We absorb the images — the charred remains of a homeowner’s paradise, a sweeping natural vista left blackened by towers of flame — and they are startling in their reality.

And we can’t help but wonder: Just how do these photographers get so close? What runs through their minds? What risks do they take?

For Times staffers Kent Nishimura and Brian van der Brug, meeting the challenges of covering the California fires requires passion for their craft along with perseverance. They follow their own playbook, guided by instinct and years of dashing to heartbreaking assignments.

The recent West Coast blazes cap a fire streak that’s been unprecedented in its destructiveness and may grow worse in years to come.

Here, we go behind the scenes with Nishimura and Van der Brug to better understand what makes their pictures stir our emotions.

You’ve covered many fires before. How is this time different in its cruelty and intensity — and how must you adapt to get the job done?

Nishimura: This is my third fire season, and it totally feels like they get bigger and bigger. To stay ahead, we [photojournalists] started teaming up to look out for each other and keep each other safe, especially in these mountainous regions where things can get sketchier. That’s what happened at the Creek fire. It used to be everybody would travel on their own. We’re competitors.

At the SCU Lightning Complex fire, there was a photographer from AP, Reuters, San Francisco Chronicle and myself. We were telling each other: “Hey, hey guys, look out.” There was a tree with embers, burned from inside at the base, and it could fall over at any moment. Falling trees are deadly, if not more deadly than the fires itself, just because they’re so unpredictable. Hearing this constant sound of trees crackling and shattering can be haunting. Imagine these redwoods several hundred feet tall that have crashed across the roadway. It sure stops you from getting places.

Van der Brug: The job of covering wildfires has changed as our climate has changed. Looking back 10 or more years ago, fires were seasonal. I’d take my fire bag with protective Nomex clothing, helmet and goggles off a shelf in my garage and load it into my car along with gallon-sized bottles of water at the first forecast of Santa Ana winds and September heat. Shortly after New Year’s Day, it would go back on the shelf until late summer or fall, when fire season came back around. Today, it’s always fire season. The cumulative effects of climate change, record-high temperatures and drought mean a catastrophic fire can start anytime. The fire bag stays in my trunk all year long.

Can you share any anecdotes about close calls, a particular shot made in life-threatening circumstances — perhaps when you were trying to get a better picture or running for your life?

Nishimura: This past Labor Day weekend, I was with Marcio Sanchez from AP and we saw the Laguna Hotshots [an elite forest-fire crew] out of the Cleveland National Forest getting ready to do structural protection for plants. At one point, the wind started kicking up, there were really large ember wash being blown into the air, and I saw the Hotshots begin to leave the area. That’s a sign, when firefighters are leaving, you should be leaving too. So we followed them. We decided it wasn’t worth it anymore to stay there. And there was only one way out of Big Creek, but with a wall of smoke blocking us — that’s probably the most worried I’ve ever been at a fire.

I couldn’t see in front of me. I just had to navigate on gut alone.

What’s the process when unexpected fire news interrupts your day?

Van der Brug: When a wildfire takes off locally, many of us will just drop what we’re doing and go cover it. Other times, an editor will call and ask us to go. I was recently assigned to the Bear fire in the Plumas National Forest near Oroville. I’d worked on a daily assignment in L.A. most of the day and hit the road in the late afternoon for the 450-mile drive to the fire line.

On the previous night, the fire raged through the small mountain community of Berry Creek. I saw incredible images of the devastation online from freelance photographers Noah Berger and Josh Edelson. The two Bay Area photographers are some of the best in the business. They often pair up to work wildfires, share information and watch each other’s back. I messaged Edelson on the way north. He said he and Berger were headed home after working the fire for 31 hours straight. He said I might still find some fire on the forest but thought it was laying down after burning through to the shore of Lake Oroville. He gave me a tip: Check out Lumpkin Road, just over the Enterprise Bridge.

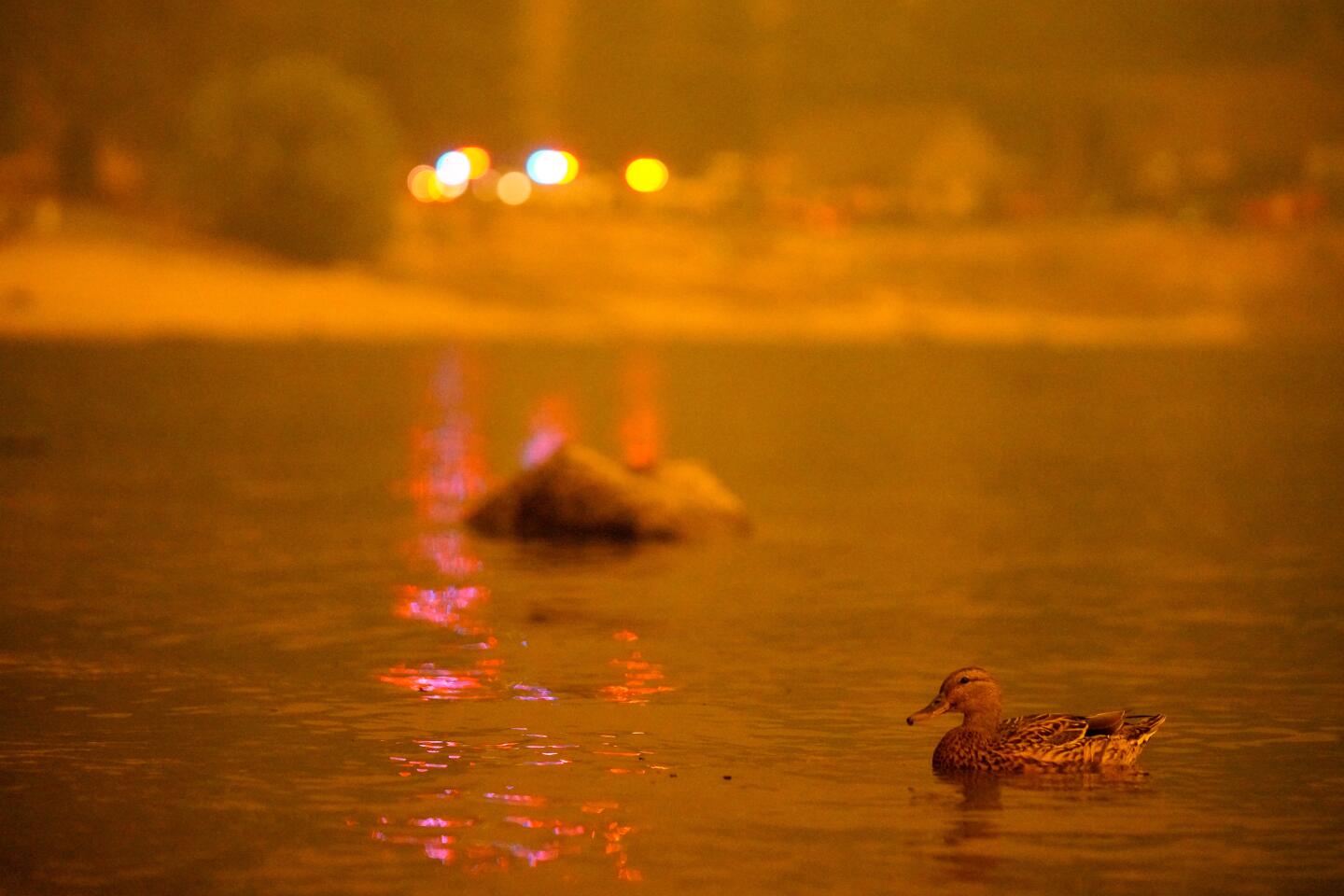

At first light, the devastation over the bridge was masked by thick smoke, not unlike the Central Valley’s tule fog, limiting visibility to 30 feet. Driving slowly, the view through the haze revealed smoldering remnants of homes, some with only stone chimneys still standing. Propane gas shot out of broken pipes, with orange flames dancing through the air. Burned-out shells of cars and trucks were in almost every yard and on nearby roads. Aluminum from melted wheels left gleaming rivulets of molten metal alongside them. The same scenes unfolded for several miles — torched mailboxes, fences, a “Keep America Great” campaign sign melted in the heat of the flames. Around a bend in the road, the charred skeleton of a utility pole, wires and a transformer blocked further passage.

This has been a year to outdo other traumatic years, from the COVID pandemic to mass demonstrations to exploding firestorms. Describe the drama of one of your missions.

Van der Brug: Although it’s our goal to get to the fire front and document firefighters battling a blaze, it’s not always possible. Fires move according to weather and terrain. They often burn in inaccessible areas. The Bear fire, which was started by lightning in August, had been smoldering for weeks before it was driven by fierce winds into the mountain communities near Lake Oroville. A dense layer of smoke prohibited air resources from fighting the fire, and with it the “air show” that accompanies that effort. In a day, the heavy action was over; the time to photograph 50-foot walls of flames had passed. But hazards in the aftermath of a fire can be just as dangerous as active fire.

In rural areas, you are often on your own. Gone are residents, evacuated days earlier, as well as firefighters who have moved on to the next hot spot. Although there’s no active fire, it’s no time to let your guard down. Fallen utility poles, wires, burned trees, narrow dirt roads coupled with no cell service can get the unprepared into trouble. And just because a fire is out doesn’t mean it will stay out. Late into one evening when I was safely back at my hotel near Sacramento, a notification on Twitter came in:

#BearFire/#NorthComplexWestZone - Heavy fire impacting Stringtown Rd w/ a handcrews bus now fully engulfed, no injuries to any personnel & all firefighters are accounted for. Fire crossed Stringtown & is now running parallel w/ Maidu Run.

The Bear fire came roaring back.

How do you take care of yourself and recharge?

Nishimura: When I’m at a fire, I make sure I get a good amount of sleep to keep me going. In between fires, I try to unwind and find something relaxing, like reading a book or binge-watching a show on Netflix, something low-energy. I stock up on trail mix and protein bars — when you’re spending 16 to 20 hours each day on the fire line, or driving around looking for things to photograph in an evacuation zone, you make sure you bring your own food and a ton of water.

But you’re constantly drawn to the work. Sometimes, we’re bone-tired but we can’t let the danger discourage us. I try to focus on the task at hand, much like the firefighters who are carrying heavier equipment. These guys are working tirelessly. It’s pretty inspiring that they’re putting themselves at risk saving towns, saving people’s homes while totally exhausted. At some level, I think: “Hey, if these guys can do it and they have a much more serious load, so can I.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.