How and when the twin domes at San Onofre nuclear plant will come down

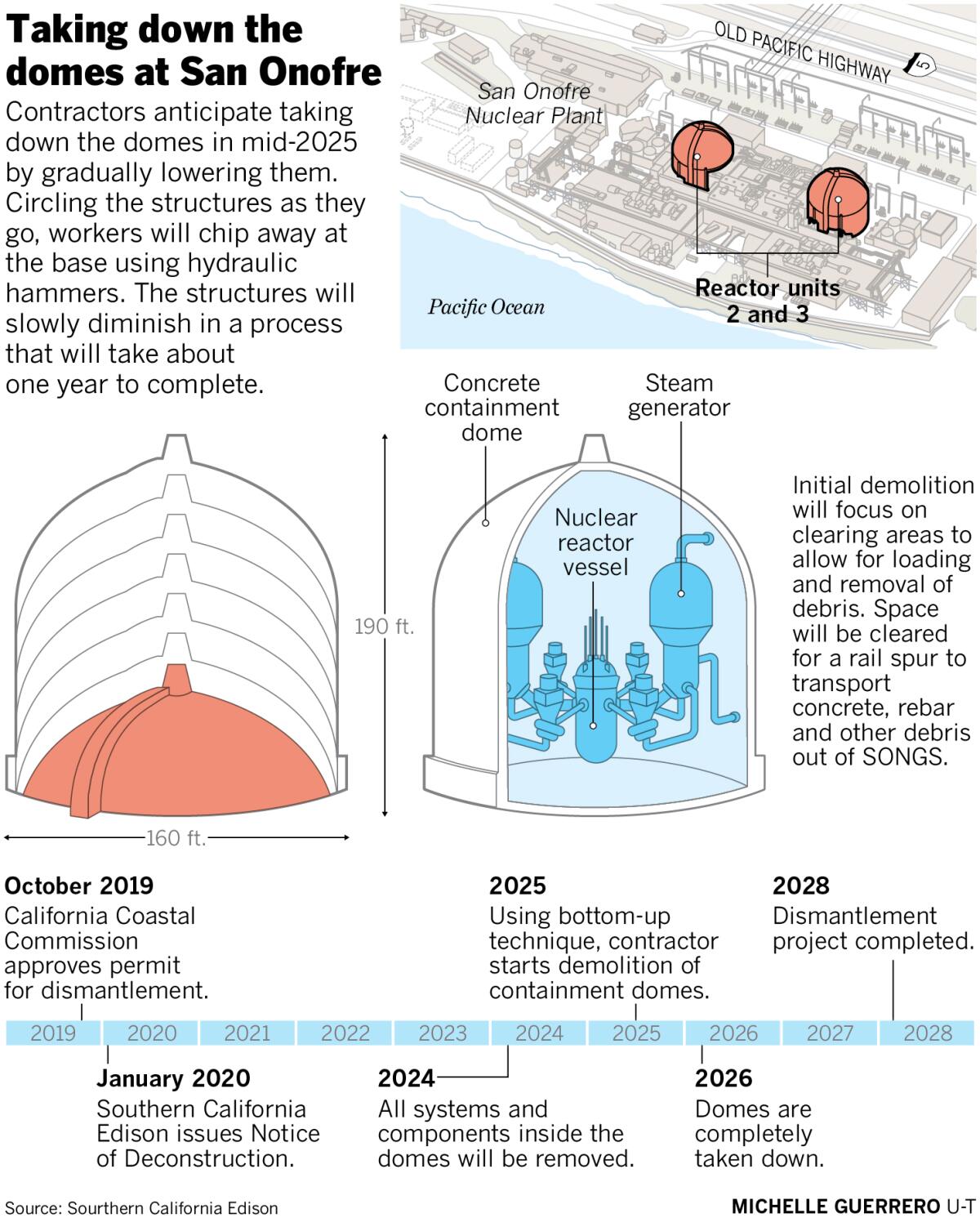

SAN DIEGO — They are perhaps the most distinctive features of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station: the pair of containment domes from Units 2 and 3, rising nearly 200 feet above the ground on the northern edge of San Diego County. Every motorist sees them on the drive along the 5 Freeway.

But in about six years, the twin domes will be gone — obliterated — provided the schedule holds true for dismantling the now-shuttered plant, known as SONGS.

Taking down the domes is part of a much larger project that will remove all but just a few structures at the plant, which produced electricity from 1968 to late 2012 and is being decommissioned by the federal government’s Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Southern California Edison operates the facility, but the massive job of taking the plant apart — and removing the heavy equipment inside it — is being done by a general contractor named SONGS Decommissioning Solutions. The group is a joint venture of the Los Angeles-based infrastructure and engineering company AECOM and Energy Solutions, a Salt Lake City firm that specializes in disposing of nuclear material.

Edison received the needed permit in October 2019 from the California Coastal Commission that cleared the way for dismantlement to begin. Workers have already taken on some jobs, including removing asbestos and establishing staging areas for industrial equipment that can load up and remove debris, such as concrete and rebar. Early work has also begun on the containment domes.

The scale of the overall project is mammoth and complicated. By the time it’s all done, about 2 billion pounds of equipment, components, concrete and steel will be removed from the plant that sits on an 84-acre chunk of land at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton.

What gets taken out of the domes

“The first thing we’ve got to do is get everything out of what’s inside the domes,” said Vince Bilovsky, Edison’s executive director for SONGS decommissioning. “And there’s a lot of stuff in there, a lot of equipment, and it’s big and heavy.”

Among the components inside Units 2 and 3 are piping, tanks, operation systems and steam generators that have absorbed small amounts of contamination over the years. They must be surgically removed in pieces and shipped out as radioactive waste.

“But the most significant component is the reactor,” Bilovsky said. “That takes the most effort to remove and dispose of those parts.”

To get the heavy equipment into the domes, workers have to enlarge the opening. To do that, they have to take out the “tendons” that had been built within each unit’s four feet of reinforced concrete. The tendons act like cables that horizontally and vertically hug the containment domes.

Work has already started to remove the tendons in Unit 2. By the first quarter of next year, they will be removed from both units.

Once a larger opening into each dome is made, the dismantling equipment can be installed.

Things get interesting when workers tackle the reactor vessel. The reactor is in a cavity and will be cut up into pieces. But because the internal parts of the vessel were close to nuclear fuel, they are classified as low-level radioactive waste and have to be treated as such during dismantlement.

That means the process of cutting and retrieving of the pieces is done underwater.

To do that, each cavity is filled with about 500,000 gallons of treated, demineralized water.

Operated remotely by a crew using underwater cameras, the internal components of the reactor vessel will be pulled out one by one, and then cut into pieces with a rotating saw. Using robotics, the pieces are then retrieved and placed into containers. The operation requires a crew of 12 to 20 people.

It sounds unconventional, to say the least, but Bilovsky said the underwater operation has been used at decommissioned plants such as Zion in Illinois, Connecticut Yankee in the Northeast and the Trojan Nuclear Power Plant in Oregon.

The two reactor vessels are each about 25 feet tall, 16 feet in diameter and weigh more than 1 million pounds.

How the domes will come down

Taking out everything inside the containment domes will take about five or six years. Once the domes are empty, they can then be dismantled.

But don’t get your hopes up for the type of dramatic implosions seen when some high-rise buildings come down.

Instead, the plan at SONGS is to gradually reduce the size of the domes — from the bottom up, until their nearly 200-foot height is reduced to zero. The domes are 160 feet wide.

“There’s no explosives, no wrecking ball, just a slow process,” Bilovsky said.

After an inner liner is removed, hydraulic hammers on the exterior of the dome chip away at the bottom of the structure. It very slowly collapses as workers move around the dome’s circumference.

“It’s a very methodical, slow, controlled process,” Bilovsky said.

The schedule calls for the domes to start shrinking about mid-2025, and roughly one year later, they will be completely gone.

“They’re iconic structures that everybody who has driven between San Diego and Los Angeles knows about,” Bilovsky said.

What will get carted off

The domes may be the most notable structures to get dismantled, but there are plenty of other pieces of the plant that will be shipped away, to be classified as low-level nuclear waste:

- About 285,000 tons (570 million pounds) of material at SONGS will be labeled Class A, the lowest level. It makes up the vast majority of the plant’s remains and will be sent to the Energy Solutions disposal facility in the town of Clive, Utah. Most of the waste will be sent to Utah by rail.

- Some 35 tons of Class B and C low-level waste will get shipped by truck to the Waste Control Specialists facility in the West Texas town of Andrews. Bilovsky estimates the shipments will amount to about six to eight truckloads.

An additional 125 tons of material classified as higher than Class C low-level waste will remain at SONGS. The waste will be put into 12 horizontal canisters — the same types of canisters Edison used to store spent fuel assemblies at the original storage site at the north end of SONGS.

From a policy perspective, the 12 new canisters will be treated the same as SONGS spent fuel and will be eligible to be moved to a permanent or interim repository, when and if the federal government ever opens one.

The costs for dismantling SONGS will come from about $4.5 billion in existing decommissioning trust funds. The money has been collected from ratepayers and invested in dedicated trusts. According to Edison, customers have contributed about one-third of the trust funds and the remaining two-thirds have come from returns on investments made by the company.

Barring any unforeseen events, Bilovsky said, $4.5 billion will be sufficient to cover the project, adding that “we’re fairly confident with the schedule” that all the work will be completed in eight years.

Critics of Edison’s longtime management of the plant are skeptical whether the complex dismantlement plan can be completed on time or without major issues.

“Edison has only committed to doing what is ‘commercially reasonable’ to handle nuclear waste that has been stranded at San Onofre,” said Gary Headrick, co-founder of the environmental group San Clemente Green. “Their current wishful plan might just work, but what if it doesn’t, like so many other past examples you could point to?”

SONGS has not produced electricity since 2012 after a leak in a steam generator tube led to the closing of the plant.

In August 2018, transfers of canisters filled with nuclear waste from “wet storage” pools at the plant to a newly constructed “dry storage” facility were suspended for nearly a year after a 50-ton canister filled with fuel assemblies came to rest on a metal flange, 18 feet from the floor of a storage cavity, for about 45 minutes to an hour.

The canister, left unsupported by the rigging and lifting equipment intended to shoulder its weight, was eventually lowered without falling. The incident led to a special inspection by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which fined Edison $116,000.

Transfers of the spent fuel resumed after Edison instituted a series of improved safety measures, and in August of this year, the 73rd and final canister was lowered into its storage cavity at the north end of SONGS.

What will be left at SONGS?

When the dismantlement project is completed, all that will remain will be the two dry storage sites; a security building with personnel to look over the waste; a seawall 28 feet high, as measured at average low tide at San Onofre State Beach; a walkway connecting two beaches north and south of the plant; and a switchyard with power lines.

The switchyard’s substation without transformers stays put because it houses electricity infrastructure that provides a key interconnection for the power grid in the region.

The canisters of nuclear waste remain between the 5 Freeway and the Pacific Ocean because the federal government has not found a place to put all the used-up commercial fuel that has stacked up at some 121 sites in 35 states.

Some 80,000 metric tons of waste from commercial nuclear plants exists across the country. SONGS accounts for 1,609 metric tons, or about 3.55 million pounds.

Nikolewski writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.