On New Year’s Eve, Dr. Marwa Kilani, the director of palliative care at a Mission Hills hospital, sat at home and filled out medical records for three patients whose lives ended just short of 2021.

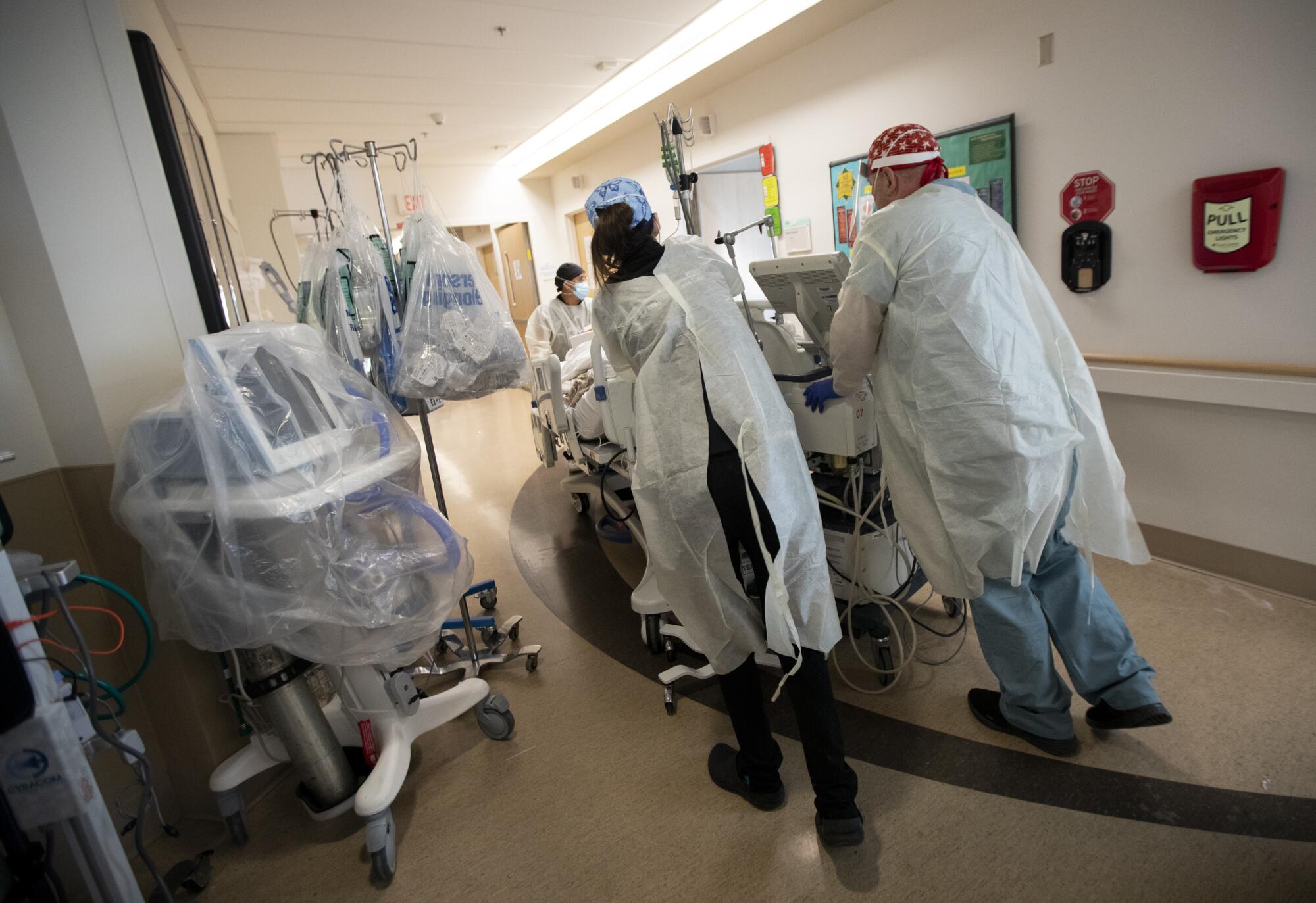

All were treated at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in rooms along the same hallway. They died Thursday from complications of COVID-19 within a few hours of each other. They were in their 60s and had been at the hospital for weeks — much of that time unconscious.

For Kilani, 47, the quick succession of deaths felt unbearably heavy. The deaths affected many in the ward, including the nursing staff and respiratory therapists who disconnected the patients’ ventilators.

“There’s an emotional distress that’s happening that you can’t put words to,” she said. “I am worried about the next few weeks. I’m scared and I’m scared for all of our staff — I worry for them. Nobody can seem to fill their bucket with good, positive energy.”

As 2020 drew to a close, an unprecedented surge of coronavirus patients was overwhelming medical facilities throughout Los Angeles County. Bodies were piling up at hospital morgues. Doctors were making difficult decisions about who received care.

In response, the county has allowed certain types of ambulance patients to be offloaded into the waiting room instead of the emergency room. Virtually all hospitals have been forced to divert ambulances with certain types of patients elsewhere during most hours.

Doctors such as Kilani struggle to take care of their own emotional health while also being a source of support for their colleagues, patients and patients’ families. But that’s becoming a more daunting task as the death count rises and hospital conditions worsen.

According to Kilani, Providence Holy Cross Medical Center is caring for nearly 200 patients with the COVID-19 — with more than two dozen in intensive care. While the main hallways are kept clear, some patients are being treated at the end of corridors, she said. The hospital has had to convert a recovery room into an area to treat intensive care unit patients.

Kilani’s colleagues know that much of the loss they experience is avoidable.

“I’m struggling more knowing that this level of death is preventable and that members in our community continue to get together,” said Katie Blake, a charge nurse in the progressive care unit at the Mission Hills hospital. “I’m acting as a stand-in to calm the fears of patients who cannot breathe. The look of fear in their eyes is enough to give someone nightmares. … It’s emotionally, mentally and physically exhausting.”

Before the pandemic, Kilani would meet in person with patients’ families to discuss expectations, spiritual care and symptom management. Now those challenging conversations are done over the phone.

That makes it harder to connect with families, and Kilani is sometimes left with a sense that relatives don’t trust the care doctors provide.

“A lot of it is because they can’t see their loved one — it’s the lack of visitation and the lack of ability to be present,” she said. “I totally get it and I understand how frustrating that is to be a family member and not be present with their loved one and hold their hand while they’re dying.”

But the doctor works to keep both families and her own staff uplifted.

Twice a week, she and a chaplain do “compassion rounds” where they meet with nurses to hear about the stresses of their days. While it can be difficult to come up with healing words, the meetings are an opportunity for the nurses to release some of their anxiety and perhaps talk about what they watch on TV or read as a distraction.

Kilani tries to cheer people up in small ways. On Christmas, she wore holiday-themed clothing and dangling gold earrings that looked like tree ornaments. On New Year’s Eve, she put on a T-shirt that says, “Where’s the Party” in big silver letters.

“I’ll try to do whatever I can to find humor, to get a smile,” she said.

But Thursday was particularly difficult. Kilani spoke on the phone with a patient’s family who had decided to begin comfort measures for their relative. That meant administering medication for pain and anxiety while letting the patient’s blood pressure go untreated — knowing that he would pass away.

The patient was a woodworker, and to try to make the family feel better, Kilani said she wished she had known them at a different time so she could appreciate his work.

“They thanked me,” she said. “They were grateful that we got to know him. They said he was remarkable.”

Within 10 minutes after she had hung up, the craftsman had passed on.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.