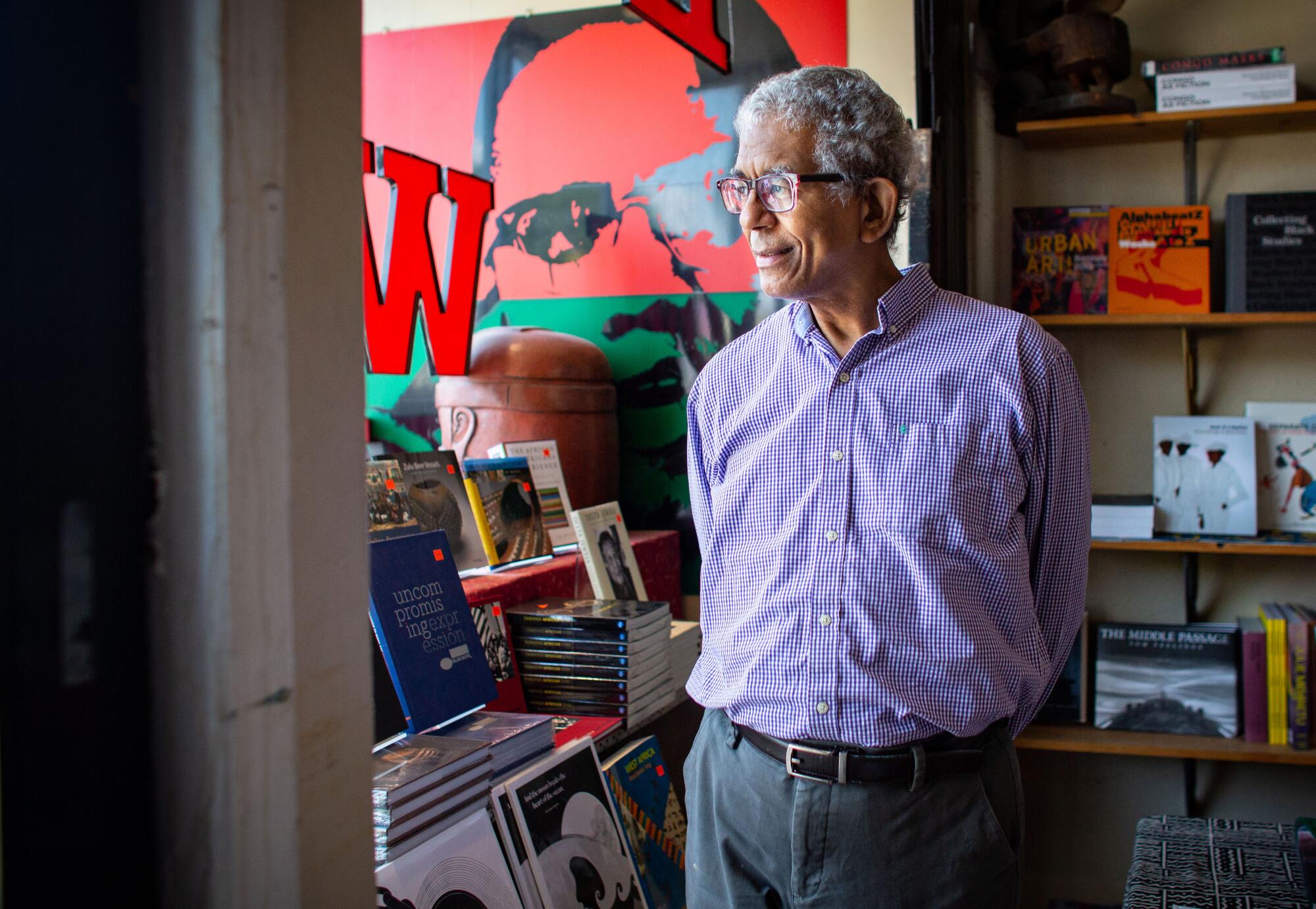

From the porch of his namesake shop in Leimert Park Village, Sika Dwimfo, 79, has watched the community absorb the tides of history.

Sika, who is known to everyone in the neighborhood by his mononym, can often be found sitting in a lawn chair in front of the store, greeting passersby and observing the happenings in Leimert Park as he’s been doing for nearly 30 years.

He’s had a front-row seat to major events including the 1992 riots, economic downturns, changing demographics and more recently the rapid gentrification that some fear could taint the community’s unique identity as a cultural hub for the Black community.

But in the midst of the global pandemic and the boiling point of racial tensions occurring worldwide, Leimert Park is experiencing a revival.

After closing his store — which is known for nose piercings, African imports and handmade jewelry — for two months due to the coronavirus, Sika has been receiving his best sales since opening in 1992. Many of his neighbors have been experiencing a similar growth.

Now, when Sika looks out to the village along Degnan Boulevard, he hears the sounds of reggae music blaring from car stereos for the entire block to hear. He sees people dining outside and lining up to enter stores that have reached capacity. And he watches a steady flow of cars filled with potential customers come in and out of the area throughout the day.

“It’s like a new beginning to a cultural revolution,” Sika said.

The police killing of George Floyd and the surge of activism around Black Lives Matter has suddenly made the shopping district once again a destination for discussion, gatherings and commerce. And the movement’s push to support Black-owned businesses has also attracted Black shoppers who are intent on spending money in their communities.

“I always want to support other Black entrepreneurs,” said Terri Thomas, who was shopping in the village on a recent Saturday afternoon.

“A lot of the things you see happening with gentrification, it’s like really heartwarming that the Black community still has something that they can cherish, and other people too,” she added. “It’s not just for Black people. I think it’s important for everyone.”

Netez Brown trekked on least three freeways via a ride-share service from North Hollywood to purchase sage from Sika and to buy a fruit smoothie from Harun Coffee on a recent Monday afternoon.

“I think it’s important that we bring the revenue back into our community,” she said about Leimert Park. “I’ve definitely been more intentional about it lately.”

The community’s annual Juneteenth festival also drew newcomers to a place where they could unapologetically celebrate their Blackness and for others to learn about the culture. The event brought nearly $600,000 to the neighborhood, according to Tony Jolly, one of the organizers.

Stylist and costume designer Zerina Akers added several Leimert Park businesses to her curated directory of Black-owned businesses featured on Beyoncé’s website. Several publications — including The Times — have also created similar lists. In a newly released music video called “Entrepreneur,” Bey’s husband, Jay-Z, and Pharrell also gave a nod to several of the business owners in the area.

The recent surge in business has sparked a new energy in Leimert Park, which has been struggling financially in recent years amid construction of the Crenshaw Metro line, the overall decline of retail and creeping gentrification. But some wonder if it’s a temporary improvement.

Thousands showed up for Juneteenth festival in Leimert Park, a seven-decade tradition

Earl Ofari Hutchinson, president of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable, said the shopping district will need to make crucial changes in order for the community to continue to thrive.

“The Black Lives Matter movement gave a temporary spurt to and interest in Black businesses in Leimert Park,” Hutchinson said. “But it was fleeting and not in and of itself sustainable for the area’s business to grow.”

He added: “The businesses in Leimert Park for the most part suffer the same handicaps that all small businesses do. That is a chronic lack of capital, a stable and growing customer base, and wide promotion. Survival and growth for Leimert Park businesses depend squarely on providing good products, good promotion, good marketing and a good, stable clientele.”

Akil West opened Sole Folks, a sneaker boutique, Black marketplace and incubator for aspiring designers, in August. He’s the new kid on the block, but he already recognizes what some of the veteran owners have been saying. The empty storefronts need to be filled.

“They’re only investing in their real estate. They’re not investing in the community,” said West, who grew up in the area. “If these people continue to be allowed to lapidate the streets of Leimert Park with vacancies, we’ll never get over that hump.”

The future of Leimert Park has long been a point of much debate in L.A.’s Black community. The population of Black people in Los Angeles has declined over the last 30 years, and some historic business districts like Central Avenue have seen an influx of Latino residents. Leimert Park and the surrounding Crenshaw area remain a commercial hub for Black people, but anxieties about gentrification have sparked questions about what will come.

Some feel that it’s up to Black business owners to take ownership of the community’s fate.

“This area is going to change within another year,” said James Fugate, co-owner of landmark Black bookstore Eso Won Books. “It’s becoming more of a place where people of all races feel comfortable living here and people are going to want services.”

He added: “I think we have to continue to emphasize that we are the ones that control our destiny. If we want more Black businesses, we have to invest in our own community, and that’s what it takes.”

Many business owners like Adé Neff, who runs Ride On! Bike Shop/Co-Op, have been in talks with others about creating a community coalition and a merchants’ association to focus on next steps for the community. But like a village, he said the business owners will have to work together to create permanent change.

“Intentionality is everything,” Neff said. “We’ve built Black wall streets before in other cities, so there’s no reason we shouldn’t be able to do it again.

“It’s a new era of vibrancy in Leimert Park,” he added.

For Marlene Sinclair-Beckford, who opened Ackee Bamboo nearly 15 years ago, part of that change needs to include the implementation of new guidelines and regulations to be upheld in the community.

This is “important to keep us stable and to keep us focused,” she said. “It’s great that it’s open to everyone, but there has to be policies set in place, and we all have to follow those policies in order for us to survive.”

But despite valid concerns about Leimert Park’s future, most store owners are just grateful that they’ve been able to stay afloat during the pandemic, and they have been making necessary adjustments to keep up with the times.

“We’re all being blessed,” Sinclair-Beckford said about business owners in Leimert Park. “I’m grateful for that.”

After locking up his shop at the end of the day, Sika and his daughter, Milan, turned their lawn chairs to face Hot and Cool Cafe, which was holding an outdoor jazz night in a decorated alleyway.

As a six-piece band played backup music for open mic performers and attendees danced in the street, Sika sipped on a glass of wine and bobbed his head to the tunes that traveled throughout the block. He reveled in the moment, which he said reminded him of Leimert Park during its heyday, sensing it would last.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.