Court allows Exide to abandon a toxic site in Vernon. Taxpayers will fund the cleanup

A bankruptcy court ruled Friday that Exide Technologies may abandon its shuttered battery recycling plant in Vernon, leaving a massive cleanup of lead and other toxic pollutants at the site and in surrounding neighborhoods to California taxpayers.

The decision by Chief Judge Christopher Sontchi of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court District of Delaware, made over the objections of California officials and community members, marks the latest chapter in a decades-long history of government failures to protect the public from brain-damaging lead, cancer-causing arsenic and other pollutants from the facility.

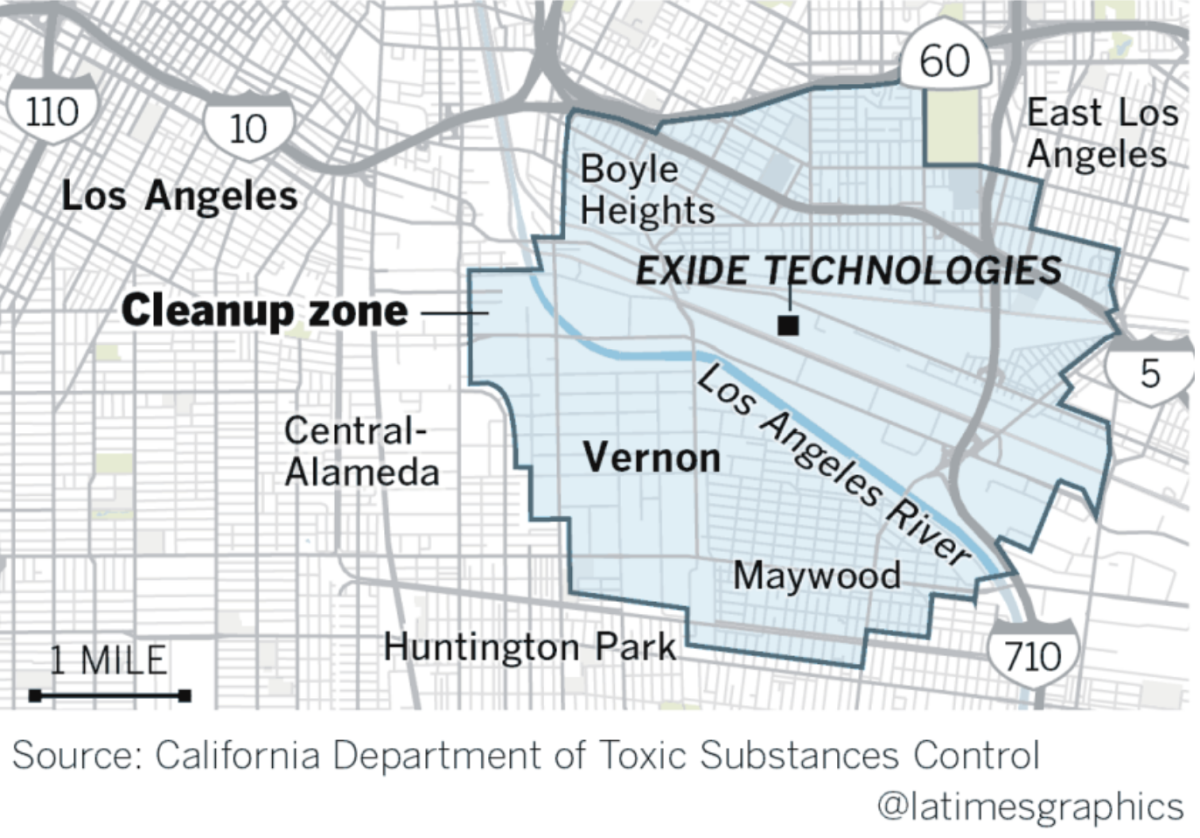

The plan’s confirmation only deepens a fiasco that has subjected working-class Latino communities across southeast Los Angeles County to chronic and dangerous levels of soil contamination and made the area a symbol of environmental injustice.

Community groups have fought for years with the company and its environmental regulators to restrict harmful pollution, shut down illegal operations and clean up the toxic mess. The property’s abandonment compounds the challenges of addressing ongoing health risks to young children and others living nearby, where thousands of yards remain riddled with lead, a powerful neurotoxin with no safe level of exposure.

“I’m frustrated and enraged that Exide is getting away with this, but also by how our system is failing us again and again,” said Boyle Heights resident Idalmis Vaquero, who lives within the residential cleanup zone surrounding the plant. “It’s infuriating. Our federal government is allowing a toxic polluter to walk away, leaving the victims of this contamination to figure out what to do next.”

The decision followed a two-day court hearing with testimony from environmental regulators, company consultants and officers and health experts, much of it about the threats to the environment and the public from abandoning a hazardous facility with the remediation unfinished. The recycling operation, located about five miles from downtown Los Angeles, has not been fully demolished and remains partially enclosed in a temporary, tent-like structure designed to prevent the release of lead and other toxic pollutants.

In his verbal ruling, Sontchi concluded it is not an imminent threat to the public.

“The entire property is not sort of a seething, glowing toxic lead situation,” Sontchi said.

“We have a very dangerous element that will cause long-term health effects” and takes time to accumulate, he said. “I don’t think any of that indicates there’s an imminent, immediate harm to the general public if this property is abandoned.”

State officials blame decades of air pollution from the plant, which melted down used car batteries until its closure five years ago, for spreading lead dust across half a dozen communities, including Boyle Heights, East Los Angeles, Commerce and Maywood. The area has more than 100,000 residents.

A state-led cleanup has so far removed contaminated soil from 2,000 residential properties, as well as as well as parks, day-care facilities and schools. But thousands more have yet to be cleaned in the largest remediation project of its kind in California.

The Trump administration, through the U.S. Department of Justice and the Environmental Protection Agency, supported Exide’s plan, which also leaves behind toxic sites in several other states. Those sites too remain a threat to public health and the environment.

The Justice Department said it received more than 1,000 written public comments in opposition to the proposal, which was released three weeks ago and provided the public eight business days to weigh in. More than 650 people called in to a five-hour public hearing Tuesday, with 125 people giving oral testimony that was “universally and strenuously and sometimes emotionally opposed to approval,” according to a Justice Department filing.

Community outrage did nothing to change the position of the Justice Department, which urged approval of the plan in a court document a day later.

Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a statement condemning the court’s decision, which he said would allow Exide to “evade responsibility for poisoning the homes, playgrounds and backyards” surrounding its facility.

“I am outraged that the federal bankruptcy court let Exide and its creditors off the hook today and decided that lead exposure does not pose an imminent or immediate harm to the public,” Newsom said. “That is wrong, it ignores decades of scientific evidence, and it is a dangerous decision that we absolutely intend to appeal.”

California refused to sign on to the settlement, in which the state would receive $2.6 million in exchange for a broad release from liability. The state has already set aside more than $270 million toward cleaning thousands of homes surrounding the facility with elevated levels of lead in the soil.

If California had agreed to the plan, the Vernon property would have been placed into an environmental response trust charged with cleaning the site. Instead, the company moved forward with a “nonconsensual” plan that would impose a release of liability and abandon the property.

Sontchi’s ruling, however, required that California be allowed to file an administrative claim. Under the decision, the property may be abandoned on Oct. 30, giving the state two weeks to take over the site.

“If they’re unable to transfer this property in the next two weeks, it’s because of their own bureaucracy or their own inability to act,” Sontchi said.

Local elected officials were incensed by the ruling.

“This blatant disregard for the community by Exide, the DOJ and the judge is just another reminder that if you’re brown and poor, you’re disposable,” Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens) said in a statement.

“Today we have witnessed another disturbing injustice,” State Assemblyman Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles) said in a statement. “We will fight this horrific decision and stop the harm that is being done to our communities.”

The facility, which sits on a 15-acre site, remains half-demolished and partially covered in white plastic sheeting, scaffolding, and a negative pressure system designed to prevent the release of lead, arsenic and other hazardous pollutants.

The enclosure requires daily maintenance to prevent tears, according to the state Department of Toxic Substances Control. Earlier this week the department issued a document saying the Vernon site may pose an “imminent and substantial endangerment to the public health or welfare or to the environment,” which officials called a protective measure to give it more power to take steps needed to protect the community from the release of pollution if the site is abandoned.

In a court filing earlier earlier this month in support of abandoning the plant, Exide Chief Restructuring Officer Roy Messing said the site is “of inconsequential value and burdensome” because if not sold or abandoned, it would require “significant expenditures in connection with ongoing decommissioning and remediation obligations ... which would deplete the estate’s limited resources while providing no benefit to the estate or its constituents.”

Messing said in the declaration filed with the court that Exide spent more than $75 million closing the facility and complying with state Department of Toxic Substances Control requirements since 2017 and is currently spending about $750,000 a month to “maintain and secure” the facility.

During the two-day hearing, lawyers for Exide, California and U.S. government sparred over the condition of the site and who would keep the electricity on, pay the contractors maintaining the enclosure around the facility and keep air quality monitors on the facility’s perimeter up and running if it were abandoned.

Peter Friedman, an attorney representing the state Department of Toxic Substances Control, said that Exide was foisting responsibility for the cleanup onto California taxpayers and state regulators. He said that “fugitive dust would be free to migrate off site and families living near the Vernon site could not count on being safe, if current safeguards were removed.”

Attorneys for Exide suggested the Department of Toxic Substances Control could use the $26.4 million the company was required to set aside to keep the tent intact and prevent pollutants from getting out. Toxic Substance Control officials said that doing so would burn through the money quickly just maintaining the enclosure, and that all told, it will cost $72 million to make the site safe.

Exide’s attorneys argued that the company would soon cease to exist and simply no longer has the money to pay for the cleanup, and that the facility would pose no imminent health threat because the enclosure surrounding it remains intact. They also pointed fingers back at the Department of Toxic Substances Control for being slow to act on the health risks at the site and for issuing a determination that it posed an imminent threat only three days before the hearing to approve the bankruptcy plan.

Judge Sontchi asked California’s attorney “how much can the government sit back and not take action to remediate … and then say abandonment is not appropriate because it’s an immediate, imminent, threat.”

At one point during the hearing, Sontchi questioned how exposure to a dangerous element like lead that builds up in the body over time “somehow qualifies as imminent danger when everywhere you go in your life you’re exposed to lead. We all have lead in our bodies. That’s reality.”

Young children are particularly vulnerable to lead because their brains are still developing and can suffer lifelong harm, including lower IQs, learning difficulties and behavioral problems, from even low levels of exposure to contaminated soil and dust, Dr. Gina Solomon, a UC San Francisco professor of medicine and researcher at the Public Health Institute, testified during Thursday’s hearing.

The Department of Justice, for its part, said abandonment was a “last resort” and sought to blame the outcome on California’s refusal to approve the settlement, which was signed by other states where Exide lead-smelting operations have left behind contamination, including Indiana, Texas and Pennsylvania.

California regulators let the facility in Vernon operate with only a temporary permit for more than three decades despite repeated violations of air pollution limits and hazardous waste rules. The plant shut down permanently in 2015 under a deal between Georgia-based Exide and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California. The company, which at the time was undergoing a previous bankruptcy reorganization, admitted to years of environmental crimes but avoided prosecution by agreeing to close and demolish the plant and clean up the pollution.

Exide began working to close and clean the site in 2017, but stopped in March, citing the COVID-19 pandemic. The company filed for bankruptcy protection again in May with plans to liquidate its assets.

California regulators have said for years they were building a case and would go after the company and any other responsible parties to recoup funds for the cleanup. But there will no longer be an Exide to pursue.

There are some existing funding sources that could help sustain the project, including a cleanup fund established in 2016 using fees on lead-acid car batteries like the ones recycled at the Exide plant.

Mark Lopez, co-director of the group East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, said the community pushed for that fee as a safeguard because they knew that the company was likely to use bankruptcy to avoid its cleanup obligations.

“We knew we couldn’t rely on Exide because the legal tools available advantage them and not us,” said Lopez, who lives in East Los Angeles. “It’s a gut punch, and another strike against us. And just because it was anticipated doesn’t make it hurt any less.”

Environmentalists and community groups have long said a real solution requires comprehensive overhaul of the state Department of Toxic Substances Control, which has a history of slow response to urgent health threats and poor oversight of hazardous waste facilities. Gov. Newsom last month vetoed legislation to reform the department.

Jane Williams, who directs the group California Communities Against Toxics, said there are dozens of other hazardous waste facilities in California that the Department of Toxic Substances Control has not required to set aside adequate funds for cleanup, and several other sites where lead smelters may have operated in the past.

“This is going to repeat itself over and over again,” she said. “Exide is just the point of the arrow.”

UCLA law professor Lynn LoPucki, who directs a database of big bankruptcy cases, said California lawmakers are ultimately to blame for the state having “basically no legal rights” to recoup funds for the cleanup through the bankruptcy.

That’s because California law puts environmental obligations behind a host of secured creditors, he said. That’s in contrast to a growing number of states, including New York, New Jersey and Michigan, that have adopted laws that give first priority to environmental liens for the cleanup of hazardous waste.

“If that were true here, then Exide would pay for the cleanup and the creditors would get what was left,” LoPucki said. ”There would just be an understanding that if you mess it up you have to pay to clean it up.”

The state Legislature cannot fix the current predicament with Exide, he said. “But they can prevent this from happening in the next case. And they’re not doing that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.