As coronavirus cases surge again, ICE leaders push to detain more immigrants

At a federal court hearing last week, Moises Becerra, a top official with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, discussed a plan to safely repopulate the Mesa Verde immigrant detention facility in Bakersfield. Over the summer, a COVID-19 outbreak had spread to more than half of the detainees and a quarter of the staff.

Now, against the backdrop of the latest and potentially most difficult wave of coronavirus cases across the state and country, ICE officials are pushing to increase the number of immigrants detained in California.

At the same time, advocates are urging California leaders to stop transfers from state prisons and jails to ICE custody and exercise public health oversight.

“We do not expect ICE to ensure compliance, therefore it is the responsibility of our state and local officials to address this humanitarian crisis,” said Jackie Gonzalez, policy director at Immigrant Defense Advocates.

In August, U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria issued a restraining order barring new detainees at Mesa Verde, mandating a population reduction to fewer than 50 and ordering weekly testing of remaining detainees and staff. The facility has space for 400 and is divided into four dormitories.

Lawyers for ICE have argued that because there have been no new cases and all detainees who had tested positive have since recovered, the court order is no longer needed. Two staff members tested positive last week, according to court documents.

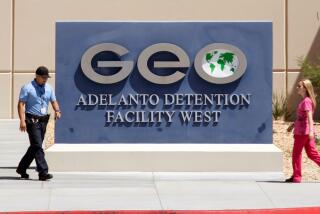

Immigrant advocates filed lawsuits in response to conditions inside five of the facilities in California during the pandemic. In the case of the Adelanto ICE Processing Facility, northeast of Los Angeles, a judge is still considering detainee bail applications to reduce the facility population. This month, the Otay Mesa Detention Center in southern San Diego County experienced its second coronavirus outbreak.

At Mesa Verde, ICE’s plan involves offering tests to all incoming detainees and placing them in quarantine or isolation for two weeks. Detainees who refuse tests will be quarantined separately. Detainees who test positive at intake will be isolated.

ICE spokesman Jonathan Moor declined to comment on pending litigation. A representative for GEO Group, the Florida-based company that manages three of the detention centers in California, declined to comment.

Becerra told the court that facility leaders are in the process of combining dorms in order to leave two empty to accommodate new detainees. Chhabria appeared unconvinced that the plan was strong enough to prevent a future outbreak.

“What happens if you have detainees in all four dorms and you have another outbreak?” the judge asked. “How do you start isolating people who tested positive?”

Though not written into the plan, Becerra said, the goal is to always have a dorm available. If not, new detainees would be sent to another facility.

But lawyers for ICE wrote in court documents this month that the agency should be allowed flexibility instead of being subject to a court order that “locks in how they might use their housing units.”

Lawyers for the American Civil Liberties Union and the public defender’s office of San Francisco are urging Chhabria not to remove the restraining order.

Emails disclosed recently as part of the court case indicate that Mesa Verde officials ignored protocols issued by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and misled the judge about their safety practices. Emails between ICE officials and the facility warden, Nathan Allen, show they waited four days to offer testing to a dorm that had been exposed to someone who tested positive July 31, despite having rapid-result tests on-site.

ICE officials also misrepresented certain facts, documents indicate. In a May 27 declaration, San Francisco Assistant Field Office Director Alexander Pham said all new detainees arriving from another facility with reported coronavirus cases would be placed in isolation for two weeks before being released to the general population. Lawyers later submitted a “notice of errata” to the court acknowledging that isolation is limited mainly to those arrested off the street or returning from being hospitalized.

Previously disclosed emails found that Mesa Verde officials rejected a suggestion to test all detainees there because it would be difficult to quarantine those who tested positive. ICE tested no detainees with COVID-19 symptoms before the outbreak started July 29.

While ICE tries to regain control of Mesa Verde, advocates are pushing for state leaders to require that the agency coordinate with local public health departments and stop transfers from state prisons and jails. They compared the need for intervention to instances in which state health officials took control of troubled nursing homes early in the pandemic.

In response to the pandemic, ICE released a set of requirements for detention centers, including the need to comply with state and local public health plans and coordinate with public health authorities to develop a COVID-19 mitigation plan.

Five of the six facilities in California are run by for-profit companies, and planned expansions could bring their combined capacity to 7,200. Coronavirus infections have been reported at each of the private facilities, including an outbreak of more than 150 people at Otay Mesa that at one point was the largest in the country and led to the first coronavirus-related death in ICE custody.

Immigrant advocate groups including the nonprofit Immigrant Defense Advocates asked public health authorities in counties where each of the six ICE facilities are located about their communication with facility operators.

According to a policy brief released this month, most of the public health departments said they hadn’t developed a COVID-19 plan for the facility in their jurisdiction. In an email response Sept. 9, Matthew Constantine, Kern County’s director of public health services, said the department “does not have jurisdiction within a federally contracted detention facility.”

Kern County officials said they met with the California Department of Public Health to discuss the outbreak at Mesa Verde on Aug. 24 — the same day advocates sent their inquiry and more than three weeks after the outbreak started.

ICE’s pandemic response requirements note that the agency must comply with the CDC’s interim guidance on COVID-19 in correctional and detention facilities. That guidance states that local public health officials should be contacted before an incarcerated or detained person who has a confirmed or suspected coronavirus infection is released.

Public health officials in Kern and San Bernardino counties said they had not received notifications.

Other documents showed facility leaders refused to cooperate with public health authorities. In an email exchange May 19, San Diego County Public Health Department epidemiologist Adriana Villasenor recommended to Assistant Warden Joseph Roemmich that all Otay Mesa Detention Center staff get tested.

Villasenor said the California Department of Public Health “is more strongly urging facilities with outbreaks to employ this to get a good baseline of asymptomatic staff and residents (to help mitigate spread).”

Roemmich responded, “Just so we’re clear — at this point we have no intention to mass test our staff.”

At a California Senate hearing Thursday about COVID-19 in state prisons, ACLU attorney Monika Langarica said prisons and jails supply most ICE detainees in California. She argued that those transfers are voluntary and endanger the community during a pandemic.

“Without constant intervention from all angles possible, more people may die in ICE detention,” she said.

But Heidi Dixon, chief of case records services for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said the agency is required under state law to notify ICE of foreign-born inmates, allow ICE officials to enter its facilities to interview inmates, and facilitate transfers to ICE custody.

California law says the department of corrections shall cooperate with immigration authorities “by providing the use of prison facilities, transportation, and general support” for the purposes of deportation hearings.

Some lawmakers, including state Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara), expressed frustration over the different interpretations of the state’s responsibility to ICE.

“I recall it being fairly clear in hearings that we’ve had over the course of the last several years that the state of California does not see itself as an extension of ICE,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.