a slate of successful candidates in the statewide primaries of 1924. It took several years, but those forces finally pushed the KKK out of power in the city.

Anaheim is now majority Latino and no longer a hotbed of extremist politics. But in 2016, there was an alarming echo of that ugly past. A Ku Klux Klan rally in Anaheim turned violent that year, leaving leaving three people with stab wounds and several arrests.

It wasn’t just the fliers that alarmed locals — it’s what they were promoting: a “White Lives Matter” rally scheduled in Huntington Beach.

Minority restrictions

Social historian James Loewen described the entire county as a “sundown town” where Black people and other minorities were expected to leave before dark well into the mid-century, noting that most Orange County communities “were established as white only.” Such restrictive deeds that prevented homes from being resold to minorities were commonplace around the nation.

Chapman University sociologist Peter Simi said a Native American recalled to him the necessity as a child in Tustin of staying out of public places after nightfall. Despite major growth in Asian and Latino populations, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated in 2019 that barely over 2% of Orange County residents are Black.

Post-war far right

During the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, the arms buildup and race to space against Russia brought large numbers of mostly white workers to defense and aerospace companies based in Orange County. This new population was so supportive of the John Birch Society and its conspiracies of communist threats that Orange County is sometimes mistakenly credited as the birthplace of the organization.

Berry farmer Walter Knott converted his produce stand into a patriot-themed park, including a replica of Independence Hall. He sponsored a large School of Anti-Communism and library devoted to the communist threat. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in 1966 was advised to steer clear of Knott, who invited Hoover to Orange County to receive an award. Confidential staff memos described Knott as “a militant anticommunist who supported a number of rightest organizations in California.” Among Knott’s perceived enemies was the American Civil Liberties Union.

Conservative Christian churches promoted anti-Communist as well as blatantly anti-Semitic views, and hosted right-wing political speakers, according to Harvard historian Lisa McGirr in her book “Suburban Warriors.”

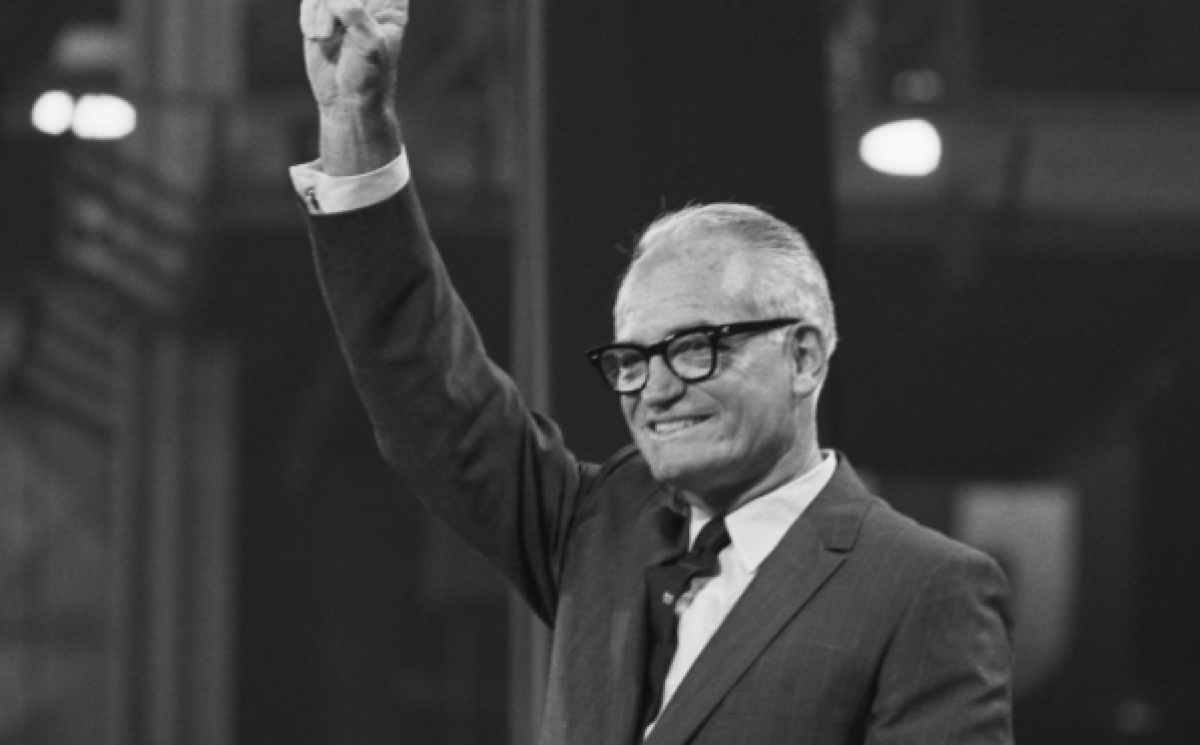

Orange County was a driving force in the anticommunist and often racist rhetoric that had sprung out of the 1964 presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater.

McGirr and other historians credit his support in Southern California — including a volunteer campaign dubbed “Operation Q” — for Goldwater’s success in qualifying for the California primary and then beating the establishment Republican contender Nelson Rockefeller. After winning the Republican Party nomination, Goldwater wound up losing the presidency in the most lopsided national election in U.S. history, but his militant “rightest” followers took control of the California Republican Assembly and the party agenda.

They promoted conservative views on not just politics but also morality and social change. They portrayed themselves as torch bearers for the Founding Fathers, not far afield from Trump supporters who call themselves “Patriots” and liken their efforts to keep Trump in office to the American Revolution.

A few years later, one of Goldwater’s admirers, Ronald Reagan, was elected California governor, and went on to the presidency in 1981.

Orange County also produced Richard Nixon, who at first sought to evict Birchers from the state GOP but eventually campaigned for Goldwater and later adopted his social conservative themes to win the presidency in 1968 — bringing the Western White House to San Clemente.

Skinheads

In the 1980s and 1990s, skinheads became a problem in Huntington Beach and beyond.

There was a series of attacks on Black, Latino and Asian residents that sparked alarm and outrage. In one notorious case, a Black man, Vernon Windell Flournoy, was killed outside a McDonald’s restaurant in Huntington Beach. The skinhead charged in the killing was also accused of trying to kill two Latino men.

Though the ADL classified California as having the nation’s largest concentration of skinheads, the beach town appeared to be the epicenter. The Times wrote in 1993: “Since the mid-1980s, Huntington Beach, famous for its surfing scene, has also been something of a magnet for skinheads. Its pier and downtown area have been gathering spots for young people whose shaved heads, swastika tattoos, steel-toed boots and racist philosophy mark them as ‘skins.’”

The FBI in 1993 publicly identified the skinheads as part of an alleged white supremacist conspiracy to attack African Americans in Los Angeles and ignite a race war.

The violence prompted city officials to take action, creating a Human Relations Task Force to promote and celebrate cultural diversity. The county also began “days of dialogue” marked by frank discussions on diversity and prejudice.

Rise Above Movement

Two decades later, the Rise Above Movement was founded in Orange County, attracting dozens of members to the white supremacist group. They trained for hand combat against counterprotesters who appear at right-wing rallies and demonstrations. Four members pleaded guilty to federal charges from the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va. Three other members await trial on federal anti-riot charges for their alleged violent roles in conservative rallies from Berkeley to Huntington Beach.

Ultra-conservative extremists have reemerged in local antilockdown and political demonstrations, from Yorba Linda to Huntington Beach.

Civic and political leaders have sought to address the wounds of extremism, from the Anti-Defamation League to the Orange County district attorney’s office. Schools embraced the ADL’s “No Place for Hate” program. In 2014, Cal State Fullerton opened a diversity resource center.

In 2018, batting down renewed criticisms that his community was again a haven for white supremacists, a frustrated Huntington Beach mayor asked his local paper: “How does a community shake a myth?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.