REDDING — The influence of Bethel Church can be felt all over this economically stressed Northern California city.

In the Redding police officers whose positions the megachurch funded. The once-dying civic auditorium it keeps afloat. The church elder on the Redding City Council.

Bethel can be felt in the trendy new coffee shops and restaurants where young, well-dressed people huddle at tables with open Bibles and nary a mask in sight. It can be felt in parking lots and on sidewalks where believers approach strangers, asking to pray for and heal them.

In downtown Redding on a recent afternoon, Chevon Gilzene, a 25-year-old student at the church’s Bethel School of Supernatural Ministry, declared: “We want to love the city well.”

It is a proclamation that is as disputed as it is acclaimed across Redding, a city of 92,000 where more than 10% of the population attends the nondenominational Christian megachurch.

But anger toward Bethel Church intensified after members and students fueled such a major spike in coronavirus cases that Shasta County briefly fell backward to the most restrictive tier on California’s reopening plan.

In recent weeks, more than 300 COVID-19 cases have been reported by the church and its Bethel School of Supernatural Ministry (or BSSM), an unaccredited school focused on prophecy and miracles. It has been the largest cluster of cases in Shasta County.

The outbreak — which local officials blame on crowded living conditions for students and leadership publicly questioning the effectiveness of masks — has since been brought under control, with fewer than a dozen active cases. But its effects linger.

“The perception from that is they don’t really care,” Shasta County Supervisor Leonard Moty said. “What we tried to tell them is, if you really want to be part of the community, you have to do more to respect the community.”

The church sits at a nexus of faith, politics and celebrity. It has provoked a debate not just on the influence of its famed pastors and high-profile members — who have written books, produced worship albums and have massive social media followings — but on how much it is channeling another leader 2,800 miles away: President Trump.

Some religious experts say Bethel’s actions are indicative of a growing wave in American religion that eschews teachings of traditional denominations and embraces fame and prosperity — and charismatic leaders — in tune with the conservatism of Trump. It has been especially successful in drawing in young worshipers.

“That would be true of Donald Trump as well; he has somehow woven magic with these people, and they think he can give them something they want,” said Richard Flory, senior director of research and evaluation at the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

The church’s worship music label Bethel Music brought in $12 million in revenue in 2017, and its Bethel Media raked in more than $4 million, according to tax returns. Bethel also started Jesus Culture, a revivalist youth ministry with its own record label that hosts conferences around the world.

“They make millions and millions and millions of dollars off the back of their congregation and their music,” said Joshua Barbour, a former megachurch worship leader, based in Canada, who now hosts a podcast about the inner workings of large churches.

Bethel’s pastors have embraced Trump. Senior leader Bill Johnson endorsed him in an op-ed in The Christian Post, and senior associate leader and BSSM co-founder Kris Vallotton claimed to prophesy last year that God wanted him reelected.

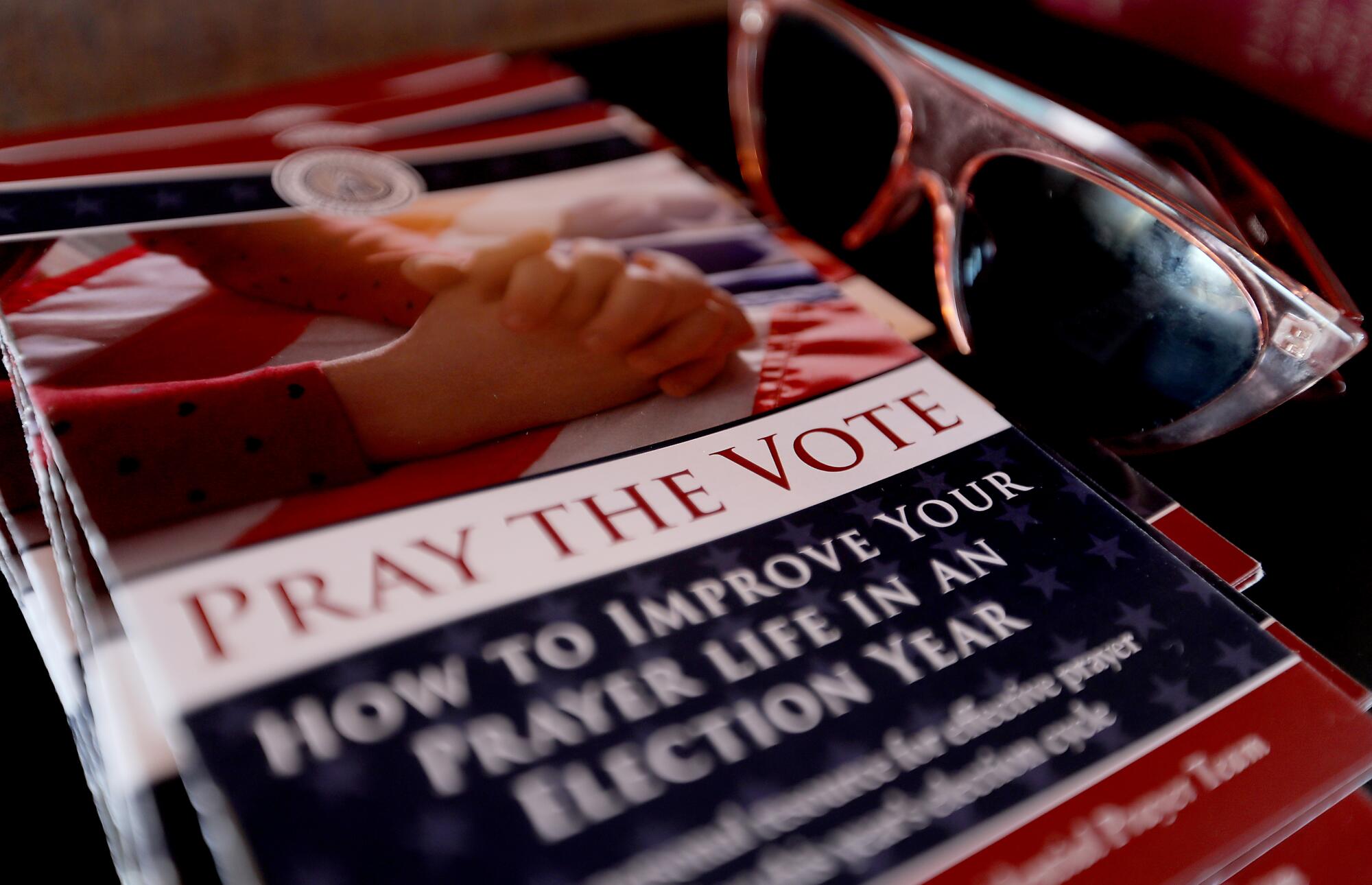

In an email, Bethel spokesman Aaron Tesauro said the church “does not promote or endorse any political candidates [and] have always believed that part of the Christian faith includes praying for those in leadership positions.” It has, however, openly opposed California bills seeking to crack down on LGBTQ “conversion therapy,” which claims to “heal” people of homosexuality, and encouraged members to contact legislators.

Some former Bethel members say the church has grown more blatantly political in the era of Trump, who has appealed to the Christian right by vowing to repeal the Johnson Amendment, a 1954 law that bars tax-exempt organizations from engaging in political activity.

Amid the Bethel coronavirus outbreak, Valloton officiated an outdoor wedding for his grandson — with more than 100 guests and few masks — in the tiny Shasta County community of Shingletown. Facing a swift backlash, he posted a video in which he cited Trump’s continuing “having outdoor campaigns where he draws thousands of people.”

“I am willing to sacrifice for my job, my students, my co-workers, my city ... But I’m not willing to, like, give up my life,” he said. “I’m not willing to stop living because there’s a pandemic.”

Johnson’s wife, Beni, a Bethel senior leader, said in a now-deleted Instagram video that masks were “people’s security blankets” and that she refused to shop in a coastal town where she was asked to wear “a stupid freaking mask that doesn’t work.”

Tesauro told The Times that Bethel has strictly enforced health measures, including halting indoor church services and requiring masks, social distancing and COVID-19 tests from all BSSM students and staff before classes started.

But it has been difficult, and confusing, he said, to publicly separate Bethel and its nearly 800 employees from the public messages of a few prominent personalities, each with their own social media followings. Individuals do not always speak for the broader institution, he said.

Among Bethel’s most high-profile attendees is singer Sean Feucht, a volunteer worship leader at the church and failed Republican congressional candidate who led a nationwide “Let Us Worship” tour in defiance of health mandates, drawing thousands of people to Christian music concerts, including at the National Mall.

Bethel Church formally distanced itself from Feucht’s shows after he hosted a crowded gathering at Redding’s Sundial Bridge this summer, saying the church did not sponsor or pay for them. But to the public, the distinction was muddled. Beni Johnson touted his tour on Instagram. And Feucht, in an Instagram caption, called Bill Johnson “a champion to us on this journey.”

Some “Let Us Worship” posts have been censored by Facebook as possibly linked to the baseless QAnon conspiracy theory that alleges Trump is battling a syndicate of Satan-worshiping pedophiles who control the federal government.

Feucht, who has said the allegation is false, did not respond to a request for comment.

Founded as an Assemblies of God church in 1952, Bethel split with the denomination in 2006. It now occupies a hilltop campus at the end of driveway lined by dozens of international flags representing the home countries of BSSM students. The school is credited with singlehandedly increasing diversity in Redding, where 78% of the population is white.

In church services, attendees have reported supernatural “glory clouds,” in which feathers and gold dust fell from the ceiling. Last year, parishioners tried to resurrect Olive Heiligenthal, the 2-year-old daughter of a Bethel worship leader, after she died in her sleep. Thousands of Instagram posts were shared with #WakeUpOlive.

“It’s crazy to me because this doesn’t even feel like my city or my town that I grew up in,” said Donna Zibull, who has lived in Redding for five decades.

Zibull’s grandson, Orian LeBlanc, died in 2014 after collapsing on the street in front of a Bethel member’s home. LeBlanc, who had asthma and an undiagnosed heart condition, was pronounced brain dead at a hospital.

But for four days, Zibull said, the church members came, uninvited, into his room in the intensive care unit. They spoke in tongues, and one member said he could see God in the room. Zibull and her daughter eventually asked hospital staff to remove them.

On a recent Sunday, 20-year-old Ashley Morse, a third-year BSSM student, sat alone in the church’s Alabaster Prayer House, working on a laptop. Growing up in San Diego, her family listened to Bethel Music, and her mother eventually began listening to online sermons. Morse’s older sister enrolled in the school, followed by Morse. This year, her parents are first-year students.

“Coming here has really, really, really helped me cultivate that relationship with Jesus that I didn’t really have before,” she said. “I just grew so much ... and knowing what his voice sounds like, knowing how he speaks to me. Before, I kind of viewed him as kind of like an upset dad.”

Gilzene, the Bethel School of Supernatural Ministry student, wore a mask as she helped shoot a video of a dancer with fellow BSSM pupils. The Toronto native — accustomed to more strict COVID rules in Canada — had planned to get her master’s degree in music but stumbled upon the school after listening to Bethel Music and attending worship conferences.

Gilzene lives with six other young women and contracted a mild case of COVID-19 in September. Gilzene and her roommates, she said, self-isolated immediately. While it’s difficult to control what people do in their personal lives, school leadership has consistently told students to take safety precautions on campus out of concern for the broader city, she said.

“People can’t come into the building and see that,” she said. “Speculation naturally happens. It breaks my heart that it does, but I completely understand and empathize with it.”

Annelise Pierce, a former BSSM student, and her family moved to Redding a decade ago from Uganda, where they did educational aid work with a Christian organization. They had planned to return to the U.S. for a year or so for the sake of their young children, as Ebola began spreading in their town and rebel action grew more concerning. Some friends recommended Bethel.

As a student, Pierce was disturbed by the feeling that you could not question pastors. Vallaton, she said, seemed to be “making it up on the fly,” claiming, for example, that he woke up in the middle of the night craving a milkshake and that that was a message from God.

Among members, “we met a lot of doctors and professors and really high-quality, thoughtful, intelligent people. But also a ton of really young people searching desperately.”

Her family left the church as it grew more political, and she has since abandoned the Christian faith. At a Redding Starbucks, she spoke quietly in a mask, looking around because, she said, members are everywhere.

Doni Chamberlain, an independent journalist, writes regularly about the church. The 64-year-old lost her mother to suicide as a child. She and her sisters were taken in by foster parents who attended Bethel, which was then still an Assemblies of God church.

Church members, she said, told her her mother was in hell. When she and her twin sister were 12, church elders laid their hands upon them trying to cast out demons because they had a form of dystonia, a disorder that causes spasms and convulsions. Their medication was taken away, and they were told that if they believed in God, they would stop having spasms.

Chamberlain, who left the church 42 years ago, said it’s not hard for to spot church members about town. She plays a game she calls Bethel Bingo.

“If you’re in a parking lot and see a crowd of young people, well-dressed, praying around a homeless guy, you go: Bethel!” she said. “God help someone with a crutch because they will converge upon you.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.