Business is booming for Maria Mir. Under normal circumstances, she takes little time off in November and December; the holidays are her busy season. But this is 2020. Nothing is normal. And everyone seems to need her at once.

Mir is a licensed marriage and family therapist. She’s used to patients feeling lonely and depressed as Thanksgiving and Christmas near. But “this particular time is different,” she says. “Even people who haven’t felt lonely in the past are now feeling that isolation.”

Pandemic Holiday Season 1.0 is taking its toll on psyches and pocketbooks. We’ve been cooped up for the better part of nine months, but instead of drawing up lists of guests and gifts, we’re cataloging the things we cannot do as temperatures drop and coronavirus cases soar across the country.

Like visit far-flung family and friends. On Friday, the governors of the three West Coast states issued “travel advisories” recommending against nonessential travel and urging people entering California, Oregon and Washington to self-quarantine for two weeks to slow the virus’ spread.

Or buy those loved ones holiday gifts. A second round of stimulus money to help hard-hit consumers is a distant dream because of a deadlocked Congress. And even if shoppers have money in their pockets, malls are what health experts warn against: closed-in spaces with the possibility of crowds.

Or even, for the high school seniors among us, apply for college in any normal fashion. Campuses are largely on lockdown. Learning is remote. The extracurricular activities that burnish an application are on hold. And you can’t bump into your counselor in the hall for a little extra guidance.

One of Mir’s patients is so distressed about being unable to see her extended family that she doesn’t plan on celebrating Thanksgiving at all. She hasn’t seen out-of-town relatives since last Christmas. She doesn’t know when she’ll see them again.

“The client is hoping somehow to have the power to order food or cook a small Thanksgiving dinner,” said Mir, a lifelong Southern Californian who now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and has practiced remotely since her daughter was born four years ago. “But emotionally, she’s decided it’s just too hard to celebrate the holiday … too hard to be away from family.”

Even Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer is feeling the sting of the first coronavirus Christmas season. Her grandchildren live in another state, and she won’t be able to see them for the holidays.

“Like all of you, I wish things were really different. But they’re not,” she said at a media briefing Thursday. “And my feeling is, I don’t want to be one of the people that’s contributing to not only increasing cases that restrict our ability to continue with our recovery journey, but increasing cases that could result in other people getting sick and even dying.”

For months now, Sharnell Blevins has had a full house. Because of the coronavirus, Blevins and her husband work from their South Bay home —along with their six children. Three are college undergrads still home because of the pandemic. One is a freshman at an East Coast university and wakes up at 5 a.m. for class. The other three are in high school.

“Sharing the internet can get tricky,” Blevins said. “We sometimes have trouble with connectivity, but space is the biggest issue. We’ve all claimed different corners of the house.”

Her fraternal twins are in 12th grade in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Her daughter has been playing basketball since she was 4 and has been on the varsity team all through high school. The California Interscholastic Federation, which governs student sports, planned to have the season start in January. But coronavirus cases are on the rise, and basketball is on hold.

“We always knew that the rates would probably spike in the fall,” said Blevins, “but the latest news certainly puts a damper on everything. I was hoping that January would be when my kids would be able to go back to school, that we’d all get our lives back. It’s scary. We could still be like this next year.”

On a typical Thanksgiving, said Blevins, there are as many as 20 people in her home. This year, she still has not made plans. At most, the immediate family will probably share a meal — without her and her husband’s elderly parents, whom they fear putting in coronavirus danger.

“You know, I thought about having a Zoom dinner to include them, but that feels a little weird,” Blevins said. “It’s just not very intimate.”

Downtown Santa Monica was a subdued shadow of its usual self Friday, 24 hours or so after California hit a terrible milestone: more than 1 million people in the Golden State have been confirmed to be infected with COVID-19.

Longtime friends Regina Mitchell, Lakisha Johnson and Angela Robertson-Jones took a girls trip south from the Bay Area, hoping to beat store closures they expected to encounter with the pandemic’s third wave. Johnson was planning to get a coat at the Zara on 3rd Street, but she and her friends said they wouldn’t be doing any holiday shopping there — or anywhere — the way they’d done in previous years.

“I’m ordering a lot online. And I’m only ordering essential gifts — a cute flashlight, maybe even gift cards to the grocery store,” Mitchell said.

Robertson-Jones agreed. “My son is 2, he doesn’t need anything,” she said. “Last year was definitely different. But right now, money is for essential things.”

Patricia Santiago lost her food service job when the pandemic hit in the spring, and since then, work in her former industry has been scarce. Retail bounced back faster, and these days she works as a clerk at a discount clothing store on Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade.

But she makes just $13.50 an hour. And it costs her $20 a day to park near her new job. The alternative — two hours each way on the bus — feels more dangerous now than it did when she started four months ago.

The future feels just as precarious. In October, her boss began cutting hours in response to disappointing sales. The anemic start to what is normally the busiest shopping season of the year has her worried.

“A lot of us ended up without jobs” because of the virus, she said. “We have to look for another way to provide for our families.”

But she also understands why shoppers are staying home.

“We have to pay rent and the car — if we don’t need it, we don’t buy it,” Santiago said. “Not this year.”

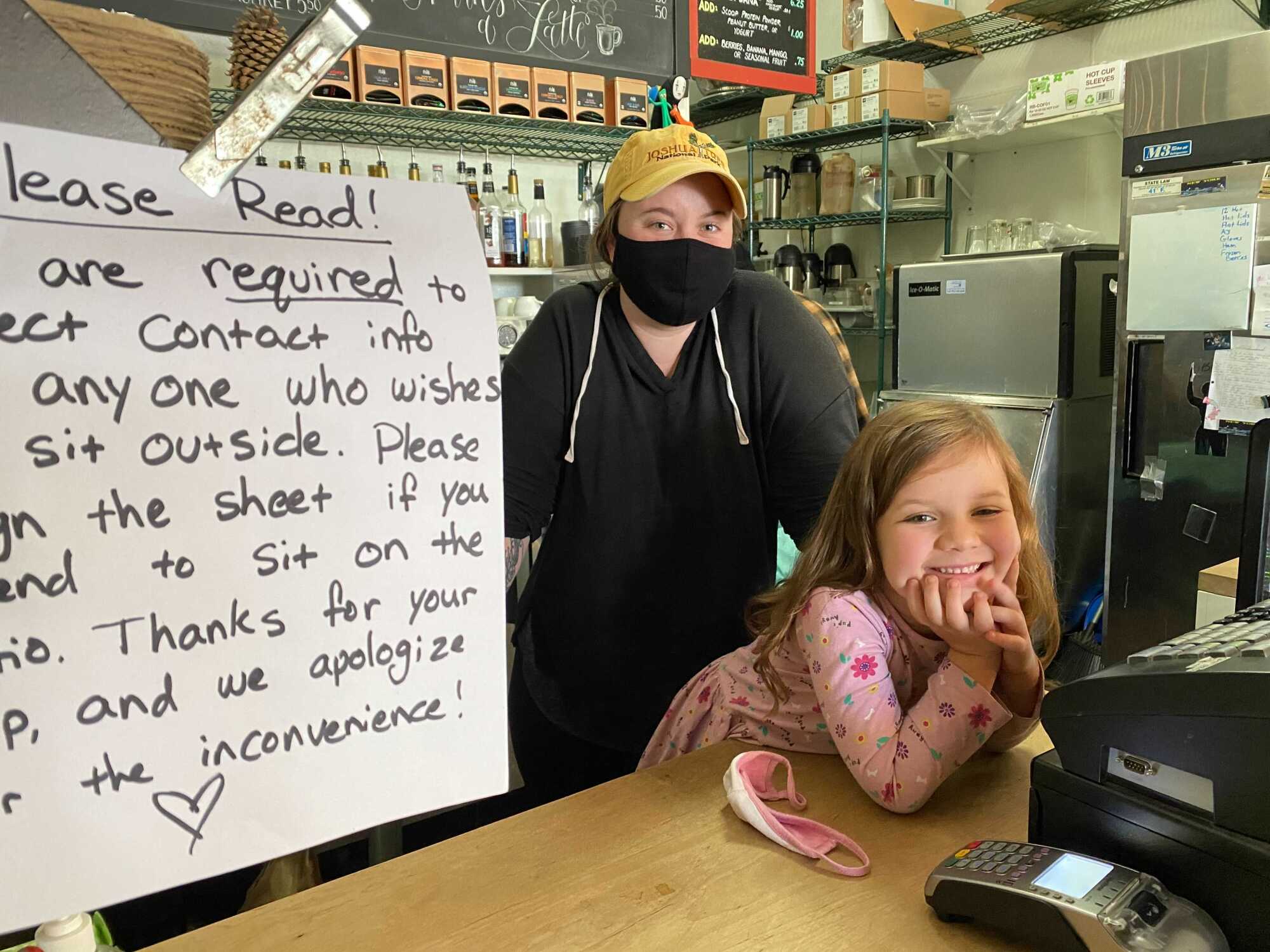

Twenty or so miles south, business is down at the coffee shop Jenny Maddox owns with her sister. On Friday afternoon, she was pulling shots and greeting regulars at Old Torrance Coffee & Tea and wondering whether her Thanksgiving plans would fall apart.

The year 2020 hasn’t been all bad for the 29-year-old Gardena woman. In January, she got married in the coffee house where she’d worked since college. Now she, husband J Lee Maddox and her 5-year-old daughter, Kennedy Anne Coen, were hoping to fly to Indiana to spend Thanksgiving with her in-laws.

“But Indiana is having a spike” in virus cases, she said. “We’d have to fly into O’Hare, and Illinois has travel restrictions. Indiana doesn’t as of yesterday, but who knows.”

And now, California does. As a small-business owner, she said, she can’t afford to quarantine for two weeks on her return. But she wasn’t all that worried by the new regulations: “Nothing’s ever for sure,” she said. “People just like to pretend it is. And now they can’t.”

And Kennedy was downright giddy at Gov. Gavin Newsom’s announcement that “travel increases the risk of spreading COVID-19, and we must all collectively increase our efforts at this time to keep the virus at bay and save lives.”

She loves the color pink. And unicorns. And the governor of California.

Given the recent backlash against Newsom’s efforts to stanch the virus, the protests, the recall petitions, Kennedy might be part of a very small fan club.

“Gavin Newsom gave new advice for traveling,” Maddox told her daughter, who was building something or other with a set of wooden chess pieces. “That means he’ll probably have a picture in the newspaper.”

Kennedy collects pictures of Newsom and pastes them into a pink scrapbook she put together in honor of the politician. On the first page, she drew a picture of the governor with his name above his head in brown marker.

In pencil at the top of the page she wrote: “I love my favorite person.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.