L.A. County’s spiking COVID hospitalizations are literally heading off the charts

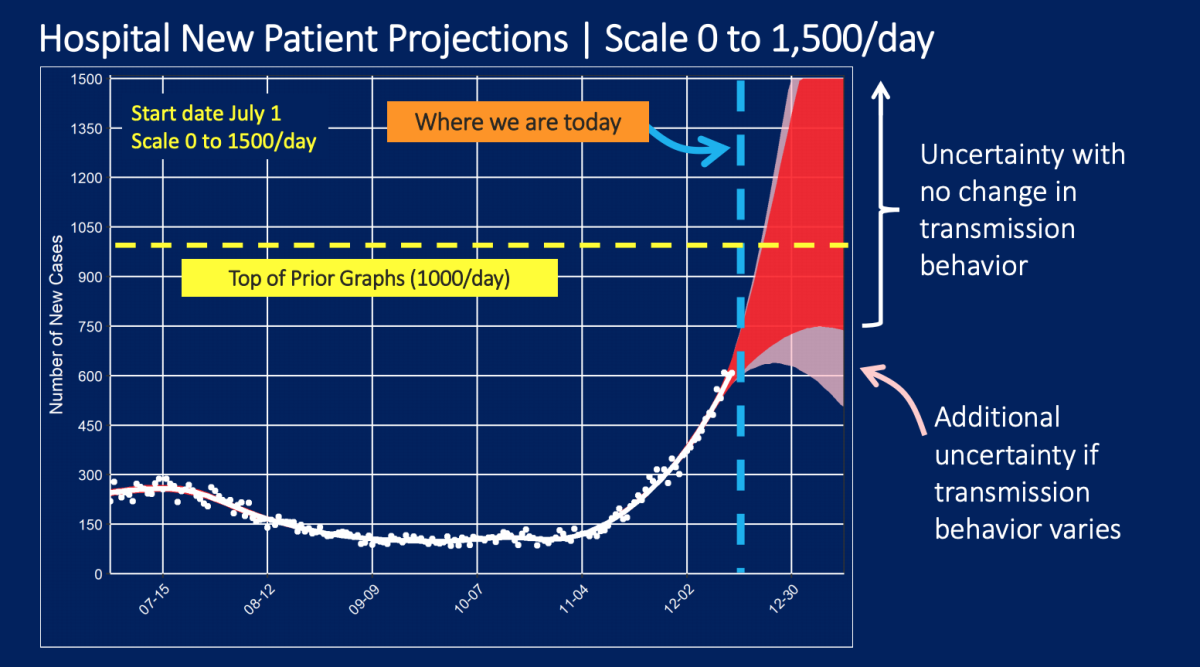

The pace of new COVID-19 hospitalizations is spiking so quickly in Los Angeles County that it is now literally off the charts, forcing officials to redraw the graphics used to illustrate the grim projections for what is ahead.

In October, fewer than 150 patients infected with the coronavirus were being admitted daily into hospitals.

By late November, that number had doubled to about 300 patients a day — as high as it’s ever been in the entire pandemic.

And now it has more than doubled yet again, to roughly 700 new hospital patients daily, just a few days before Christmas. That rate is bringing crisis to L.A. County.

If disease transmission behavior does not change, a projection issued by the county Department of Health Services says that L.A. County could be headed to between 700 and 1,400 new hospitalized patients a day by New Year’s Eve.

Daily COVID-19 hospitalizations could rise tenfold compared with October

“The model is suggesting that we could easily be seeing 10 times or more daily admissions than we saw in October,” said Dr. Roger Lewis, director of COVID-19 hospital demand modeling for the L.A. County Department of Health Services and a professor of emergency medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in West Carson.

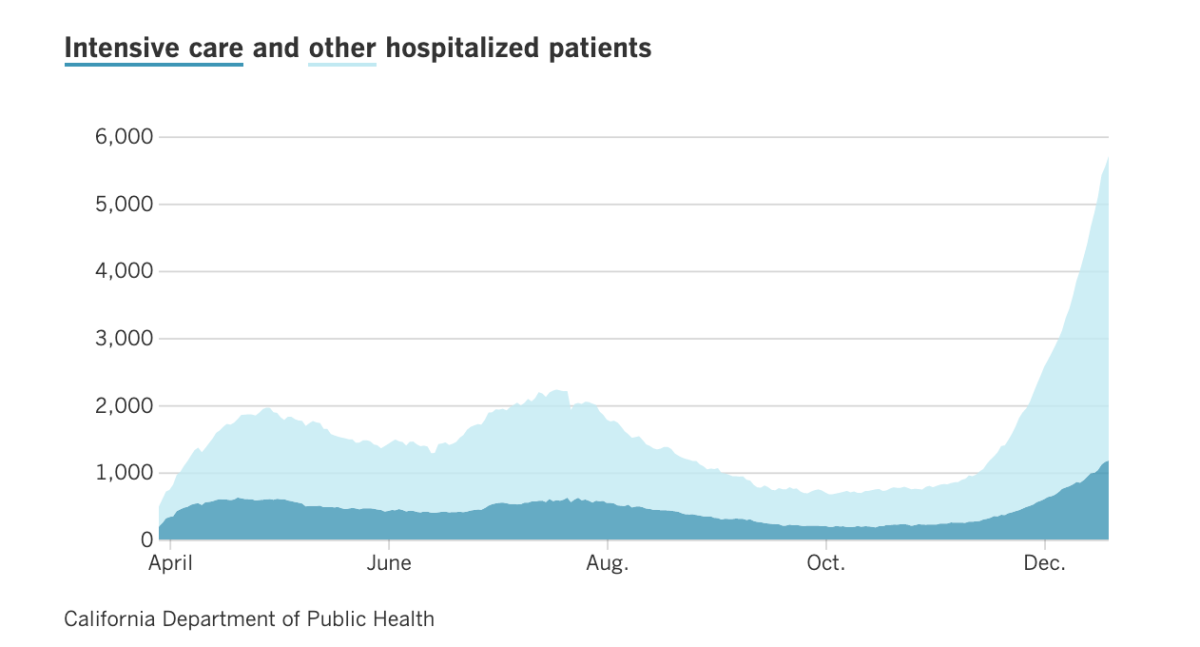

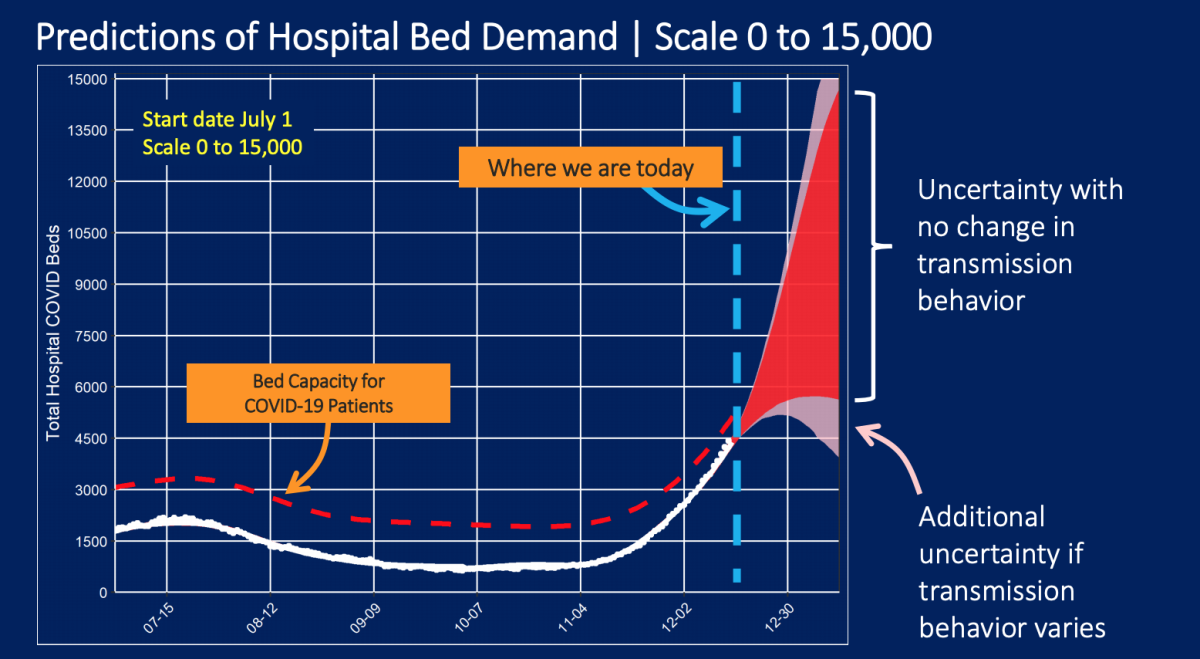

Already, the number of people in L.A. County’s hospitals with COVID-19 was nearly 5,900 as of Sunday — more than double the summer peak during the second wave of the pandemic, in which no more than 2,232 people were in the hospital with the disease on any particular day.

This means that by the end of the year, we could be seeing as many as 9,000 people with COVID-19 taking up L.A. County’s hospital beds.

And by mid-January, there could be 14,000 if there’s no change in transmission behavior.

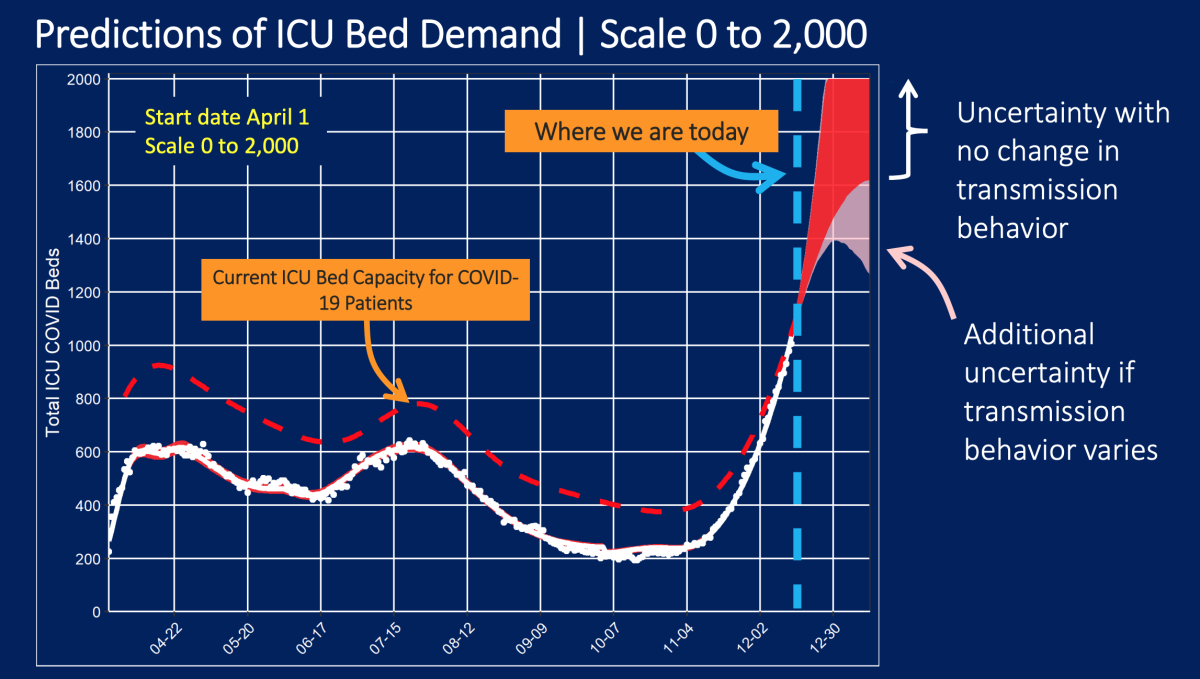

Particularly alarming is the chart showing the forecasts of intensive care unit demands.

‘We do not have available ICU beds’

Last week, L.A. County effectively ran out of available ICU bed capacity for COVID-19 patients — the first time that has happened in this pandemic.

“We do not have available ICU beds for additional patients right now,” Lewis said.

More than 1,200 COVID-19 patients in L.A. County were in the ICU on Sunday, more than triple the number from late November.

“Now, that doesn’t mean that the hospitals aren’t continuing to do everything they can to increase capacity. But there is there is a limit to what can be done,” Lewis said Friday. “I think the largest challenge facing hospitals in the next week or two is going to be the staff necessary to take care of patients with COVID-19, who require the higher levels of care.”

On Monday, Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said L.A. County is on track to record 110 COVID-19 deaths a day within weeks. The county is currently averaging 84 deaths a day.

So what are hospitals doing when there are no more available beds in the ICU?

Lots of options to deal with an ICU shortage — none ideal

Among the options to find ways to treat critically ill patients when the ICU is full:

- Asking nurses to take care of more ICU patients than usual. Normally, an ICU nurse cares for one or two patients at a time. It’s possible that nurses might be asked to care for three or four simultaneously.

- Placing critically ill patients in physical locations outside the ICU, like keeping them in the emergency room for longer. But “it’s not ideal to be in a physical location that was built for providing that level of care,” Lewis said.

“Having the system have to accommodate this increasing demand and do the best with what we have is not going to yield as good patient outcomes as we could achieve if we had a lower demand for care,” Lewis said. “Everybody is doing things differently than ideally we would like to do because there’s more patients than we can take care of.”

ICU availability in Southern California at 0%, and the crisis is expected to get worse, officials warn.

And that means patients are at risk of worse outcomes. “That includes longer lengths of stay in the hospital, longer lengths of time on the ventilator, and ultimately, mortality,” Lewis said.

When there are too many patients for available medical staff, there’s “just not going to be the same quality of monitoring,” said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, an epidemiologist and infectious disease expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Other temporary measures are not ideal. Keeping critically ill patients who need to be in the ICU waiting in the emergency room not only results in degraded quality of care, Kim-Farley said, but also creates a ripple effect that keeps patients waiting in ambulances for hours just outside the hospital. That leaves fewer ambulances available to respond to calls.

Concerns about exhaustion

Exhaustion is another key point of concern. Nurses are the ones at the bedside of ICU patients, and are now being asked to work in higher-intensity care settings than normal, taking care of more patients, “and they’re going to be asked to do that for weeks on end,” Lewis said.

So far, newly diagnosed coronavirus cases continue rising in L.A. County and statewide, to at or near daily record levels. That means the pace of infections that occurred over the Thanksgiving holiday and in the people who got infected from those people is still rising.

Eventually, a fraction of those people who tested positive this week will need hospital care — the state estimates about 12% of those testing positive statewide and 10% in L.A. County — and the average length of stay in the hospital is six days before recovery or death.

“So the system is going to be asked to care for even a greater number of patients than it is today for the next couple of weeks at least,” Lewis said.

Two to three weeks to notice a change in behavior

“If everybody today started being extraordinarily careful and transmission was markedly reduced, then the benefits of that — which would be tremendous — would start to become apparent about three weeks from now,” Lewis said Friday. “So during the rest of December, we expect to see ... higher hospitalization census and increasing challenges for the healthcare system to provide the best possible care to the most people.”

It can take generally about two to three weeks from the time someoneis exposed to the virus for them get so sick that they need hospitalization.

“What we have in our control is what happens in January,” Lewis said. “If we do the right things now, January can be ‘not worse’ than December. But if we continue to see transmission the way it has been in the last month or so, then January will be even worse.”

When might we see evidence that the stay-at-home order is working?

A big question is whether the regional stay-at-home order that went into effect for most Californians on Dec. 7 is working.

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist and infectious disease expert at UC San Francisco, said when COVID-19 lockdown orders went into effect in France, the United Kingdom and Spain, “it took about two to three weeks for the effects of the lockdown to kick in.”

So this week, Rutherford will start looking at daily case rates to see if cases are starting to flatten or perhaps decline.

Ferrer has said she would start to look at trends around Christmas to see if daily cases were starting to decrease.

It will take until around the time of New Year’s Day for the effect of the stay-at-home order to start being reflected in hospitalizations, Lewis said.

Kim-Farley said it’ll be essential for people to say no to social gatherings during the winter holidays. “Are you invited to a party? Just say no. Are you invited to friends for dinner at their house? Just say no. That way, when you need an ICU bed, the hospital won’t be telling you, ‘No.’”

Times staff writer Maura Dolan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.