L.A. is facing the most dangerous moment of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here’s how we got here

Los Angeles County is facing its most dire moment since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

The coronavirus is spreading at unprecedented rates. The number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 has shot up by 78% over the past month. There is a risk a new stay-at-home order may be coming.

And perhaps most troubling, no one is sure how much worse it will get.

Much depends on how people spend Thanksgiving. With so many people infected, traditional holiday gatherings could turn into super-spreader events, in which a large number of people are infected, making an already critical situation much worse. Public health leaders have been trying to drill down the point that the dangers are everywhere, especially from highly contagious family and friends who seem perfectly healthy.

“It is safe to assume that many people are infected without even knowing it yet,” Dr. Muntu Davis, the L.A. County health officer, said this week.

But officials also stress we still have time to improve conditions. After all, L.A. County has rallied before to curb the spread of COVID-19 — twice, in the spring and then the summer.

“This has been a community that has rallied before and done the right thing,” said Barbara Ferrer, the county’s public health director. “And if there ever was a time to get back to doing the right thing, it’s right now.”

There are some advantages to what’s happening now compared with the first weeks of the pandemic — mortality rates among those who are hospitalized with COVID-19 are down as a result in improvements doctors have learned in treating patients.

But if coronavirus infections continue to spread and hospitalization rates become worse than the summertime record, “more people will die,” Ferrer said.

“If we start exceeding the level of surge on cases that we saw in July, we will have a big problem in hospitals,” Ferrer said.

And in just the past several days, there has been an increase in daily COVID-19 deaths in L.A. County. For the seven-day period that ended Friday, an average of 22 COVID-19 deaths have been reported daily, a number that hasn’t been seen since Oct. 1.

That’s an 86% increase in average daily deaths in just eight days.

“The hope is that we do every single thing we can starting right now. We’re a little behind, to be honest,” she said.

Ferrer pointed out that officials have been warning about the increase in cases for three weeks now, and she’s hopeful that people have already taken heed of the warnings, and that a reduction in new daily cases will come soon.

But a portion of today’s coronavirus cases — 12% — are expected to end up in the hospital in two to three weeks, and a certain fraction of them will result in deaths.

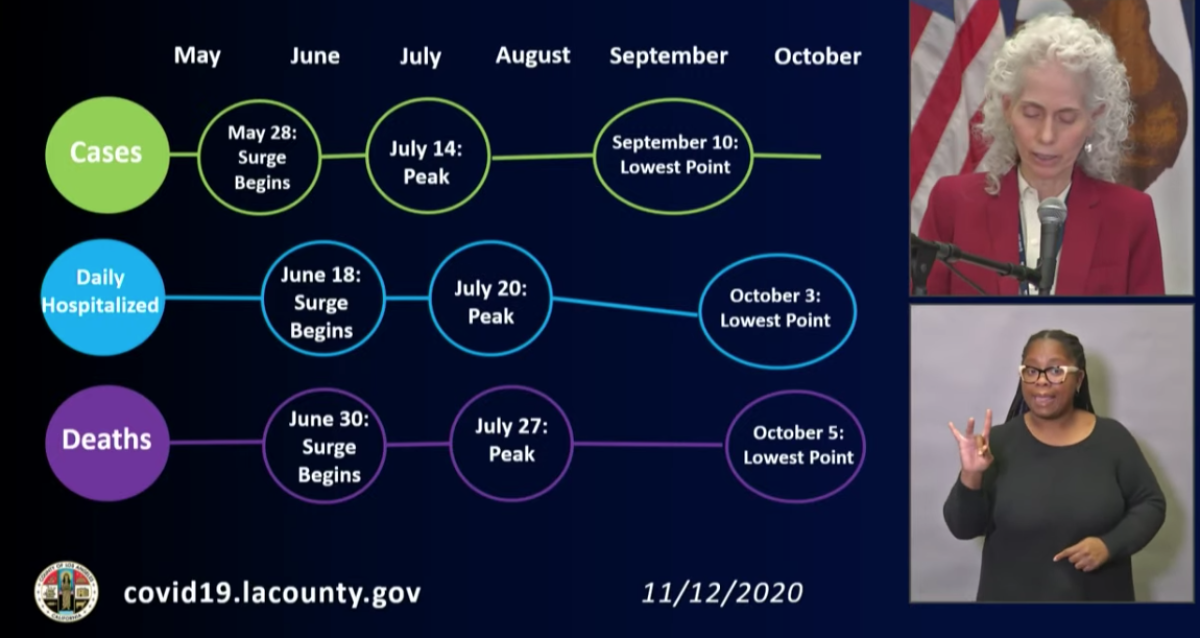

The last surge in L.A. County lasted four months.

The surge in coronavirus cases started shortly after Memorial Day, but because of the many weeks it takes for people to become seriously ill with the virus and subsequently die, the peak in deaths in the summer occurred two months later, at the end of July.

It was only at the beginning of October that daily deaths hit a low point in that wave of disease.

Here are five reasons why California faces its most dangerous moment yet in this pandemic.

Daily cases are heading to unprecedented levels

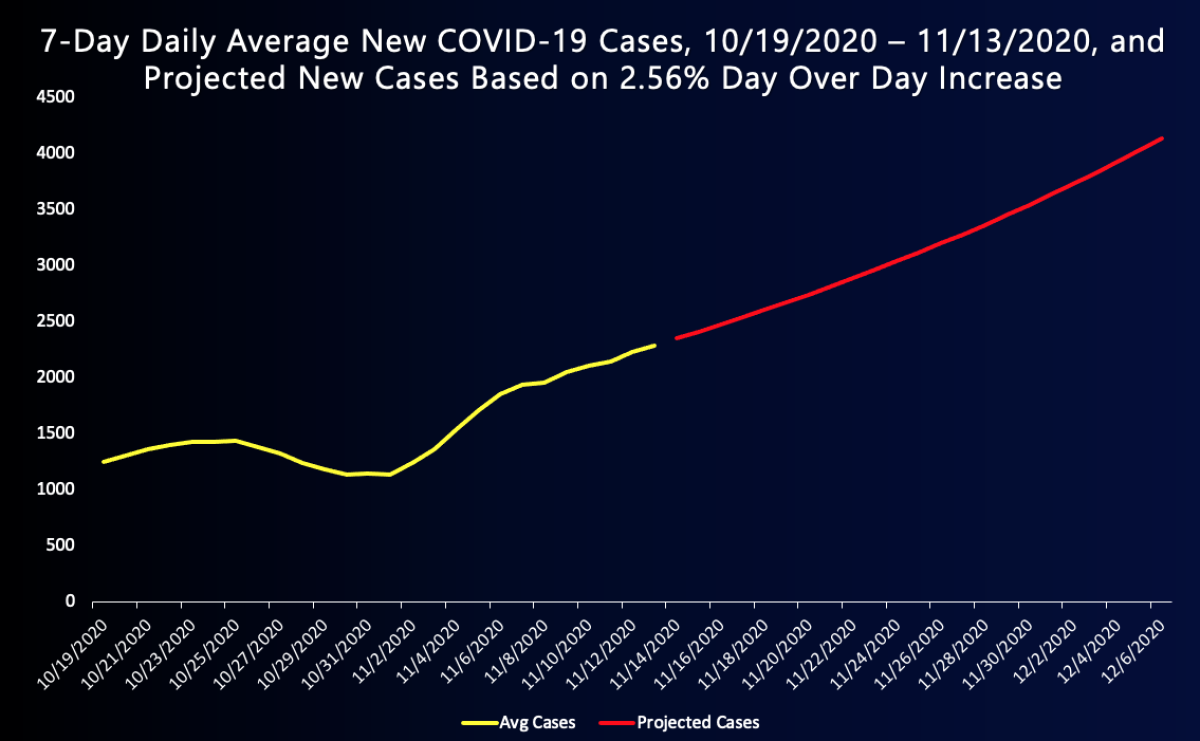

Daily cases have been climbing in L.A. County since late October, and accelerated acutely in the last several days.

A Times analysis found that L.A. County is reporting an average of 3,613 coronavirus cases a day over the previous five days as of Friday. If that rate hits 4,000 cases a day — a scenario that could plausibly happen in a matter of days — county officials say they’ll order an end to outdoor restaurant dining and require eateries to serve food only by delivery or takeout.

And if that rate hits 4,500 a day, authorities warn they’ll order a stay-at-home order, which would allow only essential and emergency workers and those securing essential services to leave their homes, and impose a 10 p.m.-to-6 a.m. curfew that would generally only exempt essential workers.

Officials say they’ll give a three-day notice before a new health order is made effective.

Earlier this week, Ferrer said the county was on pace to see an average of 4,000 coronavirus cases a day by early December. But an even worse acceleration of daily cases in recent days may mean that threshold might be achieved much sooner than anticipated.

Hospitalizations have climbed in L.A. County for the past six weeks

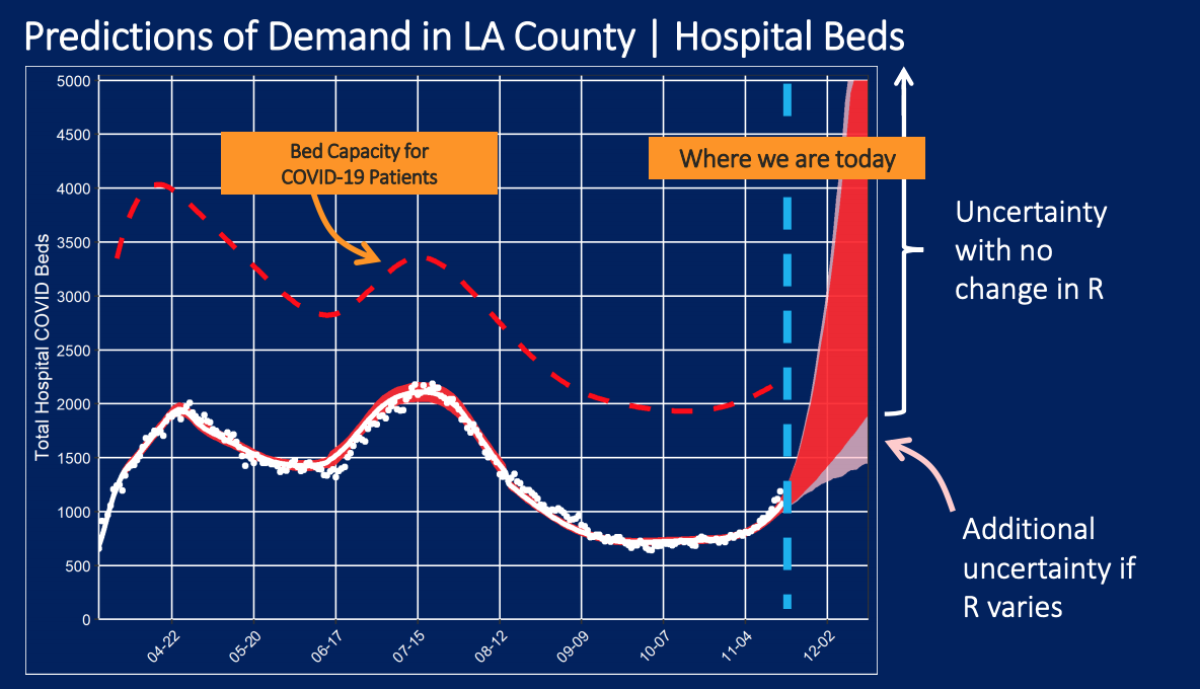

COVID-19 hospitalizations have been climbing in L.A. County for the past six weeks, and the pace of the increase has quickened in the last 2½ weeks.

The number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 countywide has shot up by more than 75% over the past month — from 730 on Oct. 18 to 1,298 as of Wednesday.

If COVID-19 hospitalizations pass the threshold of 1,750 in L.A. County, officials say they plan to order restaurants to close outdoor dining areas. And authorities plan to issue a new stay-at-home order if hospitalizations pass 2,000.

Ferrer said it’s possible that the number of people hospitalized with coronavirus infections could be between 1,600 to 2,600 by early December.

Latino residents are being hit harder by COVID-19, again

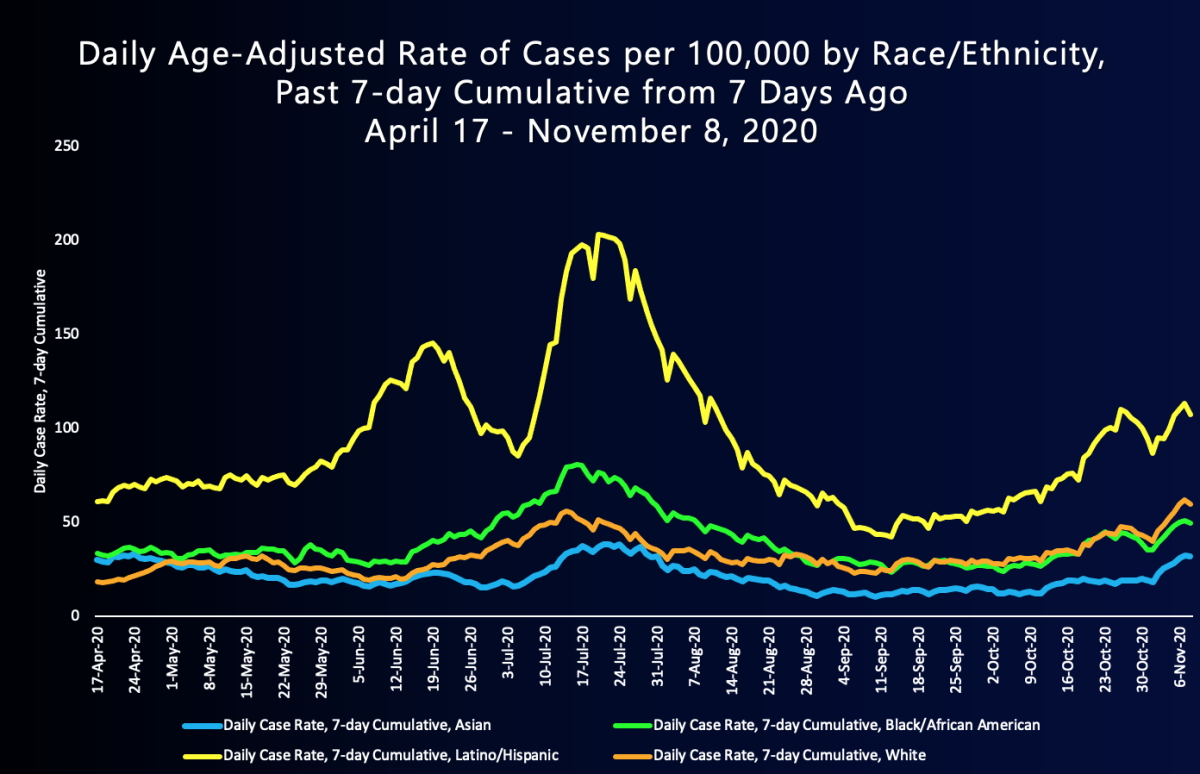

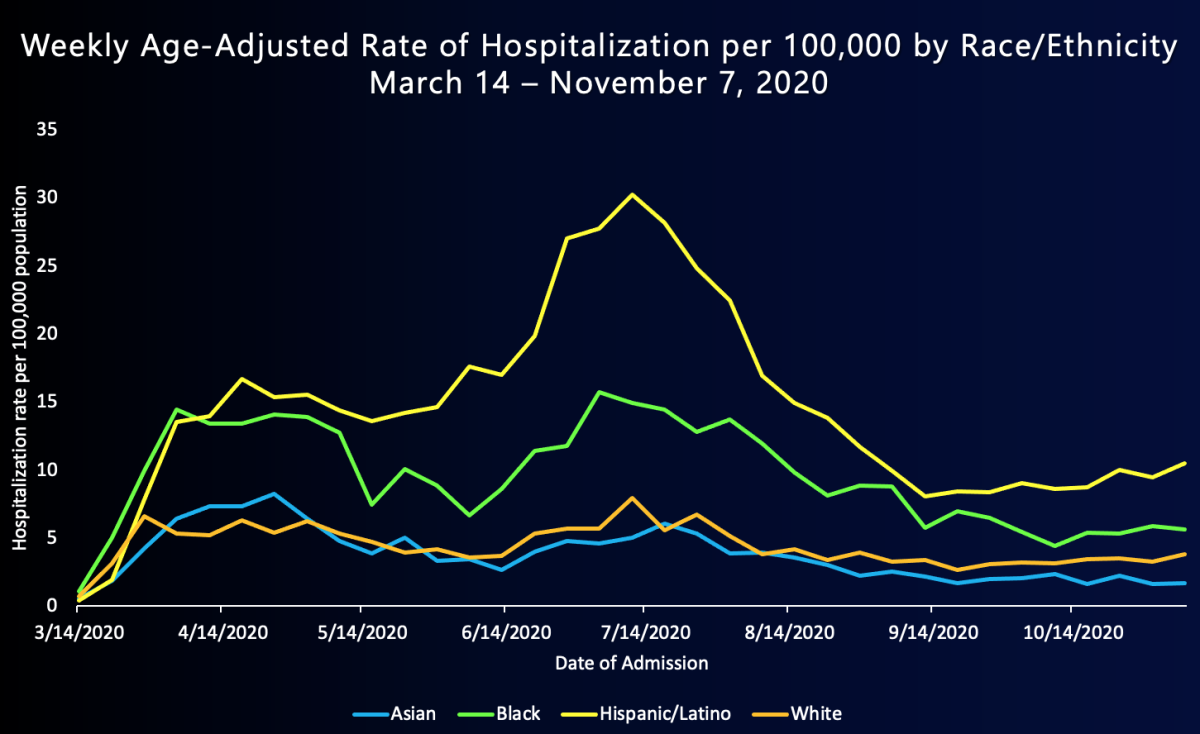

Latinos — California’s largest ethnic group — are being hit harder by the pandemic yet again in Los Angeles County.

In mid-July, Latino residents suffered four times the daily age-adjusted rate of coronavirus cases of white residents, a disparity that shrank to less than twice that of white residents by mid-September. But in recent weeks, the disparity has grown again, Ferrer said.

Latino residents are also experiencing increasingly disproportionate rates of being hospitalized with COVID-19 in L.A. County. In mid-July, Latino residents had an age-adjusted hospitalization rate triple that of white residents, a gap that narrowed later that summer.

“Unfortunately ... the gap is growing once more,” Ferrer said.

Latino residents are also disproportionately dying at higher rates from COVID-19 than white residents, and there is a fear that the gap will widen in the coming weeks if the overall death rate does rise, Ferrer said.

The disparities are also being seen elsewhere.

In Santa Clara County, where Silicon Valley is located, coronavirus case rates among Latino and Black residents are increasing more sharply than among white residents, said Dr. Sara Cody, the Santa Clara County health officer.

“When our rates are low, those disparities decrease. And as the rates increase, so do the disparities,” Cody said.

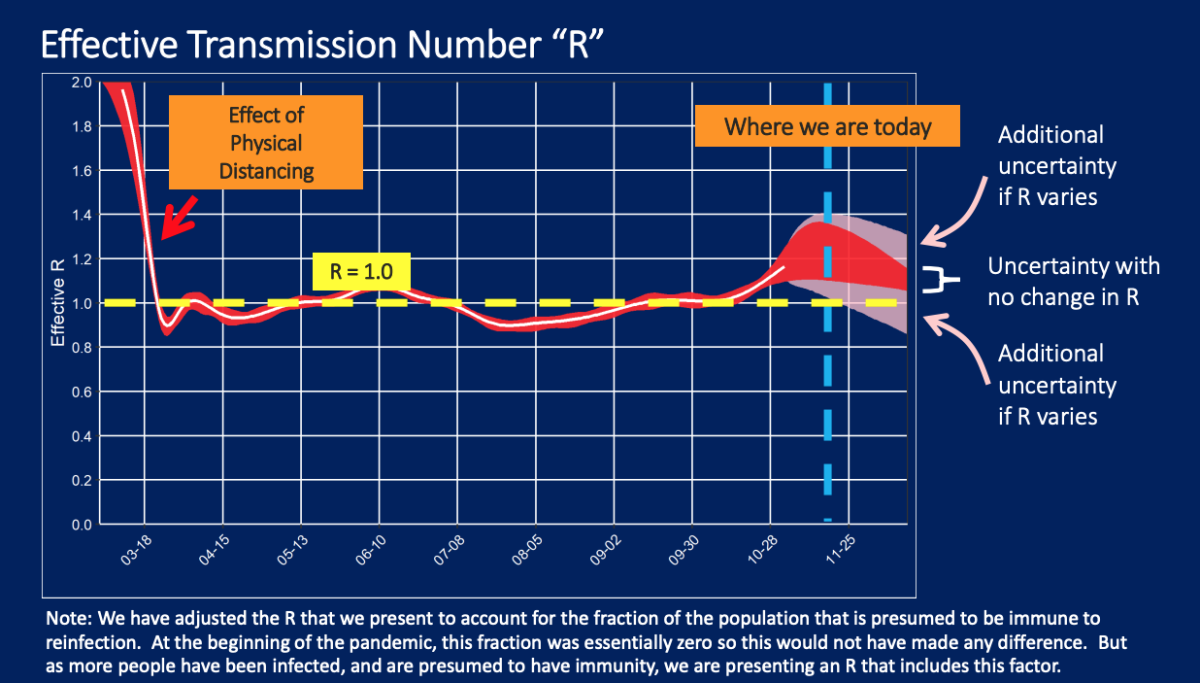

The transmission rate of the virus is at its worst level in months

The effective transmission rate of the coronavirus in L.A. County is now estimated at 1.18, meaning that every person infected with the virus on average transmits it to 1.18 people.

“This is a marked increase from last week, when we estimated that the [transmission rate] was 1.03,” said Dr. Christina Ghaly, the L.A. County director of health services.

The latest number is close to reaching the previous summertime high of 1.26, recorded in late June.

The current increase in hospitalizations in L.A. County is being caused by accelerated transmission of the disease three weeks ago, Ghaly said.

San Francisco’s virus transmission rate is even worse. “It’s at 1.3,” Mayor London Breed said on Tuesday, up from a rate of 1.2 last week.

The supply of hospital beds is once again at risk

Until this week, there had only been a gradual increase in COVID-19 hospitalizations in L.A. County, Ghaly said.

“But the data from this week shows a marked difference,” Ghaly said. “We are seeing a significant increase in the number of new patients that must be admitted to the hospital with COVID-19.”

In September, L.A. County recorded about 100 new cases of patients with COVID-19 needing hospital admission every day. “Now, that number is closer to 200,” Ghaly said.

The sharp increase in hospitalizations is a warning sign.

“It is highly likely that we will experience that highest rates of hospitalizations that we have seen in the COVID-19 pandemic to date within the next month unless we take action immediately to substantially reduce transmission within our communities,” Ghaly said.

“And even if we do take decisive action today — even if everyone does their part — we will continue to see an increase in hospitalizations for at least the next two to three weeks, as it typically takes that long for those who have been exposed to become ill and require hospital-level care,” Ghaly added.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.