Immigrants, hit hard by the pandemic, are sending even more money back to Mexico

Silvana Alaníz, owner of the tiny El Rincón restaurant in San Ysidro, works from dawn to dusk alongside her entire immediate family. Even her 10-year-old daughter helps serve the clientele, who often wait in lines that wrap around the block for Alaníz’s locally famous menudo.

“We have five kids, and they all cook,” she laughed. “They all help here. They spend their summer days in this restaurant. I think that’s one of the reasons we’ve been surviving.”

But the restaurant supports not just her family in San Ysidro. Every month, Alaníz, 43, also sends money home to her father in Mexico.

The COVID-19 pandemic has slammed many of the immigrants who bused tables, picked crops and stood shoulder to shoulder in factories. But many have kept working in what are considered essential — if risky — jobs. And through the summer, Mexican immigrants like Alaníz living in the United States sent home record sums of money to their families, defying predictions that so-called remittances would plummet.

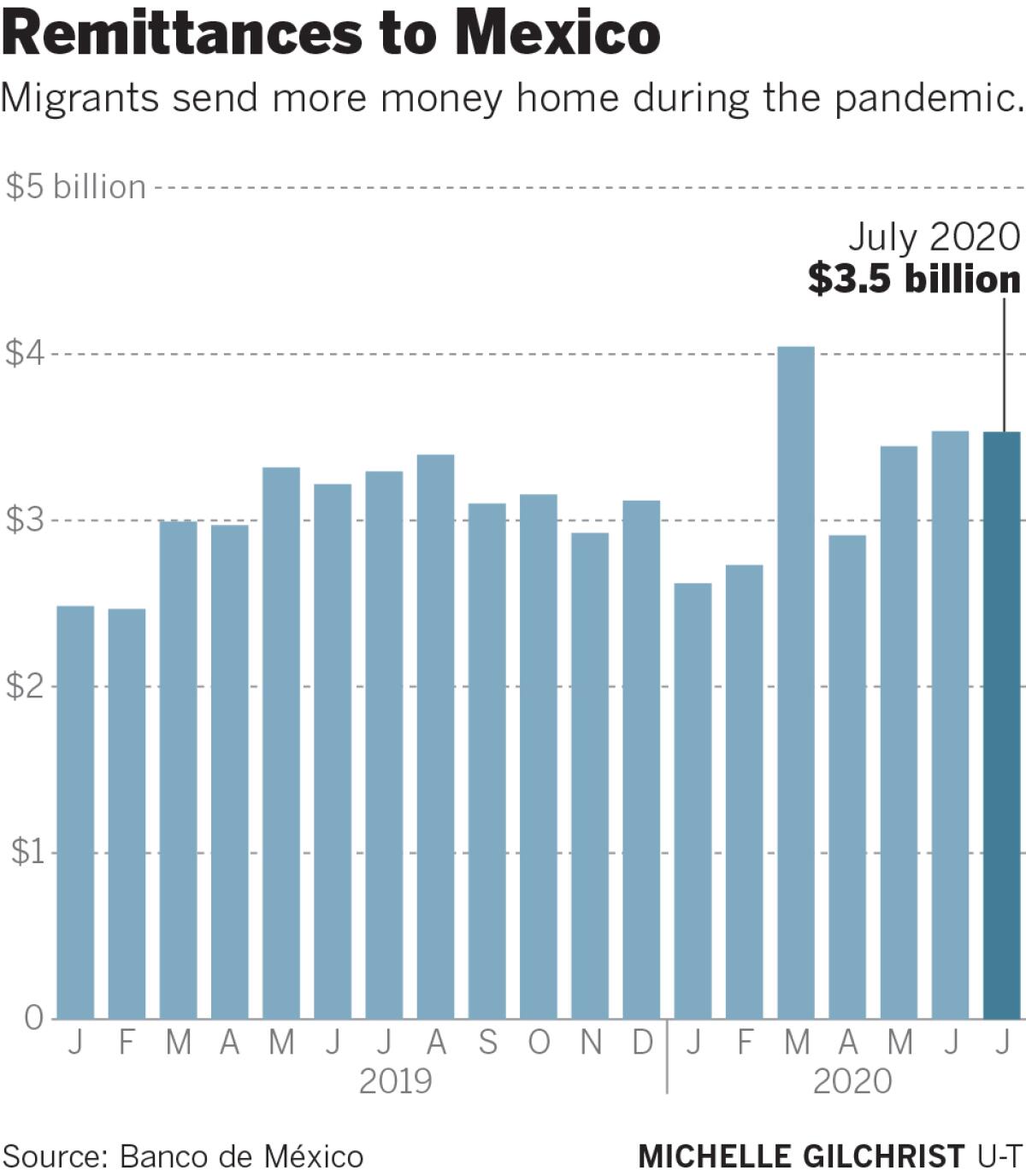

Mexico received $3.53 billion in remittances in July — most of it from the U.S. — a 7% increase over the same month in 2019, Mexico’s central bank data showed.

Even as the unemployment rate in the United States soared to 14.7% in April, and the World Bank predicted global remittances would tank by about 20%, Latinos working in the United States baffled economists by sending more money home to Mexico and Central America than ever before.

In March, remittances hit their highest level since record-keeping began in 1995, surging 36% to $4 billion. July was the third-highest level on record, central bank data showed.

The funds are a major help for the Mexican economy and low-income families across the country, supporting approximately 1.5 million families, according to the Mexican federal government.

“I think, initially, it was a surprise,” Ismael Plascencia, faculty director of business at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, said of the rise in remittances. “But it makes sense. People in the United States are very worried for their families in Mexico — for their health — that’s why they are sending more money.

“Workers in the U.S. made a great effort because they know that their families in Mexico do not have access to good health systems,” he added.

Alaníz, the owner of El Rincón, said that in Mexican culture, families don’t cut off their loved ones in times of hardship.

“That is not an option. That is just the culture. We don’t do that. For Mexicans — for Latinos in general; parents, family, grandpas, even uncles sometimes — the whole family stays together,” she said. “We stick together.

“We use adversity not to separate but to get closer together.”

Latinos are more likely to work in frontline jobs, ride public transit, have underlying conditions and live in multi-generational homes — all considered risk factors for the coronavirus.

In San Diego County, Latinos make up 34% of the population but account for 63% of total coronavirus infections and 45% of deaths from COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, county government data show. In California, they are about 39% of the population but make up 60% of cases and 48% of deaths, according to the state Department of Public Health.

Experts say amid the pandemic, immigrant workers are more likely to be considered “essential workers,” often doing low-paying jobs that others won’t in construction, maintenance and service sectors.

“Other people have a choice,” Plascencia said. “They don’t have a choice. They are the most vulnerable because a lot of things they do are considered essential, like cooking and agriculture. They are willing to do the jobs others are not, and that was true before the pandemic, but now with the pandemic, it’s even more true.”

To send money home, workers in the United States often go to a business that performs international payment services or transfers, such as MoneyGram or Western Union. The businesses usually charge a fee, and the exchange rate of U.S. dollars to pesos is usually slightly worse than is offered in banks.

The vast majority of remittances are done by electronic transfer. Of the $3.53 billion received by Mexico in July 2020, $3.49 billion was in electronic transfers, $24.9 million in cash and kind, and $12 million in money orders, data show.

The average remittance in the period from January to July was $337, 4.3% higher than in the same period in 2019.

Outside the Western Union on San Ysidro Boulevard, people were reluctant to speak about the process.

“They’re afraid [to talk],” explained Alaníz, whose parents used to own a money transfer business. “People are afraid if they put their real address maybe ICE is going to come get them, or even though it is legal to send money home, they’re worried maybe someone will think they’re doing something wrong.”

At the money transfer outlet Elektra in Tijuana’s Plaza Carrousel, Lisa Garcia, 44, said both her children in Orange County are working any and every job available so they can send funds for her medical care and rent.

“Thank God for family,” she said. “Right now, my son is just doing a little bit of everything. A little construction. He drives Lyft. Whatever work he can find.”

Though she does not have the coronavirus, Garcia has been sick with flu-like symptoms. So the maquiladora where she worked didn’t want to take the chance she was spreading the disease, Garcia said. She’s among the 12 million people in Mexico who have lost their job during the pandemic, according to the federal government.

Migrant workers in the U.S. sent home $330 million to Baja California between April and June 2020, according to the latest figures from Mexico’s central bank. Though breakdowns by municipality were not available, Tijuana is often the city in Mexico that receives the most remittances. Tijuana residents received $476 million from Mexicans living abroad in 2019, according to a BBVA Research report.

The economic downturn has forced many of those living in the U.S. to dig deep for their contribution back home.

Business at the colorful El Rincón has dropped off about 60%, Alaníz estimated. That hasn’t stopped her from sending money to her dad in Tijuana, or giving back to her community.

Alaníz knows what it’s like to not have food on the table. So, each week, she and her team prepare 60 meals that are distributed mostly to seniors as part of a program of the community organization Casa Familiar.

She believes when you give back, you get back.

Indeed, the organization arranged for a local artist, Michelle Guererro, to paint a giant mural on the side of her restaurant. The painting is of a serpent giving a flower to the moon.

Fry and Mendoza write for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.