The Latino wealthy — a new breed

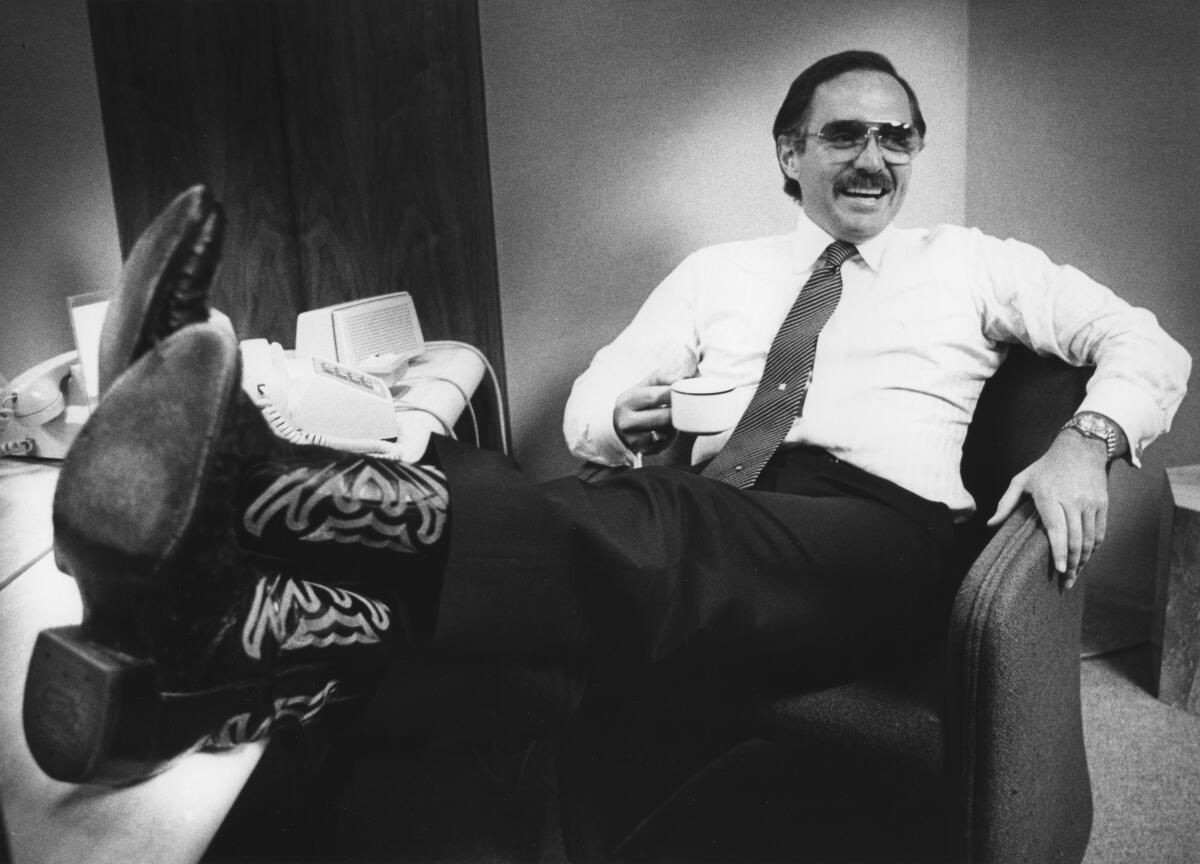

Dan Pena, arms swinging, fingers snapping, strode down the polished corridor of an oil company headquarters in west Texas with the intensity of a matador entering a bullring. You could almost hear the trumpets.

Trailing him was an attorney he had flown in from Los Angeles and two accountants from Fort Worth, each solemnly locked in the mission at hand: to make Pena, as he says, “one damned rich tortilla.”

Already a wealthy oil broker (last year $50 million in gross revenues), Pena was bidding to buy an oil refinery and petroleum terminal of his own from a company that insists that its name, for now, be kept secret.

“I want to be another Exxon,” Pena said, turning a corner, heading down the stretch. He is 37, 6 feet, 1 inch tall and handsome enough to be a movie star. “Or at least another Armand Hammer.”

He opened the door of a meeting room and came face to face with a smooth, sweet-talking Tennessee preacher-turned-lawyer-turned oil company negotiator.

“Well,” the ex-preacher said, with a courtly bow, “our own little army of min-or-it-ies. You bring about 80 million pesos with you, Mr. Peen-yah?”

It was a good-natured needle offered in a drawl as sweet as a spring morning in Memphis, but Pena was up to it. He assumed a poor-Mexican stance, shrugged and shook his head.

“Eighty million pesos,” he said with a low whistle. His accent was mock-Chicano. “That could sure buy a lot of tacos . . . .”

It was a scene classic among the tiny but growing number of Mexican-American millionaires who, with tenacity and style, are playing the Anglo angles on the way to megafortunes.

“We want freedom and we want impact,” a Chicano lawyer explained, “and one way to get them is through economic independence. We’re using what we have. God have us lemons, we’re making lemonade.”

Dan Pena is one of those who has elevated lemonade-making into an art form. Tough, smart and demanding to be heard — even his quick, flashing smile is noisy — Pena seemed destined to be rich.

His family moved him out of a barrio near Chavez Ravine and into upper-class Encino when he was 10 so he would be raised among high achievers. When other kids were on the street, Pena was taking tennis lessons. And dance lessons. And golf lessons.

Dan Pena is a dream of ethnic alchemy that, in his case, has created a golden Chicano.

No one seems to know exactly how many chicanos de oro there are in sprawling Southern California, but the feeling exists that there are probably more now than there were a decade ago.

The 1980 Census discovered 10,717 “Spanish origin” families in Los Angeles County whose annual income topped $50,000 compared to 6,798 black families and, disproportionately, 139,126 white families.

Nationally, the percentage if Spanish-origin families with that income has risen during the last 10 years from 0.3% to 3.5%. of the 3,305,000 Latino families in America, 115,675 earn more than $50,000 a year.

“We’re the flip side of the vato loco (crazy street guy),” a wealthy Chicano industrialist said, “and no one hears much about us yet. But they will . . . .”

This is their story, summarized in the lives of three rich Mexican-Americans.

Dan Pena is one of them. The other two are Manuel Caldera, 51, whose Hawthorne-based Amex Systems Inc. is probably the largest minority-owned high-tech company in the United States ($60 million in gross revenue last year), and cinematographer John A. Alonzo, 48, whose 47 films — “Chinatown,” “Norma Rae,” “Sounder,” “Harold and Maude,” “Lady Sings the Blues,” “Blue Thunder” and others — have not only made him wealthy but also a legendary figure among striving young Mexican-Americans in Southern California’s giant film industry.

Each represents, in his way, what it takes for a Mexican to make it, and make it big, in an often-hostile Anglo society. Each, as Caldera says, came to realize long ago that “There’s more to life than picking lettuce.”

::

“Times is money,” Pena was saying between telephone calls in his hillside Palos Verdes home. “I learned that at the beginning. I used to sleep in the office so I wouldn’t waste time. One of the first things I did when I started making money was get a phone in my car. My company headquarters is only 2 ½ minutes from here.”

He put a stick of gum in his mouth. “Two and a half minutes exactly.” He was sitting on the edge of a couch in the “sports lab” of his big ocean-view house, a room “dedicated to me.” There are Dan Pena pictures and Dan Pena plaques on the wall, along with a photograph of his hero, the late John Wayne. The “lab” also contains a press bench, weights and other exercise paraphernalia. Pena squeezed a hand grip as he talked and chewed gum. Sometimes he fiddles with Silly Putty. His energy is combustible, his manner kinetic.

A television set in the room was turned to a channel that reports stock market quotations throughout the day. A set in the living room was on the same channel. So was one in the master bedroom. All three go simultaneously as long as Pena is in the house, the muted audio of stock quotations droning in the background like a lullaby of Wall Street.

“I leave the lights on all day too,” he said, trying to explain his own eccentricities. “I don’t know why. Sometimes Linda (his wife of 10 years) will change the television station when I’m not in the room. When I come in, I change it back.”

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

They have a 14-month-old son whom Pena adores. One of his goals is to spend more time with the boy. He’ll block out the hours, schedule the hugs and list them with his priorities . . . in between flights to New York, London, Tel Aviv, Dallas—150,000 miles a year, going somewhere.

On this particular day, he was just back from Texas and edgier than usual. “If the oil refinery deal goes through,” he was saying, “I could either be rich beyond belief or lose everything. But you’ve got to dare.” He glanced at his $8,000 Rolex watch. “This will take time. They’re playing a waiting game.” He smiled. “A Mexican standoff.”

Pena’s mother was born in Mexico, his father in New Mexico. His dad, a former Los Angeles cop, teaches criminal justice at East Los Angeles Community College. His mother, who is part Austrian and part Spanish, gave her son blue eyes and white, even teeth.

“I was never raised as a Mexican,” Pena said, a defensive shade to his tone. “Therefore, I don’t try to market my Mexicanism. My parents took me out of the barrio so I would achieve. It had an odd effect. While they’re proud of their roots, I don’t think about mine.”

He knows racism is out there, he says, but he has never allowed it to darken his life. He won’t be picked on. “I’m not a victim of the sombrero syndrome. Don’t try walking on Dan Pena.”

Pena doesn’t know if being Mexican-American has done him any good in business. “I didn’t even think about being a minority until three years ago. I was at a campaign party for Jimmy Carter. Someone asked what kind of ‘set-aside’ I had. It wasn’t until later I discovered it’s a special dispensation on government contracts given the socially or economically disadvantaged.

“It flashed through my mind, ‘How can I make money on this?’ I never did. They just couldn’t see me as socially disadvantaged.”

Pena traces his desire to make money to an Army hitch in Europe. American tourists flashed rolls of cash, booked the best hotels and dined in four-star restaurants. His life at home and in the military was less than what he was seeing.

“I knew right then I wanted money, but I knew also the only way I was going to get it was to earn it,” Pena said, nodding absently toward a poster on the wall that says “Poverty Sucks.”

“My parents didn’t have much money and their parents were even poorer. I wanted none of that.”

Pena earned his bachelor’s degree in business administration at California State University, Northridge, jammed his days full of graduate courses thereafter and finally took a job with a real estate investment company in 1971. The tempo of success began there.

Before the year was out, he had been appointed sales manager of the company with a six-figure salary and had cleaned out the department by firing 50 salesmen—a job, he observes without significant remorse, that had to be done. It earned him the name Hatchet Man.

“I ran my staff like an infantry platoon,” Pena said. “I slept in the office, afraid that every hour I wasn’t there I wasn’t making money . . . .”

When the company failed, Pena went into shock. “My first taste of success had exploded in my face. Now I needed success more than ever.”

Wall Street seemed closest to where the cash lay, so Pena became a stockbroker and then a financial planner, moving up literally and figuratively from Volkswagen to Rolls-Royce in a fleeting few months.

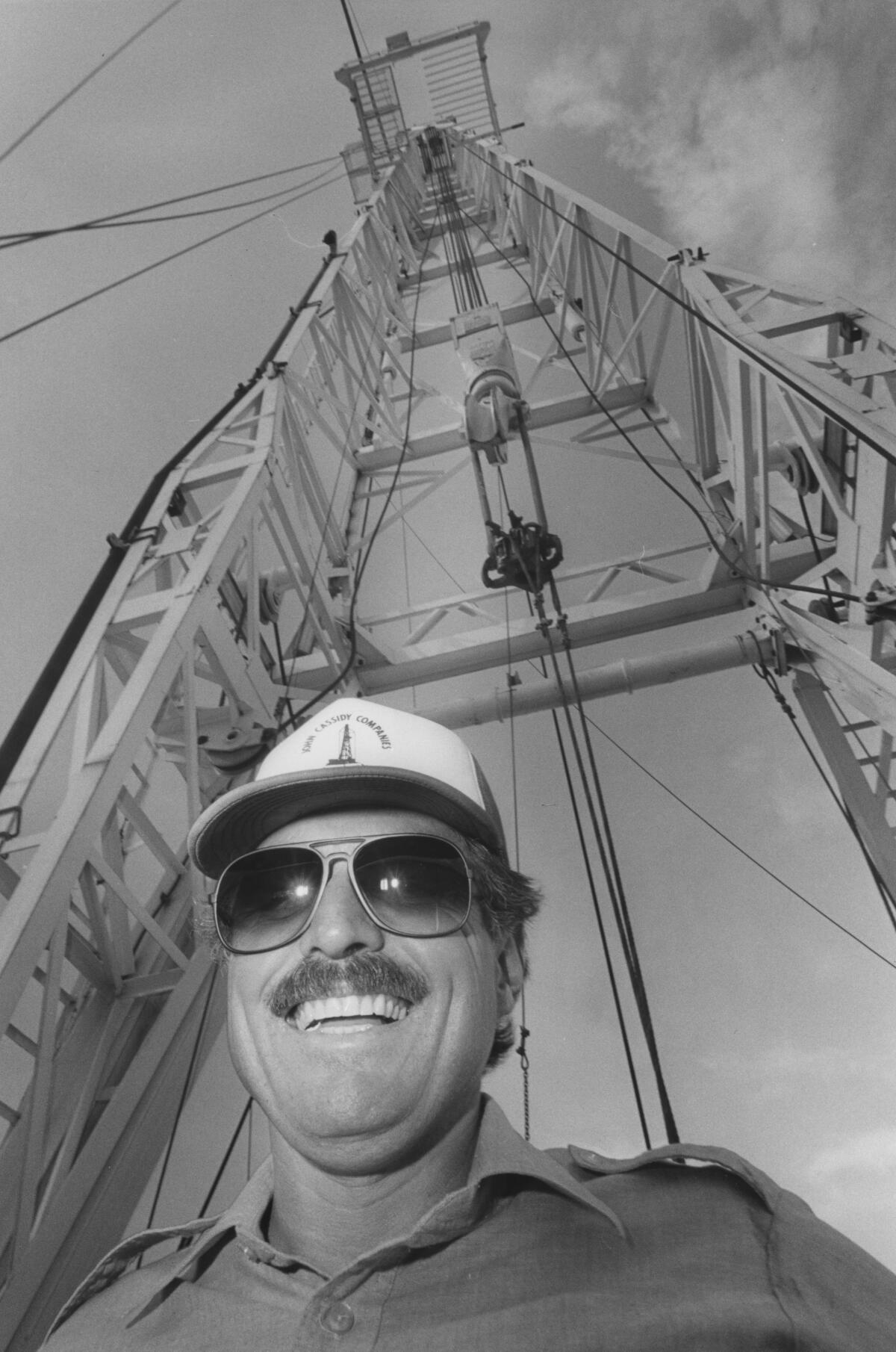

He began looking at oil investments when a friend became suddenly rich on a rocket of soaring petroleum prices. Within months—reading everything he could find, working 16-hour days, driving himself “like a wild-eyed madman”—Pena was chairman of the board of an independent oil company and chief operating officer of its administrative arm.

Within three years, he had his own companies, Great Western Development and Great Western Energy, and was going full tilt as an oil broker and well-driller. Today, he applies that same wild energy toward buying his own refinery and petroleum dock.

“I’m not the way I used to be,” Pena said, putting another stick of gum in his mouth, squeezing the hand grip, tapping his foot nervously. His $300 boots are made of alligator skin. “I’ve learned patience. I’m not running as hard.”

That doesn’t mean he’s soft, he adds quickly. That doesn’t mean he had the “peon mentality” that assumes the world owes him a living. No one owes Dan Pena anything.

“Maybe we owe the blacks because the blacks were slaves,” he said. “Mexicans aren’t slaves and never have been. I believe in a note my dad wrote me when I was 12.”

He opened the note and read: “The future is yours. Have faith in yourself.”

“There are very few success-level 10’s in the world,” Dan Pena said without the least hint of modesty. “But I’m one of them.”

Having established that identity, he sat quietly for a rare and passing moment, reflecting on his own image. The television stock market commentator played quotations pianissimo in the background.

::

Manuel Caldera, overweight and unassuming, edged into the small, exclusive dining room of Palm Springs’ Ingleside Inn as though he expected to be almost instantly ordered out. He hesitated, scratched, looked around and waited for whatever fate, no doubt unpleasant, that might await him. Demons lurked in the soft, candle-lit shadows. Caldera seemed certain that they would possess him.

Then the maître d’, bustling about at the behest of more glamorous patrons, spotted Caldera loitering uneasily in the entryway. He flew to his assistance like a servant to a king, ushering him in with the kind of low, sweeping gesture reserved for celebrities in a city fat with them. The best table. The best wine. Nothing was too good. Manny was in town.

It wasn’t just Caldera’s money they were servicing, nor the charming manner of his diffidence. He is a man admired for a multiplicity of reasons, not the least of which are cash and affability, but not the most of which are either.

Caldera is respected because he bobbed up off the streets with a buoyancy that never turned mean, and in his rise to ownership of 700-employee Amex Systems, he has managed to maintain a pride in two cultures that never seem in conflict.

“I’m one of the lucky ones,” he said, sipping a martini at the Ingleside. “I’m an American and a Mexican. I’m rich and honorable. Who could ask for anything more?”

Then he settled down to a prime rib dinner on a cognac-colored night with the self-assurance of a man who, shyness notwithstanding, knew exactly who he is . . . .

Morning. The scent of orange blossoms perfumed the dry air of Palm Desert. Caldera was up at 6 after a night of partying. He was playing tennis next door, tanned, balding and slightly paunched, moving on the court with the bounce of a younger man. A portable telephone, the long reach of ambitious executives, was propped up near the fence.

Often he rises at 4 a.m. to call Washington because most of his high-tech sales are made to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the Defense Department. That night he was to fly to the capital, aware that in the end a disembodied voice isn’t enough. It’s his presence that has thrust Amex into space communications, avionics and weapons systems. Being there is everything.

“My goal,” he said, relaxing after tennis, “is to turn Amex into a $400-million-a-year-company, and that won’t be done without a certain dedication to priorities. That doesn’t mean I’m a workaholic. I’m not. Priorities include enjoying life. I take time to smell the blossoms. . . .”

Caldera was sitting on the back deck of his Spanish-modern home, near the swimming pool. He lives alone on the edge of the desert when he isn’t on the move or with is girlfriend in Los Angeles. He has been divorced for 11 years and has three grown children, one of them an institutionalized mentally retarded son.

“You know what gave me the first break?” he asked. An emerald ring gleamed in the sunlight. “three grades of going to a ‘superior school.’ During the Second World War, we lived in the home of a Japanese family interned in a camp. I went to a non-barrio school for the second, third and fourth grades.

“When we moved back to the barrio, I was so far ahead of the other kids that I skipped a grade. I could have skipped two or three. The schools for ‘other people’ were better than our own. Forty-one years later, they still are.”

Caldera was born in San Pedro, the sone of parents who had migrated from Mexico. After three years at “a better school,” he continued his education, but only to the ninth grade —“If you were Mexican-American, they had you taking five hours of shop a day because they figured that was the best future you’d be offered. I couldn’t buy that, so I quit.”

At 15, he joined the Army, didn’t like it, revealed his true age and was thrown out. Then he studied aviation mechanics, passed a high-school equivalency test, attended college for two years and looked “for a professional Mexican-American I could ask for a job, a Chicano who wore a tie to work. But there were none . . . .”

Again he went into the Army, this time via the draft, and to Officers Candidate School, where his life changed.

“Up until then,” Caldera said, “I really, truly believed I was inferior, that all of us were laborers. The suddenly, in officers school, I ended up as only one of nine students to graduate from engineering out of a class of 45. At last, I could stop looking over my shoulder.”

After the Army, he went to work for aerospace companies in engineering and marketing, bought into an electronics business that failed in six months and, in 1971, created Amex with $17,000 he had saved.

Today he owns Amex, his $300,000 Palm Desert home, a condo overlooking the Potomac and property in San Diego where he plans to build his dream house. He put two daughters through Georgetown University, drives a new Cadillac, dines well, parties when he feels like it and travels the world for recreation.

But that isn’t all. “I’m proud of my heritage,” Caldera said, “and felt I had to give something back.”

He joined the board of the Mexican-American Foundation, the Latin American Manufacturers Assn. and other minority-flavored organizations.

“Just like in caveman days, the guy with the biggest club still wins it all,” he said, taking a phone call on the patio. It was the State Department, inviting him to a conference on foreign affairs later in the month. He accepted, hung up and turned with a smile. “Only the clubs have changed,” he added softly.

::

When cinematographer John Alonzo first moved into his $1.6-million Brentwood home, a woman who lived down the block wanted to hire him. As a gardener.

“I was working in the front yard when she came by and began asking questions in English,” he said between holes at the Mountain Gate Country Club in the hills above the San Diego Freeway. A light rain was falling over the Sepulveda Pass, and the golf course glowed emerald green.

“Just for the hell of it, I pretended I didn’t speak English. ‘No hablo Ingles, senora.’ She said, ‘Is the, uh, el dueno of the house in?’ trying to figure out how to ask for the owner. I smiled and said, ‘Ah, si, el dueno’ and stared at her, smiling. She finally sighed and said, ‘Forget it, I’ll talk to you some other time.’

“About half an hour later, she saw me drive off in my Mercedes and must have realized right away that I was el dueno. We’ve become friends since then and, you know, she’s never brought the incident up?”

The story was told with a good-natured forgiveness of the silly Anglo woman who presumed that anyone who looked Mexican and who was working in the garden of an expensive Brentwood house just had to be a gardener.

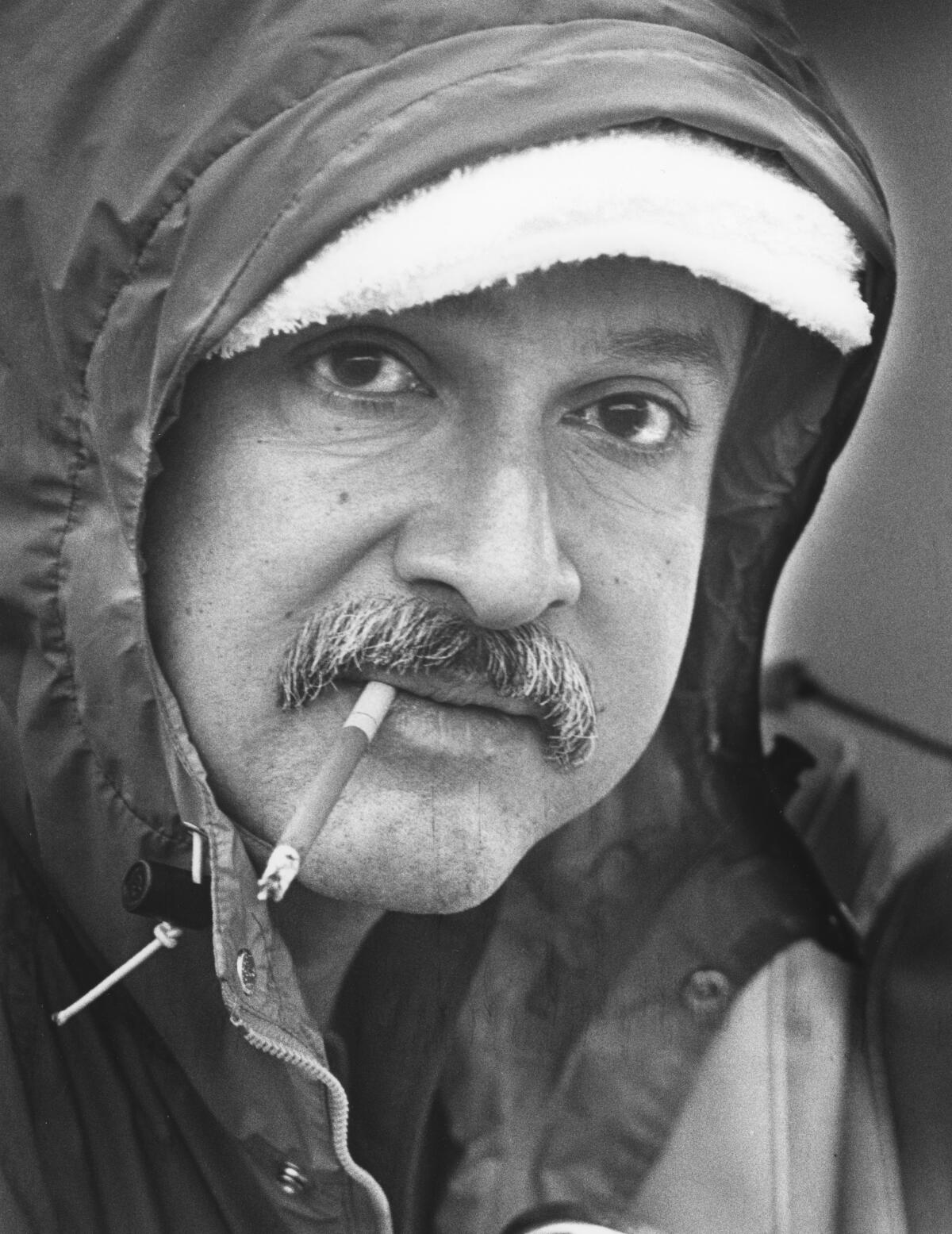

By now she knows that her dark-skinned neighbor with the graying hair and mustache, a man of slight stature who smokes cigarette-sized cigars with the same intensity he brings to movie-making, is one of Hollywood’s finest cinematographers.

Her mistake was, in some ways, understandable. Alonzo not only looks Mexican—his father is a Mexican Indian—but also emits a kind of cultural aura by his dedication to la raza. He’s proud of who he is and always has been, scornful of those who, in his Texas childhood, masked their roots by denying their heritage.

“I was never Spanish,” Alonzo can say wryly, understanding the nature of his individualism. “I eat Mexican food, I listen to Mexican music and I buy Mexican art. I am also paid more than $10,000 a week and am offered more movies than I can possibly accept.”

Nominated once for an Oscar (“Chinatown” — he didn’t win it), Alonzo has gathered honors from around the world for his cinematography. In one year, three of the films he worked on — “Sounder,” “Pete and Tillie” and “Lady Sings the Blues” — won Academy Awards.

“I’ve got an Anglo to thank for all this, I guess,” he said between golf shots, standing in the soft drizzle, waiting for his wife, Jan, to putt. They have been married 23 years. She is a redhead, half-Irish and half-Indian.

“I was just out of high school. Jay Watson, who managed a television in Dallas, had promised to hire me when I graduated. I started out by sweeping floors and pretty soon was learning cameras. They fascinated me. It was because of Jay (that) I’m a cinematographer.”

That was in 1953. Four years ago, while shooting the movie “Tom Horn” in Tucson, Alonzo ran into Watson again. His former boss had retired to Arizona and had become aware of Alonzo’s presence in town through a newspaper story.

“We got together,” Alonzo said, “and he showed me a letter he had kept for almost 30 years. It was written by the owner of the station in Dallas. It ordered Watson not to hire any Mexicans . . . at the time Jay was wanting to hire me. Prejudice pissed him off, so he defied the order and hired me anyhow. Jay kept his job, but nonetheless had risked his own career on my behalf.”

Alonzo came to Los Angeles in 1956, worked where he could and decided, with an actor friend’s help, that he wanted to shoot a movie. He called it “Patterns for Murder.” The black-and-white film was completed in 1961 but never released as a feature. They sold it to television seven years later.

While Alonzo dismisses “Patterns” with a laugh (“The best thing about it was the star’s big boobs”), he acknowledges that the film accomplished its purpose. That same year, Alonzo became the first Mexican-American directory of photography in Local 659 of the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees. Within a decade, he was invited to join the prestigious American Society of Cinematographers.

Today, Alonzo and his wife count their holdings — real estate, part of a shopping center, interest in a bank — in the millions. He admits, however, that despite his money and standing, he continues to face instances of bigotry.

“It began in the first grade of an English-speaking school in Texas when a teacher slapped me for speaking Spanish,” he said. The rain began falling heavier over Mountain Gate, sending other golfers scurrying for cover. Alonzo ignored the storm, practice-swinging a driver in gentle arcs, pausing finally to consider his memories.

“And it happened again not too long ago. We were shooting a movie in Ocala, Fla., and they put us up in country club cottages right on a golf course. I try working in some golf wherever I travel. But not in Ocala. They refused to let me use the course because I’m Mexican. The irony is that the pro at the club was Jose Lopez. A Mexican.

“I didn’t fight it. The owner of a local furniture company became incensed and arranged it so I could play at any other club in the area. Maybe they learned something in Ocala.”

Alonzo’s wife is less forgiving. “He’s been dragged face-down over seven miles of bad road to get where he is,” she said angrily. “But he’s done it.”

Alonzo leaned over the ball on the seventh hole, ready to tee off. “I won’t bow to racism,” he said, “I never have. I never will.

“But I do try to keep it in proper perspective. There’s a reality we should all deal with.” Alonzo smiled. “The Anglos are a minority in Mexico.”

He swung, and the ball sailed off, high and far. Alonzo watched it, a tiny, disappearing dot against the rainy sky, until it was only an imprint on his memory, and then it was gone.

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.