Isabel Lainez was a familiar face at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center when she showed up one day desperately seeking help.

The 60-year-old often visited the hospital’s courtyard pulling a wheelie bag filled with jewelry that she sold to nurses and other workers on their lunch breaks. Now she was struggling with frequent urinary tract infections that had stopped responding to antibiotics.

She wet herself so frequently — on the bus, in the car, in an elevator — that she started wearing diapers and stopped going out to sell jewelry or visit friends.

A referral to a urologist dragged on for eight months with no appointment. Then a kidney specialist agreed she should be seen, but not for three to six months.

Lainez didn’t have that long. Her adult son woke up to find her body on the floor of his apartment. She had died of chronic kidney disease — still waiting for her appointment.

Lainez is among thousands of patients in L.A. County’s public hospital system who endure long, sometimes deadly delays to see medical specialists, a Times investigation has found.

Doctors, nurses and patients describe chronic waits that leave the sick with intolerable pain, worsening illnesses and a growing sense of hopelessness.

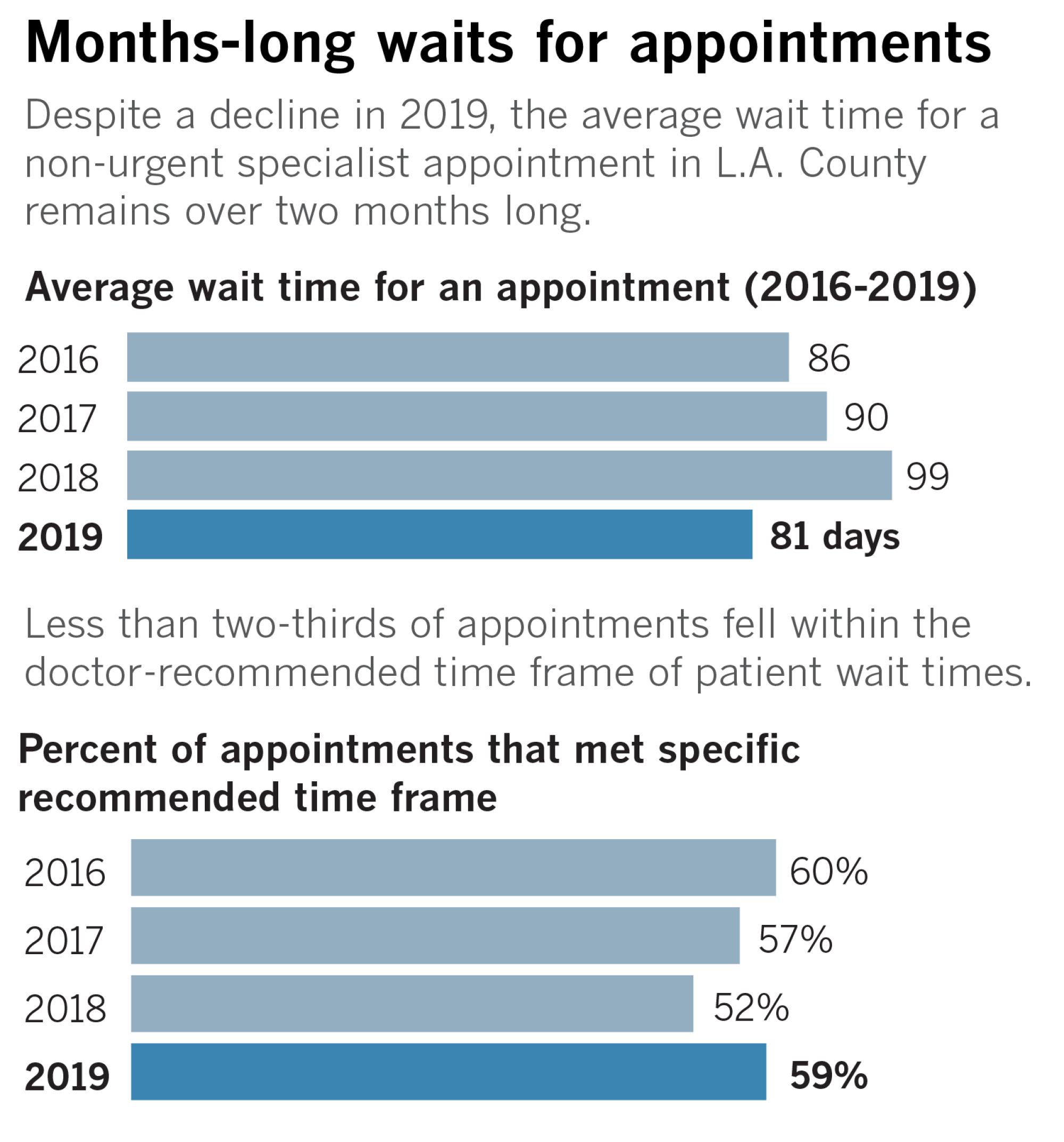

The average wait to see a specialist was 89 days, according to a Times data analysis of more than 860,000 requests for specialty care at the L.A. County Department of Health Services, a sprawling safety-net system that serves more than 2 million, primarily the region’s poorest and most vulnerable residents.

Even patients waiting to see doctors whose prompt care can mean the difference between life and death — neurologists, kidney specialists, cardiologists — routinely fell victim to delays that stretched on for months, according to the data, which consisted of requests from primary care providers to specialists from 2016 through 2019.

When presented with the newspaper’s findings, state regulators launched an investigation into whether the waits violate California regulations.

“It is not acceptable … to have to wait months to access care,” said Rachel Arrezola, a spokeswoman for the state’s Department of Managed Health Care.

The Times’ independent data analysis offers a unique view of non-urgent specialty treatment in one of the country’s largest public health systems. Though it is difficult to directly compare L.A. County’s wait times to those of other healthcare systems, recent surveys and research about specialty care suggest county patients wait significantly longer than elsewhere in the U.S., including the Veterans Health Administration, which has faced scrutiny for its delays.

As part of its investigation, The Times obtained complete medical records for half a dozen county patients, including Lainez. All faced waits of at least three months to see a specialist, and all died of the illnesses they waited to have treated. It wasn’t always clear how much the waits contributed to the patients’ deaths. But in every case, doctors who reviewed the records for The Times said the patient should have been treated sooner and called the newspaper’s findings deeply troubling.

It’s impossible to know how many people have died while waiting for an appointment with a specialist in Los Angeles County’s public health system. County officials said they don’t track that.

But studies show that sick patients are more likely to miss appointments when they face lengthy waits, while those who have serious health conditions — heart trouble, diabetes, cancer — die at higher rates.

“This care is an embarrassment and indictment of our healthcare delivery system,” said Dr. Kevin Kavanagh, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA.

“These wait times are much longer than what I’m accustomed to seeing, and they’re not comparable to other safety-net systems,” said Dr. Kenneth Kizer, who served as director of the California Department of Health Services and oversaw healthcare for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, which is the largest integrated healthcare system in the nation and has faced its own, well-publicized problems with long wait times.

Kizer called on the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to hire outside experts — independent of the Department of Health Services — to review the data underlying The Times’ findings and propose solutions. “The cases you have looked at sound tragic,” Kizer said in an interview.

Except for emergencies, waits to see specialists have almost certainly increased since the start of the pandemic, L.A. County health officials said, as health systems across the country put off non-urgent care in order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus and make room for COVID-19 patients.

Before the pandemic, county health officials publicly touted their appointment scheduling as a success — despite the long waits.

Dr. Christina Ghaly, the county’s director of health services, said her agency has reduced waits in recent years by revamping its referral system and hiring more specialists. Her top deputy called The Times’ descriptions of individual patient cases “inaccurate” and “misleading” but declined to offer any details, citing healthcare confidentiality laws.

More broadly, Ghaly described cases that drag out so long that patients die before they get treatment as “sad and heartbreaking.” No system, she said, is “perfect every time.”

“We strive to provide the best care … and the best outcomes for all of our patients,” Ghaly said. “But our doctors and our nurses and our scheduling staff and everyone else that works in the system are human.”

Ghaly said The Times’ analysis fails to take into account a triage system that schedules appointments when it’s clinically most appropriate, based on a patient’s symptoms, diagnosis and overall health. Specialists designate a specific time frame in which a visit should occur — from less than 15 days to as long as three to six months out — or recommend the patient be given the next available appointment.

After The Times asked about the delays in December, Ghaly sent a report to her bosses on the Board of Supervisors saying that in the third quarter of 2019, patients were seen by specialists within the “optimal” time frame 73% of the time. Many of the remaining patients, she wrote, either chose a later appointment or could not be reached.

“We are not aware of any other health system that even attempts to monitor and meet this level of ideal care,” Ghaly said in the report.

But The Times’ data analysis found that many of those patients still faced long waits. Nearly 40% of the patients Ghaly said were successfully scheduled were given the next available appointment, waiting an average of 112 days. “Next available” is for cases that can wait up to six months, county officials said.

When doctors recommended patients be seen within other, more specific time limits — two weeks, a month, six months — only 57% got appointments within those time frames, the data show.

In an email Saturday, after this article was originally published online, Ghaly accused The Times of “manipulating data” and failing to “present a true and complete view of the life-saving specialty care the Department of Health Services provides to hundreds of thousands of people a year.”

::

The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services has known for years that wait times were a problem in certain departments, such as neurosurgery, but delays persisted despite promises to fix them.

In 2011, Sara Perez was a young mother of three when she was diagnosed with a benign, golf-ball-sized tumor in her brain. A neurosurgeon at County-USC Medical Center said it had to be removed, and she was approved for the surgery.

Despite calls from Perez, the hospital never scheduled the operation. Nearly a year passed.

Eventually, the tumor grew so large it put Perez into a coma. Her 5-year-old daughter found her unconscious on the family’s bathroom floor. Perez died two days later, at the age of 30.

“There’s no reason somebody should die because you can’t put a surgery on the calendar,” said Nicholas Hutchinson, the family’s attorney.

As part of a $1.6-million settlement with Perez’s family, the county promised to take dramatic steps to shorten the wait for neurosurgery at County-USC, including opening a new clinic to treat patients with nervous-system tumors and developing a new process to track patients.

Around the time that the county agreed to the fixes in 2014, Priscilla Duong was driving with her husband when a woman rear-ended them on the freeway. Duong, who was in the passenger seat, immediately felt pain in her back and neck.

She went to a specialist outside the county health system who said Duong needed urgent surgery, but her Medi-Cal insurance wouldn’t cover the $130,000 out-of-network cost.

She tried physical therapy, but that didn’t help. Then in the fall of 2015, a county nurse practitioner referred her to a neurosurgeon. Duong waited over three months for the appointment, at which the doctor noted she had episodes of unsteadiness and worsening numbness in her hands and said she would need spinal surgery.

Duong said she spent the next seven months calling the hospital every week begging for an appointment.

It was “excruciating,” she said.

The pain was so bad, the 38-year-old said, that she couldn’t work, or even get out of bed some days. Frequent dizzy spells led to several falls in the shower. She had to put a chair in the bathtub and let her husband wash her.

Duong finally got a call from County-USC offering her an appointment in September 2016, almost a year after her initial referral.

“It’s a horrible system; yeah, they need to fix it,” said Duong, who is a nurse. “I waited a long time just to have that surgery, but I couldn’t afford it on my own.”

::

A decade ago, a public outcry over lengthy medical delays and patient deaths spurred California to set specific limits on how long HMOs can keep sick people waiting to see a doctor.

The time standards require health insurers — including those offering Medi-Cal, the government-subsidized program that covers about a third of Californians and most of the low-income patients treated by county hospitals — to provide appointments with specialists within 15 business days, or four days in urgent cases.

Because the regulation applies to the insurers and not doctors and hospitals directly, L.A. County health officials said they view the time standards as “guidance.”

The Times’ analysis of specialist appointments found that 88% occurred more than 15 business days after a primary care provider — a doctor or nurse practitioner — made a referral.

“We don’t see the state regulation as our goal or our target,” said Ghaly, the county Department of Health Services director.

Contact our reporters with your story

Have you or a loved one ever faced a significant delay accessing care at an L.A. County public health facility? Are you a healthcare worker at an L.A. County facility who has struggled to get timely care for your patients?

[email protected]

[email protected]

She also pointed to an exemption that waives the 15-day rule if a doctor decides — and notes in the medical record — that waiting longer would “not have a detrimental impact on the health” of the patient.

Dr. Paul Giboney, associate chief medical officer for L.A. County, said the agency’s system of triaging patients based on need renders the state’s timely access code obsolete, freeing medical staff from having to “adhere to some bureaucratic regulation.”

A Times review of thousands of pages of county medical records from about a dozen patients found that they all waited longer than 15 business days to see a specialist and that no exemption notations were included.

Asked about that, Giboney said the fact that a specialist schedules an appointment for two or six months from the time of request means that the doctor believes the wait will not be harmful to the patient.

Cindy Ehnes, who was director of the California Department of Managed Health Care when the agency crafted the regulation, said the exemption was meant to be used as an exception, not the rule.

“For them to say, well too bad, three months is what [the wait] is, certainly defies the intent and meaning of the access regulations,” Ehnes said.

David Kane, an attorney with the Western Center on Law and Poverty, which advocated for the strict time limits, said county health officials were “trying to weasel their way out of these standards in a way that goes against the interests of the patients.”

A national survey in 2017 by Merritt Hawkins, a well-known physician recruiting service, found the average wait for specialist appointments in Los Angeles, and across the country, was 24 days — a fraction of the three-month wait at the county’s Department of Health Services.

After a wait-time scandal rocked the Department of Veterans Affairs in 2014, the federal agency set up a website for patients to check how long the waits are at different hospitals. A recent search showed the average wait for new patients to see a cardiologist was seven days at the facility in West L.A., 26 days in the San Fernando Valley, and 28 days in Long Beach.

For cardiology patients relying on L.A. County’s public hospitals, The Times’ data analysis shows the average wait last year was 89 days.

::

Inside the county’s health system, holdups often begin with routine diagnostic tests that must be arranged by primary care providers before a specialist agrees to schedule an appointment, according to doctors and nurses who work at county hospitals and clinics.

A nurse practitioner who left the county in recent years to work for a large, private healthcare system recalled a gastroenterologist demanding she track down the results of a patient’s decade-old colonoscopy before he would approve a new one. The problem, as the gastroenterologist knew, was that the previous colonoscopy had been performed in Iran.

The nurse practitioner, who spoke on condition of anonymity because she wasn’t authorized to speak publicly about patients, said she was unable to obtain the results from Iran, and the county denied the patient approval for a new colonoscopy.

“We are caring for patients who are the poorest of the poor, and we’re making them jump through these hoops they don’t need to jump through,” she said.

She left the county partly out of frustration at the long delays and difficulty in obtaining specialty appointments for patients, she said.

A nationwide shortage of doctors has made it more difficult for health systems to ensure they keep a robust network of specialists so patients can be seen quickly. At the same time, many doctors are reluctant to accept low-income patients insured through the state’s Medi-Cal program — which pays doctors substantially less in most cases.

One day last year, doctors and nurses at the county’s Mid-Valley outpatient clinic in Van Nuys gathered for a staff meeting at which the facility’s medical director, Dr. Jennifer Chen, rattled off a long list of specialties with wait times of 100 days or more.

Ophthalmology. Ear, nose and throat. Gynecology.

When staffers asked about dermatology, Chen replied: “Oh, we went over derm; derm is terrible. It’s like 140 days,” according to a recording of the meeting reviewed by The Times.

The problem, Chen explained, was the difficulty finding dermatologists willing to work for the county.

As a result, Mid-Valley, which before the pandemic provided care for tens of thousands of patients a year, routed most dermatology referrals to a single doctor who also had a private practice and worked for the county about one day a week. Chen told her staff she was trying to get the dermatologist to start working for the county an additional half-day per week.

Dr. Hal Yee, the county’s chief medical officer, acknowledged that some waits are driven by a staff shortage.

“I don’t want you … thinking that we’re total idiots,” Yee told The Times last year when asked about the dermatology wait for patients at Mid-Valley. “We recognize that [dermatology] is a tough one.”

Other specialties with chronic shortages included gastroenterology, ophthalmology and orthopedics, Yee said.

The county, he said, hired a new director of dermatology to help address some of the shortcomings.

::

Majid Vatandoust had lost about 20 pounds when he went for a checkup at Mid-Valley in early 2014.

Tests found the heating and air conditioning technician was also anemic and had blood in his stool, both indicators of potentially deadly colon cancer.

A nurse practitioner put in a request for a colonoscopy via an internal, email-like messaging system called eConsult.

Instead of filling out a paper referral request, the county’s primary care doctors and nurses sign into eConsult to confer with a specialist about the patient’s condition and whether additional testing or a face-to-face appointment with a specialist is necessary.

County health officials credit the system with helping primary care doctors obtain quick advice from specialists. From before its introduction in 2012 to 2018, the number of face-to-face patient visits scheduled with specialists dropped by about 41%, helping cut appointment times for other patients who need to see a specialist, officials said.

But in interviews with The Times, some county primary care doctors and nurses complained that eConsult seems designed to prevent or delay appointments with overburdened specialists.

Messages to specialists sometimes go unanswered for weeks, said three county doctors who spoke on the condition that their names not be used for fear of retaliation. Such delays were common in the medical records reviewed by The Times.

In other cases, primary care doctors receive an initial response but no further communication, and no appointment, for months.

As is typical, the gastroenterologist who reviewed Vatandoust’s eConsult file never saw the 49-year-old patient before deciding on the request for a colonoscopy, medical records show.

In her response via eConsult, the gastroenterologist said the test used to detect blood in Vatandoust’s stool was “not valid for patients under 50 years old.” She rejected the colonoscopy, and the conversation ended with a notation that read, “patients needs addressed.”

Many health systems in the U.S. begin routine screenings for colon cancer at 50 but perform colonoscopies at any age if patients have Vatandoust’s symptoms, according to experts.

About a year later, Vatandoust returned to Mid-Valley for a chronic cough that wasn’t responding to medication. He saw three doctors, each of whom noted in his record that he had been denied a colonoscopy the year before when he was 49 — despite the worrying symptoms.

This time, Vatandoust was approved for the test, but county medical staff had not reached him to schedule an appointment more than a month later, records show.

Not long after that, Vatandoust was in excruciating pain and unable to defecate. A worried friend, Maryam Kamy, took him to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

There, doctors found a large tumor blocking his colon. They told Vatandoust that the cancer had spread to other organs and that surgery was futile, Kamy said.

They were both in shock at the diagnosis, Kamy said, and she broke down in tears when the doctors delivered the grim prognosis — the cancer would kill him. Vatandoust died of colon cancer in August 2017. He was 52.

“It’s so ruthless,” Kamy said of the county’s refusal to give her friend a colonoscopy when his chances of survival would have been better. “He was very young to lose his life for just a little bit of money.”

Vatandoust’s case is a classic example of how not to use eConsult, said Dr. Robert Wachter, a professor and chair of the Department of Medicine at UC San Francisco. The communication tool, he said, offers a good way to obtain a quick consultation with a specialist but should not be used as a substitute for critically needed tests or face-to-face appointments.

“The combination of blood in your stool and anemia gets you a colonoscopy — I don’t care if you’re 12,” Wachter said. “It’s a mistake, and a tragic mistake.”

Citing patient privacy laws, county health officials refused to explain why Vatandoust wasn’t given a colonoscopy after showing the classic warning signs of colon cancer in 2014.

After The Times asked about Vatandoust’s care, Kamy said she received a call — two years after Vatandoust’s death — from a county health official offering an apology.

“It doesn’t do anything for me; it doesn’t heal me,” she said. “I needed their help when Majid was alive, but they didn’t care about him then.”

::

For Isabel Lainez, frequent urinary tract infections meant she was no longer able to sell her jewelry in the courtyard outside County-USC hospital or any of the other regular spots she used to visit around the city.

As she waited to see a kidney specialist in early 2016, the average wait time for an appointment at the County-USC nephrology clinic was 114 days, according to The Times’ data analysis.

Her incontinence got so bad that she wouldn’t leave the house. When she could no longer reliably make it from her bed to the bathroom, her children bought her a portable toilet to keep by her side.

“I felt hopeless,” said her daughter Jessica Avitia. “She was never getting the help she needed.”

Lainez’s son, Jerry Solis, had just crawled into bed after an overnight shift in a fish warehouse when a family member woke him and told him he’d better check on his mom. He found her body cold on her bedroom floor. She was 61.

After The Times asked about Lainez’s care, Dr. Arun Patel, the director of patient safety and risk management at the L.A. County Department of Health Services, met with Avitia and Solis and acknowledged that “it did take a while” to get their mother an appointment with a urologist. Patel attributed the failure to provide an appointment to a “miscommunication” between the nurse who made the referral and the urologist who responded.

“That’s not something we think is OK,” he told them in January. “I’m as bothered by it as you might be.”

Patel said Lainez’s medical records indicated she had only a mild kidney problem. A specialist made a “judgment decision” that she could wait three to six months, he said.

“How bad does it have to get for her to be seen?” Solis asked.

“For her to be dying literally in front of you?” Avitia asked.

Patel told them he did not know what killed Lainez but speculated that it might have been a heart attack.

Her death certificate, which is signed by a county physician, lists the immediate cause as “chronic kidney disease.”

About a month after Lainez’s death, her family held a viewing that drew nearly 100 people. So many friends turned up, Solis recalled, that they filled the mortuary and spilled outside.

Half a year after the siblings placed their mother’s ashes in an urn, someone from the county scheduling center tried calling Lainez with good news, her medical records show.

An appointment was finally available.

Times staff writer Ryan Menezes contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.