With dry La Niña conditions, persistent Western drought looms large in winter outlook

The forecast looks warm and continued dry this winter in California and the Southwest, which raises the disturbing prospect of a perpetual fire season.

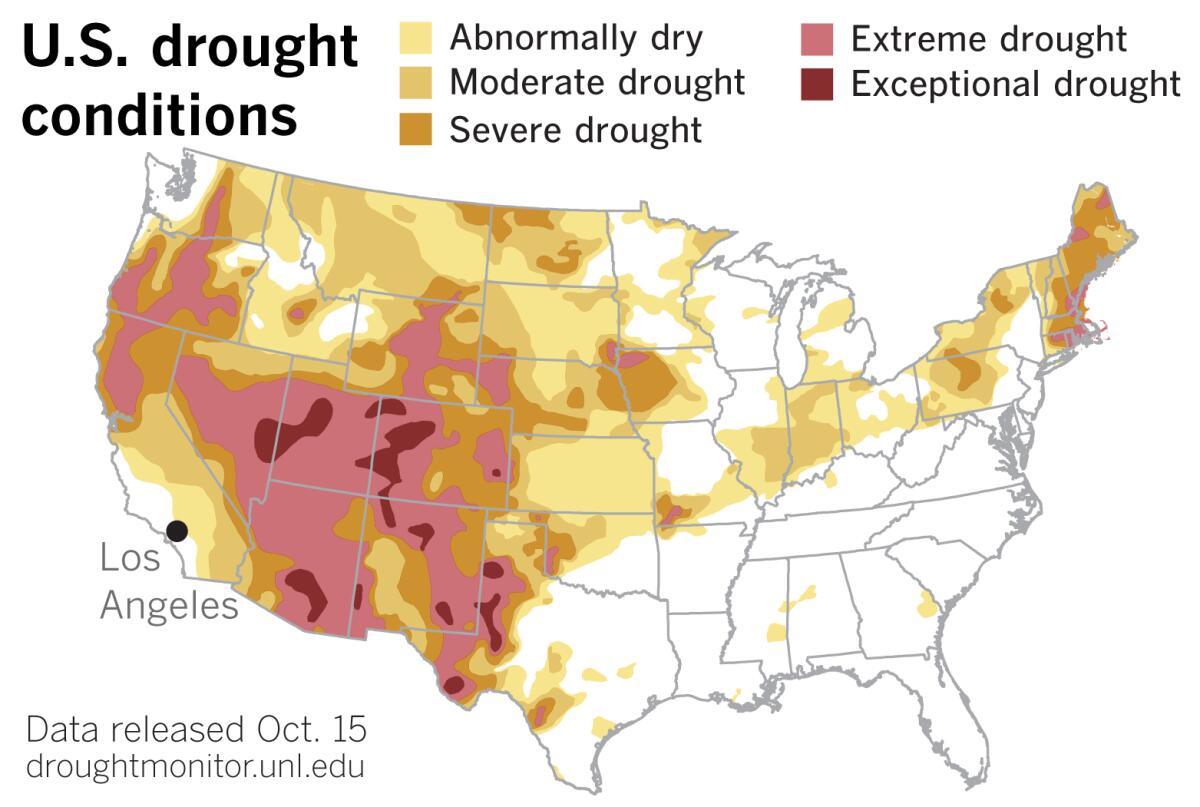

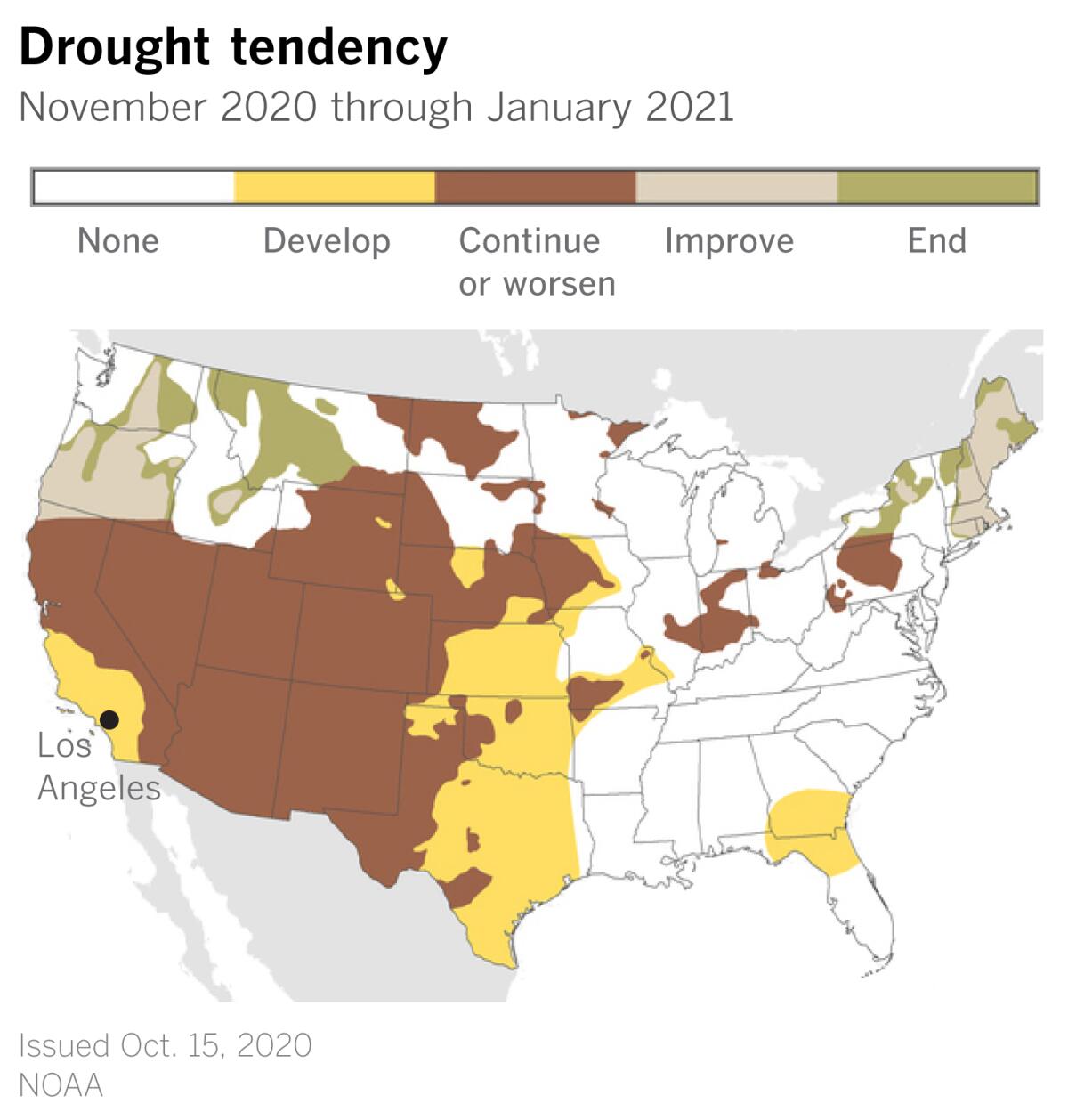

More than 45% of the continental U.S. is experiencing drought right now, especially in the West. With a La Niña climate pattern well established and expected to persist, the drought may expand and intensify in the southern part of the country during the winter ahead, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted.

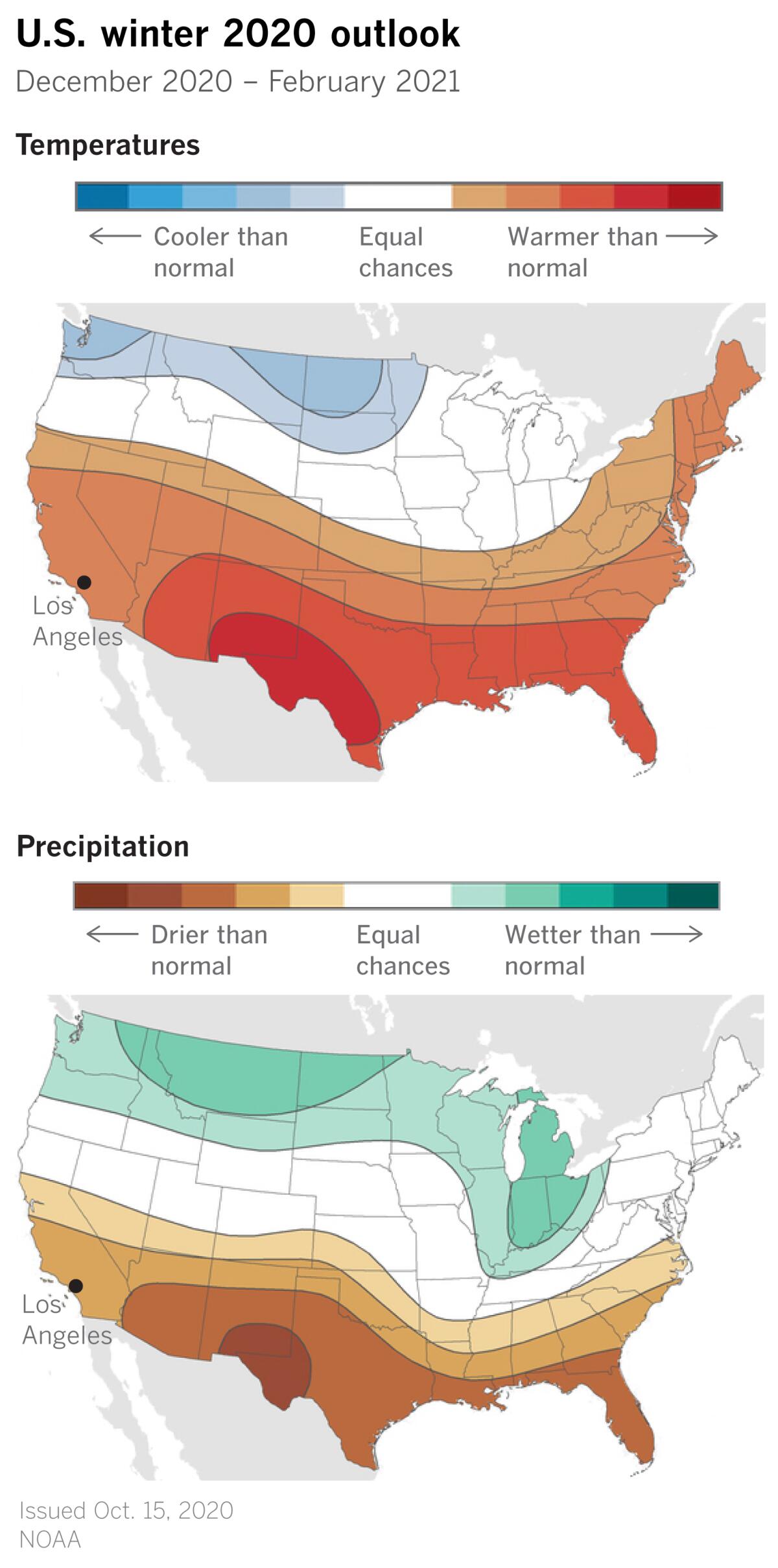

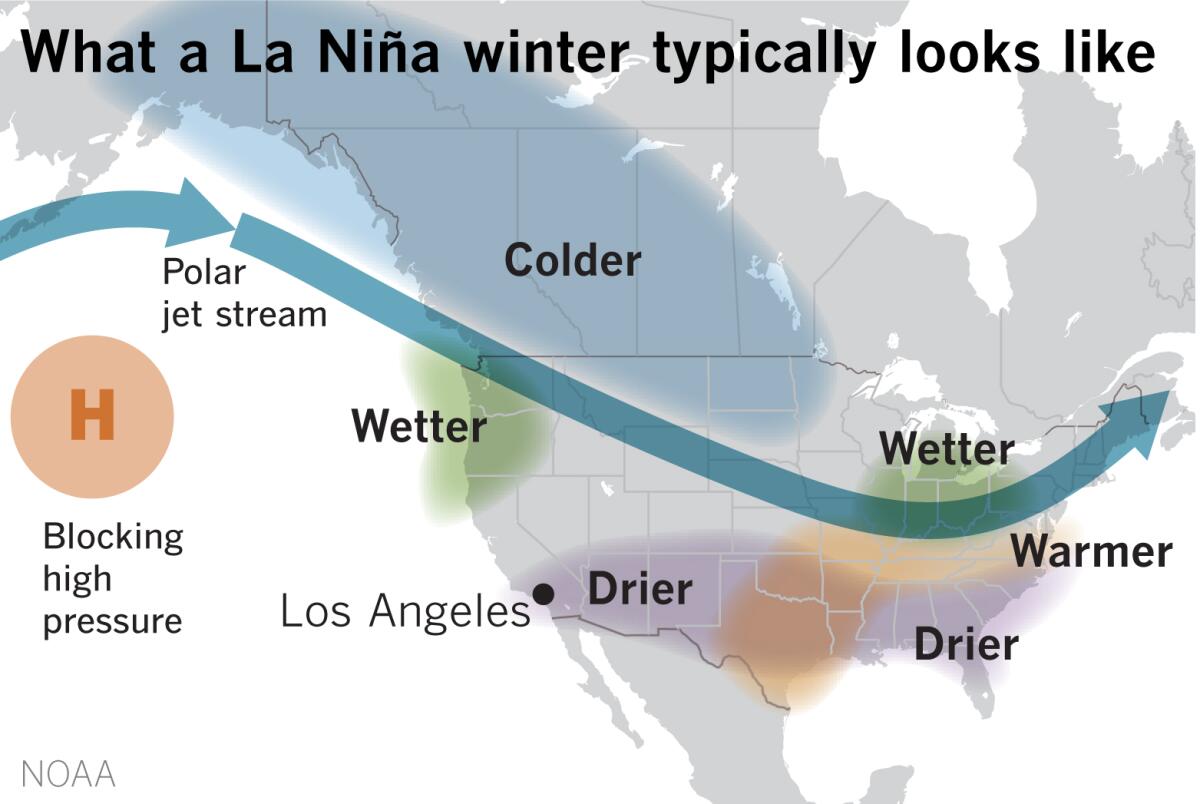

The official outlook from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, released Thursday, favors warmer, drier conditions across the Southern tier of the U.S. and cooler, wetter conditions in the north, consistent with an ongoing La Niña.

A La Niña occurs when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific are below average. Easterly winds over that region strengthen, and rainfall usually decreases over the central and eastern tropical Pacific and increases over the western Pacific, Indonesia and the Philippines. Forecasters now are expecting a strong La Niña with about an 85% chance of it persisting through the winter.

If this scenario unfolds, it would exacerbate drought conditions in Arizona, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and California, and worsen the wildfire outlook for the remainder of 2020 and into 2021.

California is already experiencing its worst fire season on record. After a disappointing rainfall season, much of Northern California is classified as being in severe or extreme drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor released Thursday. Much of the rest of the state is in moderate drought or is abnormally dry.

To the east, big portions of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Texas are in extreme or exceptional drought.

The Southwest has been parched because of a disappointing monsoon season last year and a monsoon that was essentially a no-show this year.

Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, told reporters in a briefing Thursday morning that forecasters don’t know exactly why the 2020 Southwestern monsoon failed so spectacularly.

Arizona and California experienced their warmest April-to-September period in 126 years, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. New Mexico and Nevada had their second-warmest such period. Utah and Arizona recorded their driest period ever during that same six-month stretch. New Mexico had its second-driest and Colorado had its third-driest. Arizona’s newly established statewide precipitation record came in more than 2 inches drier that the previous record.

But since it was one of the driest summers on record, it’s not surprising that it was so hot, David Miskus, meteorologist and drought expert with NOAA points out. There was a lack of moisture and rain to suppress the temperatures during what is normally the warmest time of the year.

People in Southern California count on water from the Colorado River, so drought in the Four Corners region hits home on the West Coast.

Miskus was asked if a dry winter, possibly extending into the Great Basin, will mean a likelihood of more Santa Ana winds through the winter in Southern California.

“Since we are forecasting subnormal precipitation and above-normal temperatures in the Southwest and Great Basin, if high pressure sets up over the Great Basin this fall and early winter — which is possible if the main storm track is across the Northwest — I could see a possibility for more and longer Santa Anas in California,” Miskus said. “But it will matter where that high pressure center sets up, how strong, and if it persists.”

If it’s dry, Santa Anas blowing across dry fuels in the Southland will elevate the fire danger. And cold wintertime Santa Anas are often the most powerful.

Most areas of the West continued to have warmer-than-normal temperatures over the last week, with many areas 3 to 9 degrees above normal, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Extreme northwest California, western Washington and Oregon received some precipitation, but the southern portion of the West saw no relief. Severe and extreme drought increased in southwest Oregon, and extreme drought increased in west-central Nevada.

The Southwest is one of the regions where NOAA predicts the greatest chances for drier-than-average conditions this winter.

“La Niña tends to starve Southern California of its rainfall, but Northern California still has the potential for normal precipitation. So La Niña isn’t necessarily a total bust,” climatologist Bill Patzert said.

“Sea surface temperatures at the equator are starting to drop rapidly, and this emerging footprint of La Niña should have a large impact throughout the United States as well as across the Pacific,” Patzert said. “The prospect of continuing dryness and expanding drought in the American West and Southwest could be counterbalanced by yet another year of excessive rainfall in the upper Midwest, where record water levels in the Great Lakes have caused considerable damage for the last few years,” he said.

“La Niña is one of the largest signals in the climate system,” Patzert said. “It usually doesn’t get as much press as its wet sibling, El Niño, but its impact shouldn’t be underestimated.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.