L.A. County moves to create new juvenile justice system focused on ‘care,’ not punishment

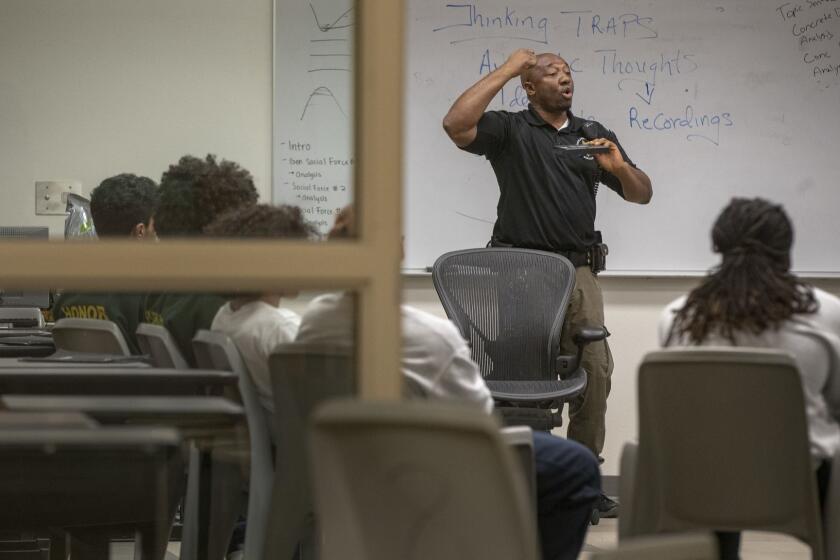

After years of incremental reform, Los Angeles County is moving to dismantle the largest youth justice system in the country in favor of a “care-first” model that would look less like prison and would emphasize emotional support, counseling and treatment.

The plan calls for children and young adults who have committed crimes to be served in home-like settings, and includes 24/7 youth centers and support teams that establish relationships with young people who might otherwise be locked in facilities far from home.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday took the first steps to transition juvenile probation to a proposed new Department of Youth Development, in a three-phase approach that will take at least five years. Similar approaches have been tried in San Francisco; Houston; New York City; King County, Wash.; and Oregon.

When Lee Seale became Sacramento County’s chief probation officer in 2013, officials at his juvenile hall were grappling with how to prevent probation officers from using force against young detainees after multiple lawsuits, the resignation of a prior leader and a judge’s decree.

Supervisors Sheila Kuehl and Mark Ridley-Thomas said in their motion that, despite the board’s best efforts to reform a system plagued by controversy and abuse investigations, it has become clear a new approach is required.

“The current youth justice model in the county remains hyper-focused on punishment and forced accountability because that is simply the nature of any model rooted in the principles of probation and law enforcement systems,” the supervisors said in their motion.

Interim Chief Probation Officer Ray Leyva, who was unavailable Tuesday for an interview, said in a letter to the board that he rejected the notion by advocates who he said want to “defund and discard” his agency and have focused much attention on its past weaknesses, rather than its “track record of recent reforms.”

He said there are substantial challenges ahead in carrying out the overhaul that youth advocates want to see, including a lack of county housing options and the lack of a robust network of community services and supports.

He also raised concerns about redirecting “substantial work from dedicated and committed county staff to private agencies, without sustainable infrastructures.”

The union that represents about 3,400 detention service officers has similar concerns.

Hans Liang, president of the AFSCME Local 685 union, said his hope is that the county supervisors make good on their promise that his union’s members would have first dibs on jobs in the Department of Youth Development. Many probation officers already have advanced degrees, such as master’s of social work, he said.

Liang said he hopes to see the supervisors create a “hybrid type” model, creating a youth development division within the probation department, rather than a new agency.

Young people in custody need to be held accountable for their actions, but it’s equally important that they receive treatment and rehabilitative services to ensure they can be successful adults, Liang said.

“Within the current framework, we can create those specific outcomes and specific models that are being advocated by these youth groups,” he said.

The county’s Probation Department has been plagued in recent years by scandal and abuse investigations.

A Times investigation last year found that, as use of pepper spray by officers on children and young adults in custody has spiked in recent years, prompting recent calls for reform, so too have on-staff assaults.

The detention officer’s email described “chaos” inside one of Los Angeles County’s juvenile halls.

In 2004, the county Probation Department was put under federal oversight after a U.S. Department of Justice investigation revealed unsafe and abusive conditions in its juvenile halls. Four years later, a similar investigation found widespread civil rights violations in its then 19 probation camps.

Since then, the Board of Supervisors has worked to shrink the juvenile justice system. About 500 young people are being held in the county’s locked facilities, including two juvenile halls and six probation camps, according to Kuehl’s office.

Kuehl, who has two years left in her term, said that if it were up to her, the majority of young people in custody would not be kept in locked facilities.

“Now, we will always have young people that need to be isolated from the community because they’re dangerous and it’s [best for] public safety,” said Kuehl, who isn’t planning to run for reelection. “So, there will be locked facilities, but I don’t believe that we want to see them look like prisons with barbed wire.”

Youth advocates point out that the system includes startling inequities. Black youth in L.A. County are over six times more likely to be arrested and 25 times more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers, according to California Department of Justice data analyzed by county researchers.

And the children and young adults in custody often have serious mental health issues, further complicated by significant childhood trauma, including physical, emotional and sexual abuse.

Over the next several months, county officials must determine how the new department would be created and financed, and whether any state laws would keep the county’s plan from moving forward.

The plan approved unanimously by the supervisors Tuesday calls for a gradual wind-down of the probation department’s juvenile operations and an initial $75 million investment in the Department of Youth Development in the next county budget, which is approved in June.

A new mentality is needed to better serve young people in custody, the supervisors said in their motion.

“The county must resist a narrative about these young people that does not leave space for hope and healing, and insist on a structure that promotes positive youth development and rehabilitation at all costs,” Kuehl and Ridley-Thomas wrote.

Ridley-Thomas later said it more bluntly: “Our youth can’t get well in a cell.”

Times staff writer Matt Stiles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.