California’s My Turn COVID-19 vaccination appointment system riddled with flaws, officials say

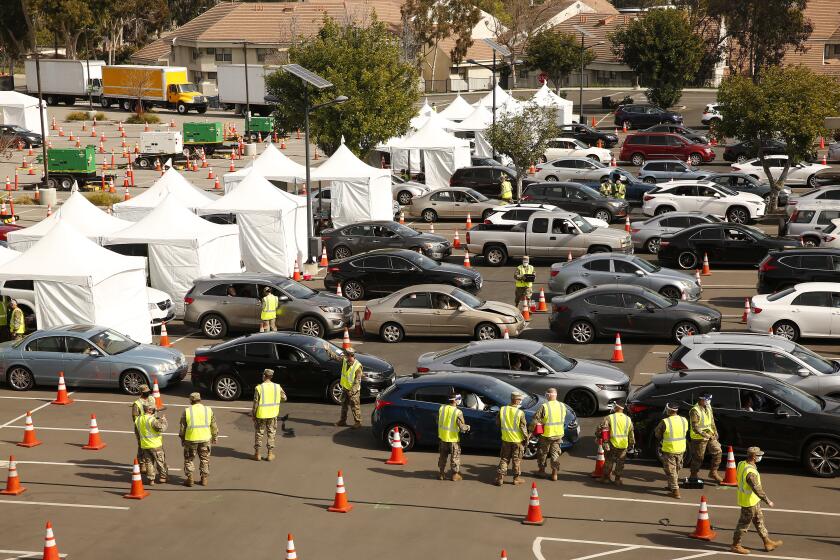

SAN FRANCISCO — California’s My Turn COVID-19 vaccination appointment system is riddled with flaws that are making it difficult for counties to reserve vaccine appointments for targeted populations, according to local officials.

These flaws have been exploited by wealthy, privileged people to use redistributed access codes to secure appointments for vaccines that had been intended for people living in underserved communities, as The Times has previously reported.

Though California is insisting that counties prioritize vaccinating people living in the hardest-hit areas or those who work in specific front-line essential jobs, the My Turn system does not offer the flexibility to account for a county’s vaccination strategy or eligibility requirements, Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Wednesday. It is also web-based, making it inaccessible for many who are unable to use an online interface, Ferrer added.

“My Turn is wide open and you can’t restrict access to appointments … to people who are in eligible categories,” Ferrer said. For instance, L.A. County sought to hold clinics at its so-called mega-POD (point of distribution) sites on Tuesdays and Thursdays just for food and agricultural workers, “but we really had no way to restrict people in making appointments in the system if they were eligible.”

The My Turn system also makes it impossible for the county to reserve appointments just for South L.A. residents for a vaccine clinic in South L.A.

At last week’s L.A. County Board of Supervisors meeting, Ferrer said some vaccine sites, lacking any good option, were forced to set up an alternative private registration system and then later enter the information into My Turn. On Wednesday, Ferrer said other solutions recently have involved enabling people to call the county’s call center to make appointments, while community vaccination sites have started to eliminate the need for online registration and mobile vaccine teams are helping to register people on-site.

“If we aren’t able to reserve vaccination options for our patients, we are very concerned that they’ll be pushed out by those with more free time, more resources, the ability to sit in front of their computer all day and the ability to drive anywhere in the county for a vaccine,” said Dr. Christina Ghaly, the county’s director of health services.

The state is working on improvements to the appointment system, Ferrer said, and she expressed hope that by the end of March people could easily make appointments by telephone if they don’t have access to a computer and the internet.

“But when it gets fixed, it’s going to have to allow for the variation that’s needed county by county,” Ferrer said. “I’ve talked with some counties, for example, where what they’d like to [do is] vaccinate farmworkers who are 50 and older before they vaccinate farmworkers who are younger, or because they have very limited supply. So you need a system that actually allows you to make your appointments that way, particularly since the state would like everybody to start using My Turn.”

Despite what the system allows, Ferrer asked that ineligible people not sign up for vaccination slots and said they will be turned away.

The problem isn’t the order in which people can book their appointments online. It’s the fact that people have to get online at all.

In a statement Wednesday night, Darrel Ng, a spokesman for the California Department of Public Health, said the state has a COVID 19 hotline (833-422-4255) with operators who speak English and Spanish to assist those who do not have access to the internet or who prefer to set an appointment over the phone. “Operators also have the ability to access a third party translator for an additional 250+ languages,” Ng wrote.

“This week, the state debuted single use codes on My Turn to provide precise targeting for clinics. It’s most notably being used to vaccinate thousands of teachers this week,” Ng added.

A breakdown in verification processes has been an ongoing issue in the state as vaccine eligibility has expanded. In February, some eligible caregivers to high-risk individuals were turned away at vaccine sites in L.A. County over fears that their legitimate paperwork was fake. The skepticism emerged after several ineligible people used forged documentation to try to jump ahead in the vaccine line.

Disability rights advocates hope that the state will hash out a simple verification process for the 4 million to 6 million disabled and sick residents ages 18 to 64 who become eligible for the vaccine March 15. Advocates hope that past issues will not prompt an overly cumbersome process for those who are less mobile or debilitated as state officials continue to formulate plans.

As vaccinations continue, L.A. County is continuing to see new daily coronavirus cases drop, although the rate of decline has softened. The county is averaging about 1,600 new daily coronavirus cases a day, a decline of about 22% from last week. But in mid-February, the week-over-week decline was 37%.

The county has administered more than 1.9 million vaccine doses, including more than 600,000 second doses. That means roughly 6% of the county’s population has been fully vaccinated.

State and local officials are continuing to implore people to wear masks and refrain from travel. On Wednesday, Ferrer said that of 679 specimens sent for genomic sequencing in L.A. County, 239 have been identified as being of the California variant, known as B.1.427/B.1.429; 27 of the U.K. variant, known as B.1.1.7; and one of the Brazil variants known as P.2. The county has not detected the other Brazil variant, P.1, or the South Africa variant, B.1.351.

Gov. Gavin Newsom also disclosed Wednesday that the first known case of the coronavirus tied to the New York variant, B.1.526, has been identified in the state — in Southern California.

“Our biggest worry is, of course, that people will relax too much, decide not to wear their face masks, decide not to keep their distance, decide to go back to having big parties. We’re just not there yet. None of that will be safe at this point, and all of it can cause spread,” Ferrer said.

With officials hopeful L.A. County in two weeks can exit the state’s most restrictive reopening tier, purple, which would allow the reopening of indoor restaurant dining, indoor gyms and middle and high schools with occupancy limits, Ferrer said recent data continue to show schools are not a major source for large outbreaks.

In February, only one new outbreak was detected at a school in L.A. County, Ferrer said. And of the 86 outbreaks affiliated with K-12 schools since September, only two involved more than 12 cases, and neither involved classrooms. (One site was open only to cafeteria workers, another was an office site that provided procurement services.)

Ferrer said it was imperative to continue driving down coronavirus case rates to allow more schools to open. Ferrer read some comments by students on the effect of the pandemic. “I have become distant with some friends since it is harder to see each other,” one read. “My mental health took a big toll on me and in January, my grandfather passed away, and because of the situation, we can’t hold a memorial for a couple of months,” said another.

“This pandemic has been extraordinarily difficult for so many,” Ferrer said. “This is why we really do need to recommit ourselves to use every single tool we have to reduce transmission, to vaccinate everybody who’s eligible, and to get to a place where all of our children can go back to school with the safety that’s required in the school community.

“Our children have been through something that none of us experienced as children. And we owe them all our support, and our effort, so that they can be as safe as possible.”

Times staff writer Julia Wick contributed to this report. Lin reported from San Francisco; and Money and Shalby from Southern California.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.