He was the king of water in the desert. His abusive reign revealed a troubling culture

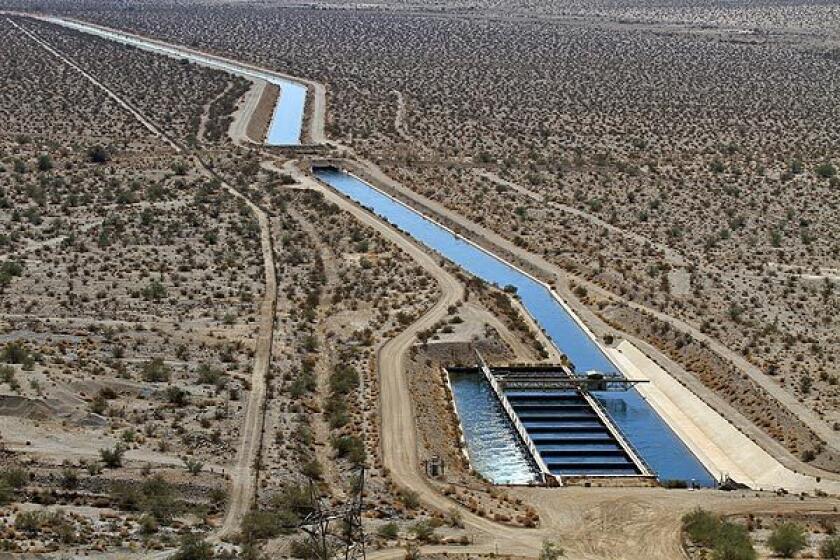

In the work camps of the sprawling Colorado River Aqueduct system, Donald Nash was known as king of the desert.

For more than half a decade, Nash was responsible for operating and maintaining the pumping plants, reservoirs and pipelines that deliver much of Southern California’s drinking water — while also exerting a tyrannical presence in the remote communities of aqueduct workers that have sprung up across desolate stretches of the California desert.

Coworkers said they complained about Nash’s abusive behavior and recklessness to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California as he became increasingly erratic over the years.

Nash was eventually fired in 2019. But his story, drawn from MWD records, court files and interviews with workers, reveals what some employees and members of the agency’s board of directors contend is a troubling lack of oversight in the largest distributor of drinking water in the nation.

It is also the story of what many workers describe as an untamed frontier of isolated worksites and company-owned housing, where everyone knows everyone and someone in a position such as Nash could wield power over subordinates.

Several workers recently accused MWD leadership of tolerating sexual harassment and abuse of women, particularly those in the trades apprenticeship program. Only nine of the 218 apprentices hired between 2003 and 2019 were women, according to agency records. Four of them have filed equal employment opportunity complaints, a spokeswoman said. Overall, 18 women worked in trades positions for the district between 2005 and 2019, records show. Six of those filed formal EEO complaints.

The district hired an outside firm to review how such complaints were handled.

‘They thought I was so low’: Women say they were harassed, bullied, ignored at powerful water agency

In interviews with current and former staffers and reviews of district records, court documents and audio recordings, The Times found a pattern of complaints alleging harassment and bullying of women at the Metropolitan Water District.

But the MWD’s 38-member board, representing several cities and local water agencies, is rarely given information about personnel matters unless they become the focus of lawsuits — it was never briefed about Nash. Board members sometimes venture into the field on inspection trips, but the visits aren’t the kind of fact-finding inquiries that might have exposed Nash’s behavior, some employees said.

In statements to The Times, a district spokeswoman said the agency “took seriously and responded to complaints against Nash.”

MWD General Manager Jeffrey Kightlinger said the district has committed to improving conditions and accountability at the desert camps. District officials say they are spending millions of dollars on new housing to improve the camp neighborhoods.

“We recognize the challenges that exist at these remote facilities and have undertaken a number of programs and initiatives to address them over the past two years,” Kightlinger said in a statement to The Times. “This includes adopting a philosophy of accountability and recognition that supports and empowers desert field managers. ... Our employees are important to us and we know that we can and will do better by them and their families.”

::

The MWD headquarters in downtown Los Angeles is a modern 12-story tower near Union Station. But the Colorado River Aqueduct is steeped in the history of Los Angeles and its explosive population growth in the early 20th century. It was conceived by William Mulholland, whose exploits in securing water rights in the Owens Valley via another aqueduct is the basis for the film “Chinatown.”

Construction on the Colorado River project began in 1933 employing “35,000 men who labored 24/7 in grueling Mojave Desert heat,” according to the MWD’s website. The 242-mile system includes reservoirs, pumping plants, siphons and tunnels 16-feet in diameter. Housing was built so workers were close by in case of emergencies and even schools were constructed.

In recent years, workers have complained about dilapidated conditions, including an open sewage leak. Because of problems with infrastructure, no cold water is available in the summer: Water supplies are stored in large tanks which bake in the heat and are delivered through shallow underground lines, employees said.

The desert facilities drew a hardscrabble lot who enjoyed “living on the moon,” said Charles Smith, a manager at the Iron Mountain water pumping plant in eastern San Bernardino County before he retired in 2019. During World War II, the area was used as a training ground to prepare armored divisions under Gen. George S. Patton for the harsh fighting conditions of North Africa.

The isolation and pressure of keeping the vast system running takes a toll on workers, and employees who can’t tolerate the environment often leave. The close living and working quarters only compounds tensions, many said. Recognizing the hardship, the MWD offers incentive pay to those who work at the remotest desert sites.

“You go to use the weight room, your boss is in there, or the pool, and there’s someone you don’t like you’re working with,” said Paul Williams, a retired aqueduct operator.

Many workers find their entertainment in off-road driving and guns. District camps include firing ranges, and shooting is a favored pastime.

“You didn’t know what you were going to get with him. Happy Don? Angry Don? Drunk Don?”

— Paul Williams, a retired aqueduct operator

It was the sort of environment in which disagreeing with someone’s politics gave him the feeling he could be killed, Smith said, especially since the nearest town was at least an hour’s drive.

Smith, who is Black, said he also experienced racist behavior. During his first week at the Iron Mountain plant, he said a white man blocked him from entering the kitchen, spat at his feet and called him the N-word.

He alleged that Nash, who is white, used the same racial epithet with him after a contentious meeting a few years ago, saying, “This is my desert. I do what I want.”

“It’s like The Hills Have Eyes out there,” Smith, 66, said in a reference to horror films about ghoulish desert marauders.

::

Nash spent most of his life in the desert. He was born and raised in Blythe, Calif., and served in the Navy before going on to work for the district in 1991 when he was 24. Even his detractors admired his vast knowledge of the aqueduct system. A tallish man with salt and pepper hair and a boyish grin, he had a magnetic confidence, and workers described wanting to hang around him to soak up his brilliance.

“He was a very handsome, rugged cowboy kind of guy,” said Bernice “Bernie” Stillions, a former MWD tour manager who retired in 2012.

Nash was a protector and mentor to some.

Theresa Cross, a tradeswoman who previously worked at the Iron Mountain camp, recounted an incident in which a former manager sexually harassed her and she shoved him away. She drove off into the desert in a panic.

Nash intervened, made sure she was safe and called in the complaint for her.

“I was hysterical, shaking, didn’t know what to do,” Cross said. “Don was my guardian angel.”

Nash thrived in a work hard, play hard culture at the desert camps. After a stint as a camp team manager, he was promoted in 2012 to oversee conveyance and distribution for the district’s desert region, consisting of the pumping plants and camps that run from the outskirts of Joshua Tree National Park to the Arizona border. His company house was at the Whitsett intake plant along Lake Havasu, a short drive from the district’s Gene pumping station, one of five that lift water over the mountains.

New Yorker writer David Owen interviewed Nash for a magazine piece and his book “Where The Water Goes: Life and Death Along The Colorado River.” In the book, he wrote that Nash’s role as the aqueduct manager was not quite as lonely as a lighthouse keeper, “but not by a huge margin.”

As Nash rose through the ranks, so did his pay: He earned $268,000 in salary and benefits in 2018, public records show, and owned a Cessna 182 single-engine airplane. He was among several desert workers who owned aircraft for pleasure.

Nash and employees called the expanse of desert around the aqueduct “Nashville.” He and his coterie drank beer and whiskey sometimes until work started the next morning, employees said.

But his personality seemed to take an alarming turn after he and his wife filed for divorce in late 2014.

He was deeply bitter about the separation, coworkers said.

“You didn’t know what you were going to get with him” after the divorce, Williams said. “Happy Don? Angry Don? Drunk Don?”

Employees complained repeatedly about Nash’s behavior at least from 2014, MWD records and interviews show.

Allegations of sexual misconduct at the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California reflect a history of mistreatment and disrespect of people.

In 2014, complaints alleged that Nash sat on a panel interviewing job candidates, one of whom he was dating, according to records.

She ultimately got the job. Nash denied being romantically involved with the applicant prior to the interviews, but investigators found emails and voicemail messages he left her before the interviews saying, “Just called to say I love you,” and “I want to hold you … I love you so much.”

The district determined Nash had lied to cover up the relationship and suspended him for 40 hours, records stated.

He then was accused of being disgruntled that the woman failed to obtain another manager position she had applied for. The man who got that job, Joe Ortega, complained to his managers in 2016 and 2017 that he was targeted for retaliation by Nash.

In an interview with The Times, Ortega said Nash refused to acknowledge him in social settings and coworkers broke off conversations with him when Nash entered the room.

In one instance, Nash showed Ortega and another worker video on his cell phone of himself shooting a gun, according to Ortega. Ortega and Nash then walked into a bathroom simultaneously, and Nash said to him, “can you imagine [the bullets] hitting skin?” Ortega said Nash told him he’d need “a lot of luck getting through this job.”

He said when he voiced concerns about Nash’s alleged intimidation, MWD officials accused him of exaggerating. An MWD spokeswoman said Human Resources officials “never accused Mr. Ortega of exaggerating or fabricating his allegations.”

Still, an investigation found that Nash acted inappropriately toward Ortega by refusing to speak to him and “setting a negative tone” for other workers, according to a heavily redacted copy of the investigative report provided by the district.

Nash was reprimanded by his managers and “counseled on appropriate management behavior,” according to the MWD spokeswoman.

Ortega said in February 2017 he took a demotion and a transfer to get away from Nash.

A manager close to Nash who declined to cooperate in a confidential investigation looking into the complaints, summed up the kind of problems many desert workers said they experienced.

“There is no confidentiality in the desert,” the manager, Hector Enriquez, told an official, according to MWD records.

Enriquez would not comment on the issue, saying he was admonished not to discuss a confidential investigation. He also defended Nash as a good man who’s “not here to give his side of the story,” but declined to elaborate.

In 2018, Alan Shanahan, president of one of the district’s labor unions, said he complained repeatedly to the head of human resources about Nash, who was a supervisor, including his excessive drinking and strange behavior. Shanahan asserted that the agency launched an investigation later that year only after he warned the official, Diane Pitman, that he would publicize Nash’s misconduct if he wasn’t fired.

A district spokeswoman disputed this account, saying specific reports of misconduct provided by the union and another employee prompted the investigation, but not any threat from Shanahan. The spokeswoman said that Shanahan had been “critical” of Nash previously, but “the information he provided was too general and insufficient to trigger action,” and he was encouraged to return with more concrete allegations.

The findings of the months-long investigation, summarized in Nash’s 14-page firing notice obtained by The Times, portrays him as a thrill seeker who disregarded rules about bringing guns and live ammunition to district property, drank on the job and recklessly endangered employees.

In one incident, as Nash picked up employees from a local airport he pulled the emergency brake on his vehicle, executing a dangerous “power slide” toward the airplane, records of the investigation said. An employee also complained that Nash said he wanted to crash his plane into his ex-wife’s house, workers said.

After leaving a management meeting in downtown L.A., Nash drove “fast and erratic” with another employee, pulled into a restaurant parking lot and almost struck another employee before coming to a “screeching halt,” the document said.

“Due to the hierarchy of men in the company, my father was able to ride on a ‘high.’ It’s harder to fight the current than it is to follow it, yes? I think he decided to follow the views of close-minded men and lost himself along the way.”

— Donald Nash’s daughter, Baily

Nash developed what many coworkers described as a peculiar obsession with a street sweeper, taking it out at odd times of the night and driving aimlessly around the camp for hours, they said.

On multiple occasions he crashed and damaged the vehicle, including a collision with a dumpster that was caught on video, the records and interviews show.

Lake Mead is just 39% full as critical negotiations between California and other Western states get underway.

He also allegedly misused MWD time and resources, including spending $8,000 in district funds to purchase a 3-D printer, according to the documents. Nash said the equipment was for work use. But he kept the printer at his house, and it was never barcoded and registered as a district asset, the firing notice said.

He organized a party trip on a company bus during work hours, traveling from Gene Camp at Lake Havasu to Dodger Stadium for a game. Nash told employees that “everyone would get really drunk before the game,” and called workers who declined to go or expressed discomfort about the trip “losers and party poopers,” records said.

Williams, the retired aqueduct operator, said he saw employees load “ice chest after ice chest” filed with alcohol into the bus before it departed. The group didn’t return until around 6 a.m. the next day, he said.

Meanwhile, district employees were growing increasingly worried that Nash had a potential for violence.

When Nash heard he was going to be suspended again in late 2018 pending the investigation into his behavior, he swooped so low over the Iron Mountain camp in his plane that workers could hear the engine roaring over them, according to Smith, who was the manager of the camp at the time.

“He got in his airplane and took off like he was running from the devil,” Smith said.

After he was placed on suspension, the district commissioned a threat assessment by an outside expert who concluded Nash posed no danger to employees or district property. Nash assured district investigators that he would not become “San Bernardino 2.0,” according to interview transcripts, referring to the 2015 terrorist attack that killed 14 people.

Shanahan said he pleaded with the director of human resources to have Nash removed from the district house where he resided because he kept a collection of guns and could take aim at people or valuable equipment. He said she refused. A district spokeswoman said Nash wasn’t removed because the threat assessment found he posed no danger.

In May, 2019, a district manager sued the MWD and filed a complaint with the state Department of Fair Employment and Housing alleging that Nash bullied and sexually harassed her between 2015 and 2018, and that the district did nothing to stop it despite her complaints. At the direction of MWD employee relations, she complained to her manager, the lawsuit said.

Council President Nury Martinez requested a report on the city’s relationship with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California after a Times article detailed a pattern of accusations from women who worked there.

The document says she sought and accepted a lower paying job at another facility to get away from Nash, only to be harassed by a manager there. The MWD denied the allegations in court documents. But as part of its settlement, the agency agreed to provide her backpay to cover the difference in compensation, according to a copy of the agreement obtained by The Times.

A district spokeswoman said a review done last year concluded that Nash retaliated against her.

About a week after the sexual harassment lawsuit was filed, the district notified Nash of its intent to fire him.

Meanwhile, despite the finding from the threat assessment, the district stationed 24-hour guards armed with concealed weapons at Gene Camp and contacted the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department because they “believe that Nash might cause harm to himself or others,”police records reviewed by The Times showed.

On July 15, 2019, the date Nash was scheduled to be moved out of his house, he was found dead at the home. He used a shotgun to take his own life.

Enriquez discovered the body, according to coroner’s records.

Nash’s daughter, Baily Nash, now 22, arrived at the house after her father’s death to collect his things. She described the scene in an email to The Times.

“The bathroom door was taped up with a white sheet of plastic,” she wrote, “and a small square of carpet cut out in the hallway leading to the bathroom.” The comic book film “Deadpool” “was playing in the bedroom to the right. Nobody bothered to shut it off,” she said.

Baily Nash questioned whether her father was a product of MWD’s “cut-throat” male-dominated culture.

“Due to the hierarchy of men in the company, my father was able to ride on a ‘high,’” she wrote. “It’s harder to fight the current than it is to follow it, yes? I think he decided to follow the views of close-minded men and lost himself along the way.”

Last year, Nash’s mother, Patti Venable, filed a wrongful death claim against the MWD, alleging that his suicide note implicated district officials in her son’s death. The note said he apologized for poor decisions he made that “caused disgrace on himself and his family,” according to a summary contained in the coroner’s report. He said he had felt abandoned and overwhelmed, and that he “has too much debt and alimony to retire without finishing his career at similar pay.”

MWD returned the claim, the precursor to a lawsuit, saying it wasn’t filed within the required time.

MWD board members told The Times that management never briefed them about Nash’s suicide, the circumstances leading up to it and his alleged misconduct.

i.

One board member, Adan Ortega, said he first learned of Nash’s death while visiting Gene Camp with other local politicians on one of the inspection tours board members regularly take to see how the facilities are performing.

He noticed police tape surrounding a house at the nearby Whitsett plant and asked the trip manager what had happened. He was told there was a death but the manager declined to share details, he said.

A district spokeswoman said the board isn’t briefed on such personnel matters because state law requires those discussions to be held in public, and the district wants to “protect the privacy of our staff.”

“We never heard a peep about it, before or after” the suicide, said Ortega, who was one of three board members to call for the independent review into sexual harassments complaints. “To be called by a newspaper about something this dramatic that happened at a work site, and not to know anything about it ... anyone who is a board member of any organization would be embarrassed by that.”

Sylvia Ballin, the mayor of San Fernando and the former board member whom Ortega replaced, agreed. Ballin is a former MWD employee who worked downtown and who knew Nash. She only found out about the suicide several months ago, and was never officially informed by the district, she said.

“It was a terrible way to find out what happened,” Ballin said.

John Murray Jr., chairman of a committee that oversees district personnel, also expressed frustration at a meeting on March 8 this year and called for a staff report on the death. He said Nash’s use of a gun on district property to commit suicide indicated “extreme risk” to other employees. He suggested the agency may need to implement new policies.

::

Joe Ortega said he was traumatized by his experience and has “recurring dreams” about his time in the desert.

The social isolation and other conditions began to change his personality. He felt he would “keel over and die” from the stress of working under Nash.

When he returned to his old job as a district warehouse worker in La Verne, he said he took a $30,000 pay cut.

“I went home so I could still be alive today,” he said.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.