What are foehn winds? Fires in the Eastern Sierra were fueled by Santa Ana-like gusting

Strong southwesterly downslope winds fed fires in the Eastern Sierra last week, including one that devastated the town of Walker, near the California-Nevada border.

Winds gusted to 40 mph for 12 to 16 hours, according to Marvin Boyd, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Reno.

Like Washoe Zephyrs, the winds that fanned the Pinehaven and Mountain View fires, blew from west to east. But that’s where the similarity ends.

Washoe Zephyrs, described by Mark Twain in “Roughing It,” are westerly winds that are almost a daily occurrence on the eastern side of the Sierra during the summer. Washoe Zephyrs usually arise in the late afternoon and evening and gust at about 20 to 30 mph, kicking up dust across the arid landscape.

The destructive winds in the Eastern Sierra last week were foehn winds. California’s best-known ill winds, the Santa Anas, are also foehn winds, but they blow downslope in the opposite direction, from the northeast toward the southwest. The Diablo winds and Mono winds are also foehn winds, coming from the same direction. These are often referred to as offshore winds. Mono winds, which barrel down the western slopes of the Sierra from the area around Mono Lake, were implicated in the massive Creek fire in Fresno and Madera counties.

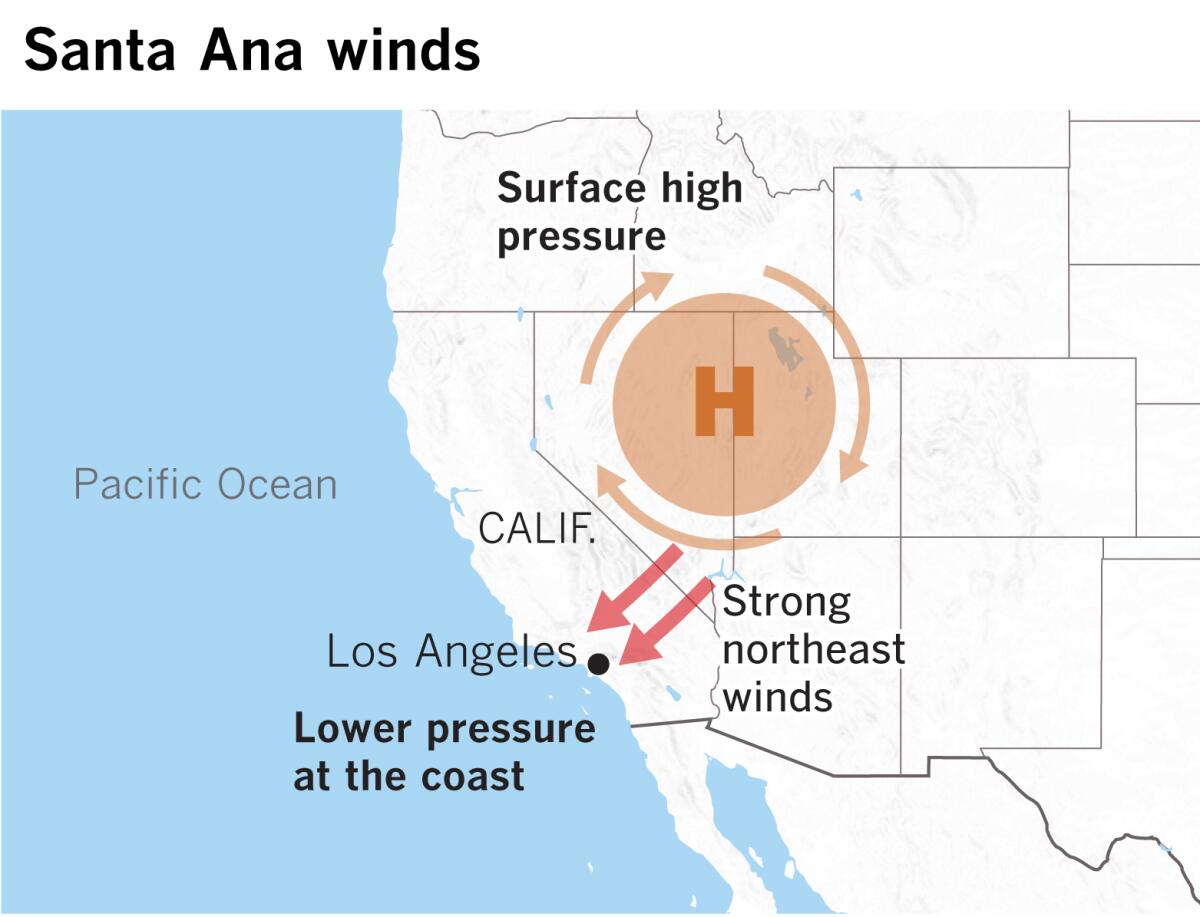

Santa Anas, Diablos and Mono winds have a common source: high pressure in the deserts to the east.

Moderate Santa Ana winds are expected to again visit Southern California, bringing low humidity and elevated to critical fire weather conditions though the Thanksgiving holiday weekend.

Last week’s wind event in the Eastern Sierra created “pretty remarkable wind-driven fires that show the power of the wind in November,” said Alex Hoon, an incident meteorologist, also with the National Weather Service in Reno. Multiple destructive wildfires were spread by winds that were “like a freight train,” he said. “Winds of this magnitude are uncontainable.”

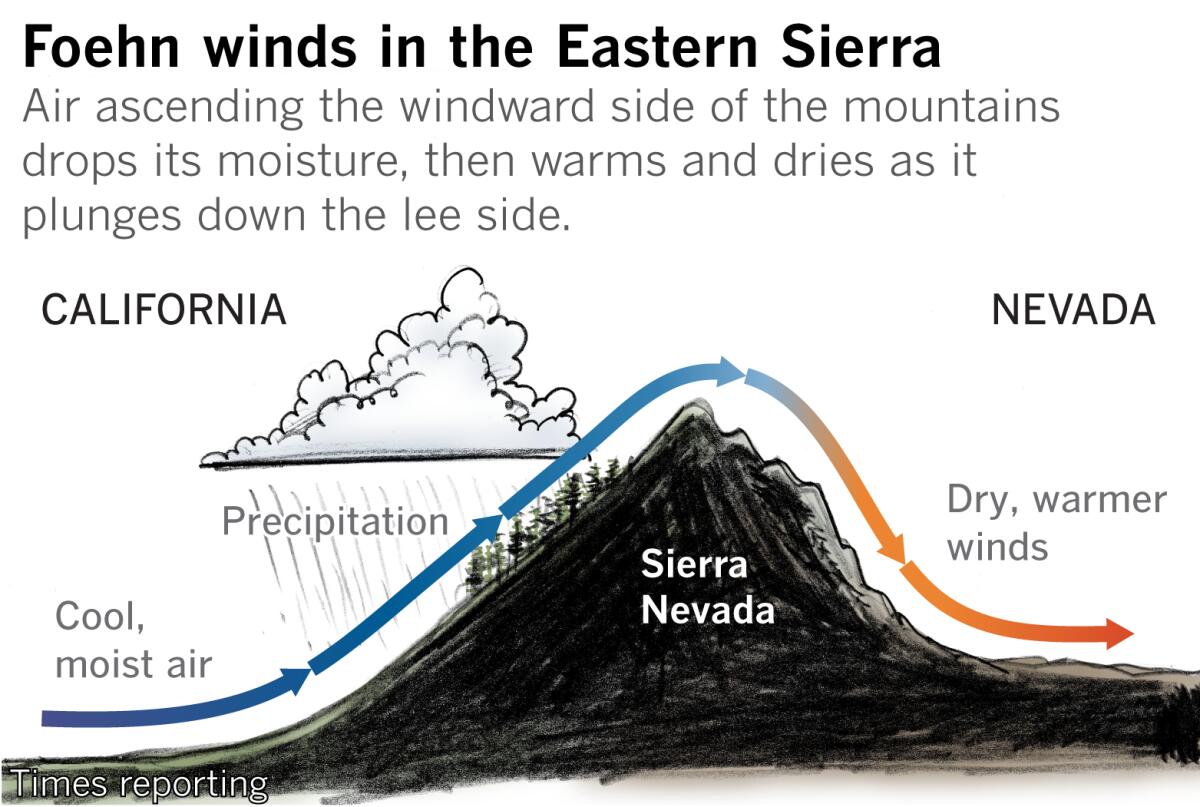

A foehn wind is defined as a strong, warm, dry wind that flows down into the valleys when stable, high-pressure air is forced down the lee slopes of a mountain range, according to the National Wildfire Coordinating Group.

As the air was lifted up the windward side and passed over the summit of the Sierra Nevada, the moisture in it was wrung out in the form of precipitation.

The air then descended and was warmed — at a rate of about 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit per 1,000 feet — and dried, producing critical fire weather conditions as it hurtled toward the California-Nevada border.

That flow was supported by a low-level jet stream, Boyd explained. A stable, pre-frontal layer of air over the top of the mountains was in just the right spot, forcing the winds downslope.

The strong winds and low humidity acted like a bellows on the fast-moving, plume-dominated Mountain View fire that consumed more than 28,000 acres and burned about 90 homes in Walker, jumping from home to home and forcing frantic evacuations, and resulting in a fatality.

When the incoming weather front arrived the following morning, it brought rain and snow that doused the fires.

Strong downslope foehn winds often disrupt the atmospheric conditions necessary for formation of pyrocumulus clouds like the one that developed with the Mountain View fire, and very strong winds tend to bend the plume more horizontally than vertically, according to Nick Nauslar of the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho. But, in rare cases, a pyrocumulonimbus cloud can form in spite of strong winds, as was the case with the Bear fire, part of this summer’s North Complex fire in Northern California, he said.

In the case of Southern California’s Santa Anas, the high-pressure air is usually pooled in the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah, and winds blow downslope toward lower pressure at the California coast. As they drain toward the coast they speed up as they funnel through passes and canyons, seeking a route of least resistance.

Foehn winds occur in a number of places around the globe. Chinook winds are a well-known example. They occur on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains, and also blow from west to east, producing dramatic changes in temperature and weather. Chinook winds, which can gust up to 80 mph, are called “snow eaters” because they can vaporize snow before it has a chance to melt. This process is called sublimation. The air is so dry that the snow goes directly from its frozen state to vapor — evaporation that bypasses the liquid or melted state entirely.

For Boyd, the weather service meteorologist, even though the Reno area had just received 6 inches of snow a few days before the winds kicked up, the Eastern Sierra infernos provided a dramatic illustration of how dry fuels and low humidity with extremely strong winds can make an explosive combination.

But while Walker is at about a 5,400-foot elevation, and Reno is at about 4,500 feet, Santa Ana winds descend mountain slopes all the way to sea level in Los Angeles, allowing for that much more compression heating and drying. That’s why Santa Ana winds can make you feel like you’re being blasted with an electric hair dryer.

Over Thanksgiving weekend, winds are expected to peak Thursday night and Friday morning, according to the National Weather Service, with critical fire weather conditions into Friday evening. By Friday morning, relative humidity in the L.A. area will be as low as the single digits.

Very dry air and fire weather concerns will linger through Sunday.

This time of year, the air mass in the Great Basin starts off much cooler, so temperatures won’t reach the 90s as they might with Santa Ana winds earlier in the season, said Rich Thompson, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Oxnard. But readings in the 70s and lower 80s are possible in coastal locations as the Santa Ana winds subside.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.