Facing recall, Newsom discusses ‘unthinkable’ pandemic challenges and offers hope for future

The governor emphasized his administration’s work to respond to challenges that “made the unthinkable commonplace” over the last year and pledged to address deep-rooted inequities further exposed by the pandemic.

Assuring Californians that their deliverance from the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic is within sight, Gov. Gavin Newsom on Tuesday made an aggressive effort to rekindle faith in his ability to lead a state tattered by unprecedented lockdowns, economic devastation and enough political animus to nourish an effort to recall him from office.

Newsom emphasized his administration’s work to respond to the challenges that “made the unthinkable commonplace” over the last year and pledged to address the deep-rooted inequities further exposed by the pandemic as California emerges from the outbreak.

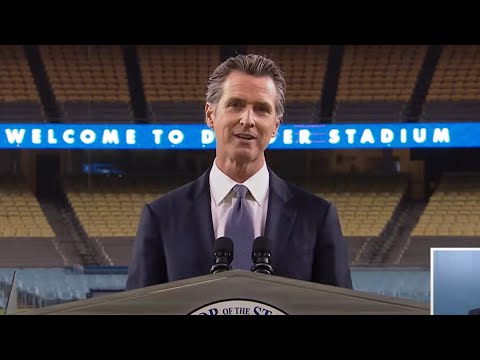

The Democratic governor delivered his annual State of the State address from Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, a mass COVID-19 vaccination site that served as a carefully staged backdrop for a speech laced with springtime optimism. Newsom noted that the capacity of the empty ballpark nearly matches the number of lives lost in California, symbolizing the toll of the pandemic.

“So tonight, under the lights of this stadium — even as we grieve — let’s allow ourselves to dream of brighter days ahead,” Newsom said. “Because we won’t be defined by this moment — we’ll be defined by what we do because of it. After all, we are California.”

Newsom said his administration “agonized” over the sacrifices Californians were asked to make to stem the spread of the deadly virus. But he said the vaccinations arriving daily and precautions millions have taken over the past year to save lives and reduce the spread will accelerate efforts to lift that burden — allowing people to return to work, visit grandparents and attend proms and graduations.

“There’s nothing more foundational to an equitable society than getting our kids safely back into the classrooms. Remote learning, it’s exacerbated the gaps we have worked so hard to close,” Newsom said. “In just a few short months since — working together with parents, teachers and school leaders — we’ve turned the conversation from whether to reopen to when. And that ‘when’ is now upon us.”

“So tonight, under the lights of this stadium — even as we grieve — let’s allow ourselves to dream of brighter days ahead,” Newsom said. “Because we won’t be defined by this moment — we’ll be defined by what we do because of it. After all, we are California.”

Newsom’s message comes as weary Californians commemorate a year of restrictions and closures that have frozen many lives in place, devastating businesses and putting millions out of work, postponing weddings and canceling school dances, isolating the elderly and forcing schoolchildren into distance learning programs.

The governor acknowledged the tremendous human cost wrought by the pandemic but for months has urged patience and caution, noting that the virus continues to claim hundreds of lives each day. Nearly 55,000 Californians have died of COVID-19, and 3.5 million have been infected, with Latino and Black communities throughout the state among the hardest hit. More than 7 million Californians have received unemployment checks since last March.

Newsom said California’s forceful response — it was the first to issue a statewide stay-at-home order last March — and sacrifices made by front-line workers helped to lessen the toll. California’s COVID-19 death rate is lower than that of more than half the states, including New York, Florida, Texas, South Dakota, Mississippi and Kansas.

The return to some semblance of normalcy could help Newsom’s chances of beating back an effort to recall him.

In a subtle reference to the GOP-led campaign to remove him from office, the governor said he wouldn’t “change course just because of a few naysayers and doomsdayers.”

“So, to the California critics who are promoting partisan political power grabs with outdated prejudices and rejecting everything that makes California truly great, we say this: We will not be distracted from getting shots in arms and our economy booming again,” he said. “This is a fight for California’s future.”

After nearly a year of distance learning, reopening schools has become a top priority for the governor with the potential for a recall election looming. Newsom and state lawmakers agreed to provide $2 billion in financial incentives to districts that offer in-person education to elementary students by April 1 under a law he signed last week.

Speeding up vaccinations is another key focus for Newsom, who touted the 10.6 million doses that have been administered statewide during a visit to Fresno on Monday. Newsom recently announced a short-term plan to allocate 40% of the state’s supply to disadvantaged communities.

Days after former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, a Republican, announced his intention to run in a recall election if the effort qualifies for the ballot, the governor shifted his media strategy and launched a campaign-style tour of in-person news conferences in major media markets throughout the state.

Newsom also convinced lawmakers to provide $600 state payments to low-income Californians. The “Golden State Stimulus,” which he signed into law in February, is part of a $7.6-billion economic recovery package.

Shortly after the onset of the pandemic, Newsom enjoyed soaring job approval ratings and praise for a decisive response, but those high marks began to deteriorate as time went on. Though Americans fed up with restrictions directed their frustrations at governors across the country, Newsom’s missteps drew national headlines.

Pictures of the governor sitting unmasked next to Sacramento lobbyists at a birthday party at Napa Valley’s French Laundry restaurant drew outrage in November, at a time when Newsom had advised Californians to avoid multifamily gatherings.

Local elected officials, county health officers and state lawmakers also voiced pressing concerns throughout the pandemic about a lack of communication from the governor before he announced major changes to business restrictions, vaccine tiers and other statewide policies that they said left their communities unprepared for the rapid shifts.

The governor’s decision to begin lifting the original stay-at-home order last May to allow indoor dining in some counties was met with praise by some and disapproval from others who felt he was caving to pressure from business interests. Within weeks, COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations had increased again, and Newsom faced criticism that he reopened too quickly.

Adding to the complications, the state’s Employment Development Department, which handles unemployment benefit claims for Californians, has been fraught with problems.

“I know our progress hasn’t always felt fast enough,” Newsom said. “And look, we’ve made mistakes. I have made mistakes. But we own them, we learn from them, and we never stop trying.”

Supporters of the effort to oust Newsom from office have seized on the missteps, and it appears likely they will gather enough voter signatures to trigger a recall election by year’s end.

Along with the pressure of responding to a deadly pandemic, Newsom now faces added scrutiny of his decisions and speculation over whether they are motivated by his effort to fight back against the recall effort.

Assembly Republican Leader Marie Waldron of Escondido accused Newsom of being all talk and offering little substance. She pointed to chronic delays in sending unemployment benefits to Californians who have been out of work and said Newsom did not have a coherent plan to reopen schools and business.

“The governor decided long ago to go his own way with handling COVID and the meager results speak for themselves,” Waldron said in a statement.

Republican political strategist Matt Rexroad compared the pandemic to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, saying it would be an extremely challenging crisis for any politician. Still, Rexroad believes Newsom’s missteps allowed many Californians to lose faith in him. Voters seemed to have more confidence in previous governors — including Republican Pete Wilson and Democrat Jerry Brown — in times of crisis, he said.

“I don’t think anyone doubted that either one of them could make the trains run on time,” Rexroad said. “I don’t know that Gov. Newsom gets that benefit of the doubt.”

Inside the wind-whipped Dodger Stadium Tuesday evening, it was eerily quiet as the sky darkened over the empty tiers. The absence of the pre-pandemic pomp and circumstance came into sharp focus as Newsom entered the stadium to the sound of about half a dozen people clapping.

One of the few inside was Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who made it clear he thinks Newsom will survive the effort to oust him from office. The mayor acknowledged, however, that people are frustrated, depressed and anxious for the pandemic to end.

“We could find 10% of Californians to be against sunshine right now,” Garcetti said.

No governor in modern history has faced more unexpected challenges than Newsom, who took the opportunity to remind Californians of the hope on the horizon.

“Since this pandemic started, uncertainty — well, it’s been probably the only thing that we can be certain of,” Newsom said. “But now, we’re providing a little more certainty. Certainty that we’re safely vaccinating Californians as quickly as possible. Certainty that we’re safely reopening our economy. And certainty that we’re safely getting our kids back into the classroom. All of which adds up to a much brighter future for our state. Because California, we’re not going to come crawling back. We will roar back.”

Times staff writers Julia Wick and Patrick McGreevy contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.