During the pandemic, chaplains are a lifeline for inmates

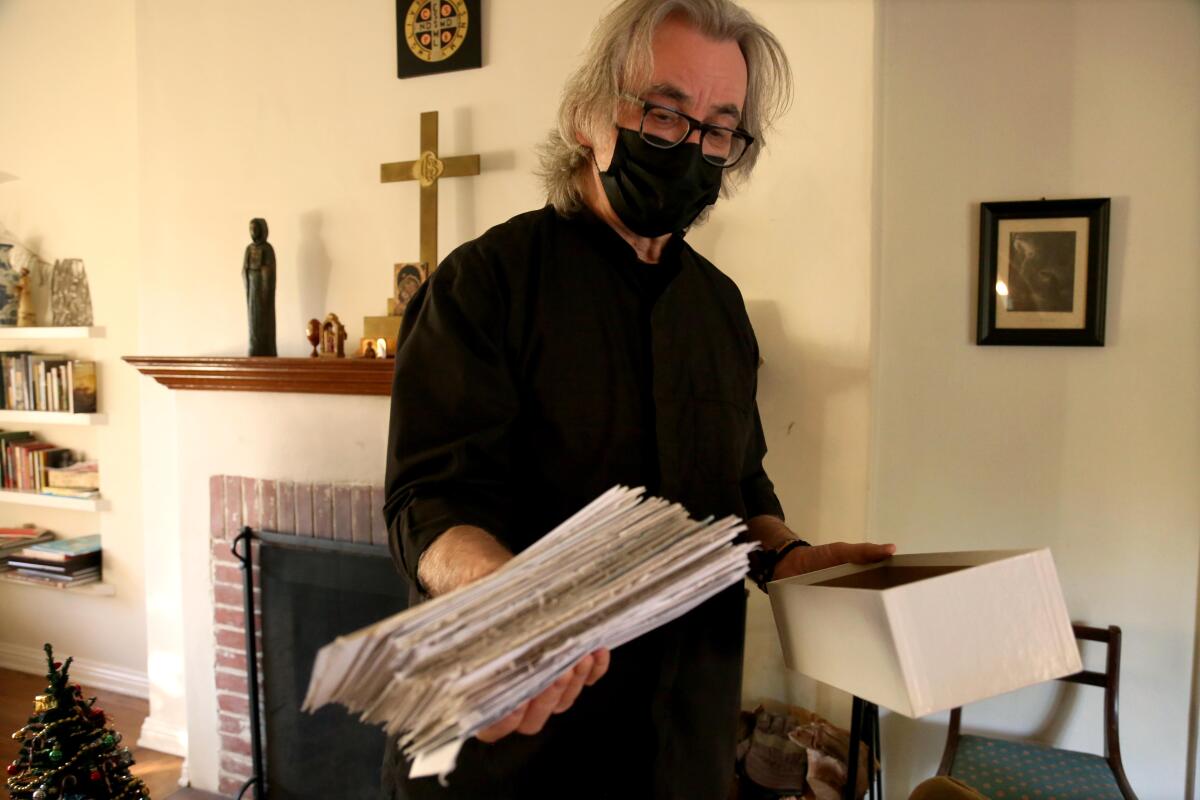

Every day, Brother Dennis Gibbs sits by a window in the living room of his monastery in the San Gabriel Valley and pens a letter or two to people behind bars.

His “friends on the inside,” as the gray-haired monk calls them, have kept up a growing correspondence with Gibbs for more than nine months, sharing an intimate view into life in jails and state prisons during the pandemic.

Many have voiced worry about the coronavirus and “the tenuous feeling of how it’s being managed in the jails,” said Gibbs, 66. They’ve admitted that some aren’t reporting symptoms for fear of being put in isolation.

Although sometimes left feeling powerless, Gibbs, who co-directs a restorative justice ministry of the Episcopal Diocese of L.A. and visited the county’s jails four days a week before the pandemic, has been uplifted by a surge in pen pals. He also circulates a newsletter he began in June for inmates that features spiritual reflections and inspirational quotes.

“Hopefully, all of this helps remind them that even if we’re not there physically we’re still there with them,” said Gibbs, who unlike some other chaplains decided not to enter the jails for fear of bringing the virus in. “There’s so much response, large and small, that says this is a lifeline.”

Since March, detention facilities have suspended public visits and quarantined those who may have been exposed to the virus, making an already stressful and lonely environment even more so. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which continues to deal with outbreaks, is also facing criticism for failing to protect inmates.

In L.A. County jails, and elsewhere across the state, chaplains say that they feel a greater responsibility to stay connected with inmates. They are writing letters, or if they can, visiting in person, aiming to bring companionship and hope at a time when inmates are concerned about their safety and that of their families — and suffer directly from the virus’ fatal toll.

“Sometimes they’ll ask us, ‘What’s going on on the outside? How bad is it really out there?’” said Frank Mastrolonardo, 64, a Protestant chaplain in the L.A. jails and founder of a nonprofit prison ministry. “Many times, we’ve calmed their hearts because they think everything has been falling apart at the seams.”

In L.A. County, chaplains and spiritual volunteers have continued to walk jail floors with carts of religious material and “have been deemed essential” during the pandemic, Sheriff’s Department spokesman Lt. John Satterfield said. It’s a stark contrast with other counties that have instituted harsher restrictions. In Fresno, chaplaincy visits have been put on hold. In San Bernardino, two contract chaplains may visit inmates but hundreds of religious volunteers cannot.

The Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which is starting to roll out video visitation with the public in prisons, allows chaplains to conduct individual counseling. It has also been providing virtual religious programing, including sermons broadcast throughout the week.

At a Kern County prison last month, one Jewish chaplain brought a kippah to an older inmate whom he believed had requested to be on suicide watch in an isolated cell because he was terrified of getting infected in a dorm.

“When he saw me, he just smiled,” said the rabbi, who requested anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak to reporters. “To acknowledge he’s not alone in fear and how he feels in general, that’s all we can do.”

Sgt. Alex Gamboa, who works in the Religious and Volunteer Services unit for the L.A. County jails, said he’s seen an increase in requests to see a chaplain. More than 100 chaplains and spiritual volunteers are active, Gamboa said. In November, chaplains logged more than 6,000 mostly one-on-one visits with inmates, often meeting multiple times with the same person. They’ve also hosted small communion services.

“It never stopped,” Gamboa said of the chaplaincy. “They’re really needed inside right now.”

The Archdiocese of L.A., for example, which employs eight jail chaplains who visit inmates regularly, has reported a rise in individual counseling. Gonzalo De Vivero, director of its Office of Restorative Justice, said these sessions shot up from 342 in February to 2,550 in October.

Part of the reason, he said, is that chaplains spend more time walking cell rows to offer counseling now that they’re no longer holding large Masses. That in turn has made inmates more comfortable speaking with the chaplains to ask for a prayer, books or a rosary.

Chaplains have helped console inmates who have lost family members to the virus.

Eve Ortiz, one of the church’s chaplains, spends an average of three to 10 minutes per inmate at the Century Regional Detention Facility women’s jail in Lynwood, where she works five days a week. A few months ago, she counseled a woman in her 20s who said several close relatives had died from the virus.

Ortiz, 62, listened and then shared her own family’s story of grief and resilience. She told the woman that her mother survived the loss of three sons and lived to be 91 while still keeping her faith.

“I could see her snapping a little bit out of her grief for me to empathize with me,” Ortiz said. “We sort of put ourselves on the same level.”

When deciding whether to continue visiting the jails, Mastrolonardo, the Protestant chaplain, said he reflected on a letter that Martin Luther, the father of the Protestant Reformation, wrote when a plague hit his town of Wittenberg, Germany. Luther had said that he would fumigate, help purify the air and avoid places where his presence was not needed, but that he would go to a neighbor in need.

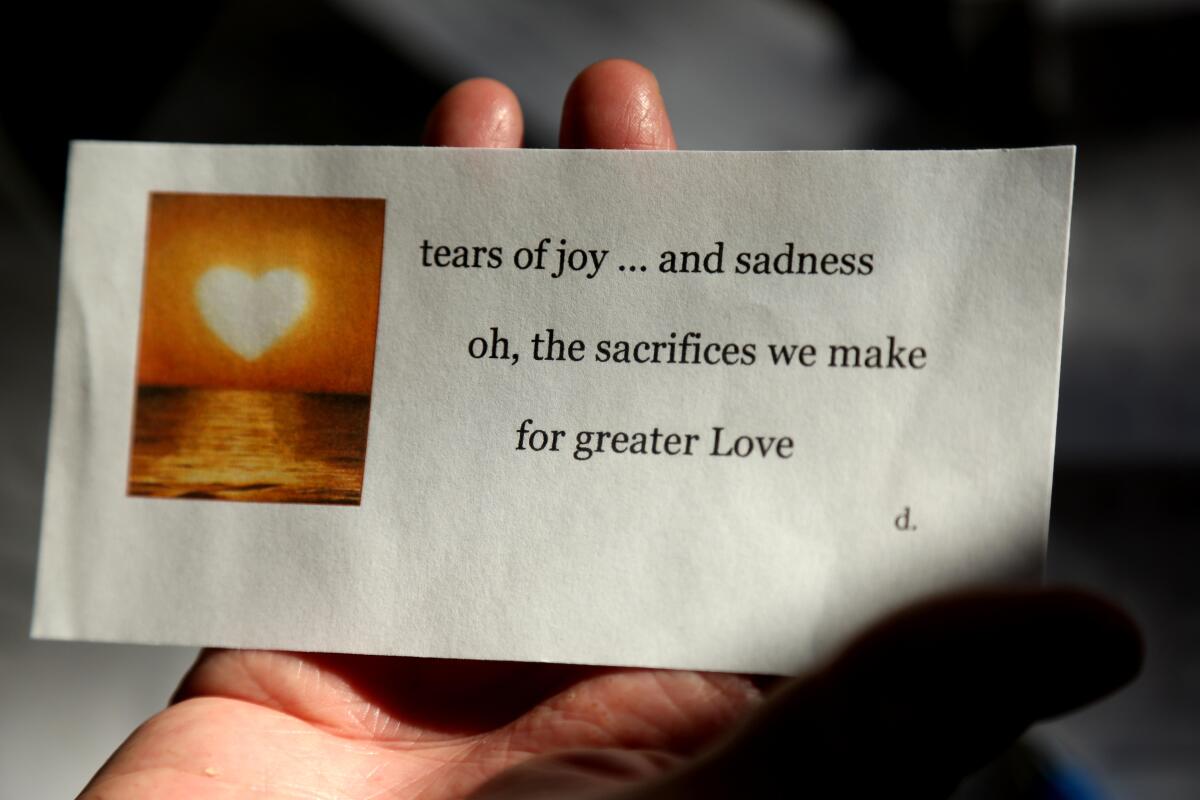

His ministry has distributed 30,000 cards to the jails, giving them to inmates to mail to their loved ones.

“People were flying out of their bed,” Mastrolonardo said, describing the enthusiasm as a group of chaplains and volunteers had walked by the dorms at North County Correctional Facility in Castaic to distribute the cards.

Like Ortiz, he’s comforted inmates who have suffered losses.

“I’m seeing a lot of broken men and women behind bars who haven’t had any visitations, no yard time in some cases,” Mastrolonardo said. “They have family members dying on the outside. Who is the one who is going to give them death notifications? It’s the chaplains. Who is going to go and counsel? It’s the chaplains.”

Some former inmates say chaplains made a lasting difference.

Laurence Roth, a 31-year-old resident of North Hollywood who was discharged from an L.A. County jail in March after serving about four months, recalled how he had not received visits because his then-girlfriend had been homeless and couldn’t get in touch with him and his family lived on the East Coast.

Roth said that his life was transformed when he heard Mastrolonardo one day preach about the forgiveness of sins. The chaplain would sometimes visit him twice a week through the bars, he said.

“It was so special for me because I had nobody,” said Roth, a former drug addict who now works at a church and plans on becoming a pastor. “My life was falling apart…. What they [the chaplains] offered me was relief from the guilt.”

Chaplains now ministering through letter-writing have maintained strong connections to inmates too.

Sister Greta Ronningen, who lives at the monastery with Gibbs and co-directs the restorative justice ministry, said that inmates are often exposed to trauma, loss and abuse, and that “there’s a deep desire to get right — with their families, themselves, with God.”

She received a letter around Thanksgiving from a woman at a youth correctional facility in Camarillo. The woman had been looking forward to Thanksgiving week and was devastated because her dorm had been quarantined after a positive case of the virus.

Ronningen immediately ordered her materials on Amazon, including a teen novel and a daily meditation on self-worth, to cheer her up.

“Everyone knows it will end, it’s just holding on and getting through it,” she said of the pandemic.

On a recent afternoon, Gibbs sat down at the monastery to respond to several letters. On his writing table lay a notebook for logging his correspondence and paper cutouts with inspirational messages and haikus to slip into envelopes.

An inmate from Valley State Prison had sent him a commitment to become a “divine companion” of the monastery, joining a program in which inmates agree to follow certain principles, such as nonviolence, and build a relationship with the monks.

Gibbs had written him six letters throughout the pandemic. In the letter the monk opened, the inmate voiced his gratitude, saying that Gibbs had once saved him from potential suicide.

“I’m glad I came to your church service that day because I may have killed the wrong person,” he wrote. “I cry every time I think about that moment in time. I never want to forget it because it helps me stay humble now. It saved my life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.