Latinos find job choices are both limited and limiting

Gladys M. loads her two young daughters into her spinach-green 1975 Dodge Coronet, leaves her East Los Angeles apartment and heads for the monied side of town. This day will be like all the others for the 29-year-old Salvadoran, who is afraid to have her full name published—she will scrub another woman’s floors, wash her clothes, even feed her fish.

A few miles away, Raul Palacios waits for the bus that will take him from his Highland Park home to the Stock Exchange Club in downtown Los Angeles, where he will stand over a sizzling grill, watching rows of steaks turn deep brown and listening to impatient waiters clamor for their orders to be filled.

Jerry Espinoza doesn’t know what he will do on this morning; time has moved slowly ever since he lost his job last year when Bethlehem Steel Corp. closed its Vernon factory. Espinoza may go to the unemployment office, or maybe he will go on a job interview. But for a 45-year-old steelworker with a bad back and hearing problems earned on the job, he knows there are few opportunities.

Guillermo Alvarez, who was once advised by a high school counselor to become a mechanic like his late father, brushes off his blue three-piece suit and straightens his tie. A hard-won business administration degree has meant sacrifice and change for the 27 -year-old savings-and-loan auditor. He has found success in the white-collar world, but has learned that Latinos who try to crash the gates of corporate America will find a foreign culture full of obstacles not always encountered by their Anglo counterparts.

When I go looking for a job, no one is hiring. Or maybe they are hiring but they look at me and maybe l’m too old or maybe it’s my nationality, because they still discriminate.

— Jerry Espinoza

Gladys M., Palacios, Espinoza and Alvarez are on different rungs of the Latino labor-force ladder. While the lot of working Latinos has improved during the last 20 years, the fact remains that Latinos have trouble finding jobs and receiving a decent day’s wages for their work.

There are still tales of job discrimination and insensitive bosses. And yet thousands of immigrants are willing to illegally enter this country for work. The thread that ties them all together is hard labor: Latinos are vigorously working to buy their piece of el sueño Americano, the American dream.

That dream is hard to come by:

- The average working Latino is more likely to hold a blue-collar job (44.8%, in 1981) than is his Anglo or black counterpart. And although statistics suggest that there are more Latino professionals and managers than ever before, many of those who hold white-collar jobs-particularly women-are clustered in low-paying clerical positions.

- A total of 16.5% of. U.S. Latinos are service workers-holding jobs such as janitors, cooks, dental assistants and fire fighters. While the bulk of farm workers are Latinos, only 3.87% of U.S. Latinos are farm workers, a figure that counters the popular misconception that most Latinos work in the fields.

- Latinos are well represented in the ranks of the unemployed, with an annual jobless rate of 13.8% in 1982, well above the Anglo unemployment rate of 8.6% but lower than the 18.9% rate for blacks. Moreover, almost 30% of all Latinos had income in 1982 that fell below the national poverty level, according to statistics from the Census Bureau.

- Latinos have a strong willingness to work — and to work hard, a recent Los Angeles Times Poll found. Directed by I.A. Lewis, the poll discovered that the Latinos surveyed had a stronger identification with the so-called Protestant work ethic than any other group. When asked what they thought is most important in life, 48% of Latinos said working hard, rather than personal satisfaction.

- Despite faith that hard work will provide a better life, in the past 12 months, more Latinos than blacks or Anglos had unfavorable salary developments such as being fired, being laid off, or having work hours or overtime cut, the Times Poll also found.

- Latinos’ difficulties in the labor force are traced to problems with English proficiency, low levels of formal education (exacerbated by English problems) and discrimination. A recent study by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that when everything is equalized — education and age, for example — and no matter what the economic climate, minorities and women still come out on the short end of the employment stick. “The suspicion, therefore, remains that discrimination continues to have a major effect on blacks, Hispanics and women in their struggle to find jobs commensurate with their qualifications and experience,” the report stated.

Labor statistics and pessimistic pronouncements, however, don’t begin to tell the stories of the working lives of today’s Latinos, people who work hard in jobs they may not like for wages they wish were higher.

::

It is a hot summer’s day in Los Angeles, and the two girls splash in the pool behind a sprawling house in Studio City. Inside, their mother, Gladys, is cleaning house, just as she does every weekday at five different homes across Los Angeles.

Hers is a story of determination to achieve more for her three children than she has had, a drive not lessened by the fact that her husband holds a low-paying but steady white-collar job in a bank, while also going to school.

This day Gladys will make $40 for six or eight hours of work; some days she earns a little more, most days she gets a little less. Sometimes Janet, 10, lends a hand while Cindy, 6, plays. Other times the children stay home.

There is no task around the house that Gladys doesn’t do. A husky, strong woman, she thinks nothing of moving a heavy couch when she vacuums or pulling out a giant double-door refrigerator to sweep. Her least favorite job is cleaning ovens.

A house never takes more than eight hours to clean, and if she pushes it, Gladys says she can finish in four. Because she cleans some houses more than once a week, she will often do two homes in one day. Sometimes, after a day of cleaning house, Gladys will work in the kitchen while her employer entertains.

“I think the life is a little bit hard,” Gladys says, constructing her English sentences in Spanish syntax. “The only thing I know is to work and work and work. I never rest.

“Sometimes I wish I could stay home, especially when my house isn’t clean,” she adds. “Whatever I have to do, I do-and I enjoy it.”

But Gladys doesn’t enjoy house keeping enough to want her daughters to do it.

“I don’t want this for them,” she says, shaking her head firmly.

“I want something better for them, but I let them choose whatever they want to be.”

Gladys would like all her children to attend college, particularly 14-year-old Carlos, who earns consistently high grades in school and “would like to work with computer machines.”

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

House cleaning, like farm, restaurant and garment-industry work, is the sort of entry-level position that new immigrants find themselves forced to take. Many of these people are undocumented, unable to speak English and, therefore, ripe for employer exploitation. Moreover, these workers are not entitled to the protection of federal labor laws providing for unemployment compensation, collective bargaining or protection under some state workers’compensation laws.

Gladys, who has been a housekeeper ever since she came to the United States 12 years ago, is in some respects better off than many of the Latinas who do this kind of work because she is able to reject employers she doesn’t like. (Although she says she lives in this country legally, Gladys prefers to be paid in cash and doesn’t want her last name published in the newspaper.)

After five days of cleaning other people’s homes, Saturdays find Gladys putting her year-old beautician’s license-bought with two years of night school-to use in a West Los Angeles salon. “I would like to be a beautician all the time, but in my own beauty shop,” she says.

“I think I will — I have hope,” she continued. “I don’t know how long it’s going to take, but some day. I’m trying to save something for it. That’s why I’m working very hard now.”

::

Raul Palacios remembers harvesting crops when he was only 5 or 6 years old and later, toiling on a ranch in the mountains of Chihuahua that his family built on land given by the Mexican government.

“I was a Mexican cowboy,” he says, laughing, because the romanticized cowboy image is so different from the existence he knew. But “when I was 18, I was tired. I worked so much and we were so poor and I decided to come (to the United States).”

Palacios and his wife, Pauline, live in the modest but comfortable home in northeast Los Angeles where they raised three children. The youngest is well on her way to becoming the first of their family to graduate from a university.

While the Palacioses admit they dislike the drudgery of their work, they credit the low pay for the life they now enjoy, because it forced them to work harder.

“Raul and I, we got to where we are because our jobs didn’t pay well. We had to economize,” says Mrs. Palacios, who recently was laid off from her $4-an-hour job as a “floor girl” for a downtown Los Angeles non-union, garment manufacturer. “All we needed was the money coming in, so we stayed in our jobs.”

Palacios spends his mornings trimming cuts of meat and making hamburger for the Stock Exchange Club kitchen. During the lunchtime rush he mans the restaurant’s grill.

Eight hours (at work) isn’t so bad. Nowadays we’re all spoled. We complain, but we come home and watch TV, and it’s easier.

— Raul Palacios

“To be a cook is kind of an art, just like a musician,” he says. “I don’t care how much you study, you cannot do it if you don’t have the art.”

But the kitchen, with its heat and bustle, is not an artful place. In fact, Palacios calls kitchen work “the worst job there is.”

“You’re standing over the stove and the waiters are on top of you,” he says. “All the waiters come at the same time with different orders. One wants a steak well done, one blood rare.

“Boy, it’s hard. And if the customers don’t like it, they send it back,” he continues. “By the time you leave, you’re nuts.” At the end of the day Palacios is so tired of being around food that he seldom touches the dinner his wife has prepared.

Before she lost her job a few weeks ago because of a slowdown in orders, Pauline Palacios had a variety of daily duties including trimming and bundling clothing, and helping with shipping. Mrs. Palacios is looking for a job outside the garment industry, where wages have been dropping during recent years because new waves of Central American and Asian immigrants desperate for work are undercutting pay scales.

“Right now the sewing industry’s for the birds. They don’t pay you anything,” she says. In the past, garment industry jobs “didn’t pay great, but you could live on it. But now it’s so low it’s disgusting.”

But the 58-year-old Palacios frowns and shrugs, recalling his life in Mexico when he worked long days, sometimes barefoot in the snow.

“Right now we’re complaining’ he says. “Eight hours (at work) isn’t so bad. Nowadays we’re all spoiled. We complain, but we come home and watch TV, and it’s easier.”

::

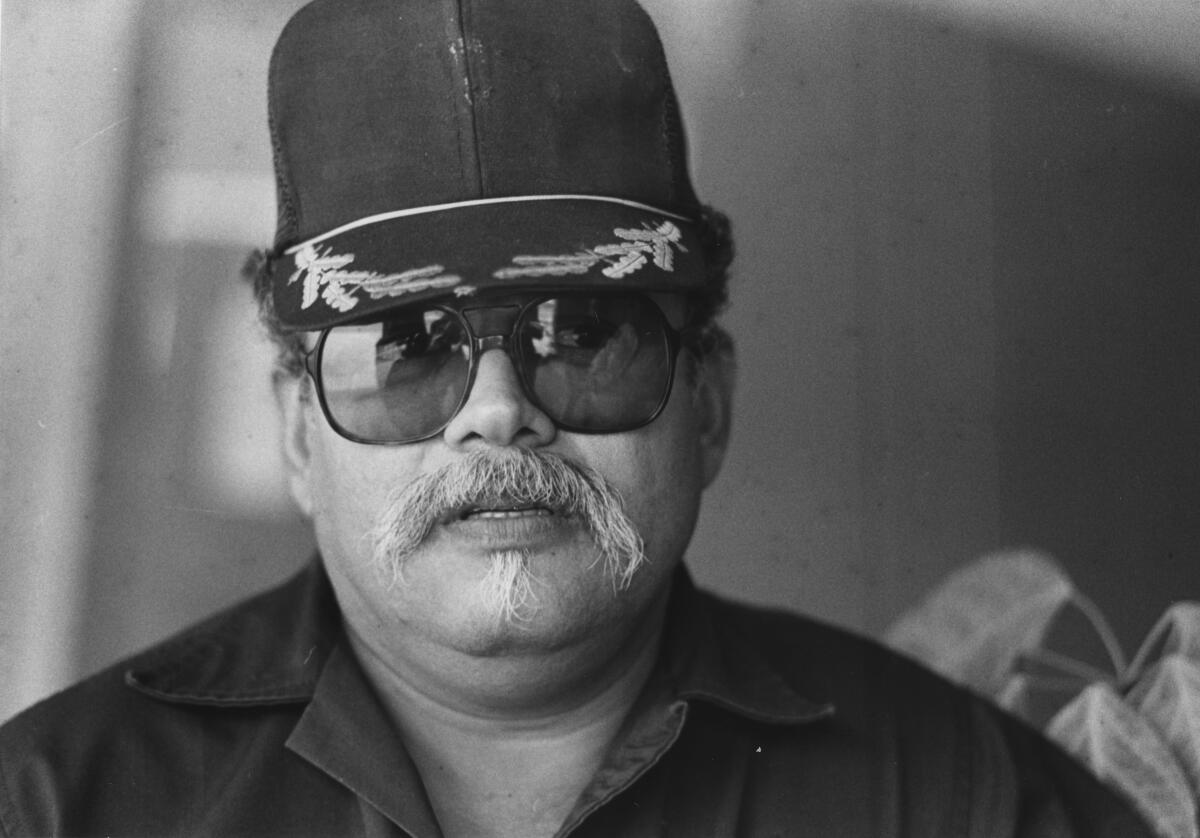

“I’m looking for a job right now, trying to regroup myself,” sighs Jerry Espinoza, who lost his job late last year when Bethlehem Steel closed its factory in Vernon.

Espinoza has five children, mortgage payments and a few hundred dollars coming in each week from unemployment insurance and supplemental benefits paid by Bethlehem Steel. He says that his wife’s paycheck is all that keeps the family going.

Stories like Espinoza’s could become more common in the future as the economy shifts toward computers and automation. Blue-collar jobs-more often held by minorities-will begin to evaporate, and the jobs that will be created in white-collar categories are often the types of positions that Latinos and other minorities have difficulty acquiring.

“When I go looking for a job, no one is hiring. Or maybe they are hiring but they look at me and maybe I’m too old or maybe it’s my nationality, because they still discriminate,” Espinoza, 46, says.

Espinoza gave 23 1/2 years to Bethlehem Steel, “and it took the best part of my life, physically.”

He says that he has hearing problems because he ran machines in the plant’s industrial fasteners department for several years without ear protection.

After that department was shut down, he worked as a laborer wherever he was needed in the factory. His left hand is scarred and two fingers are numb from a job-related accident. Then, shortly before Bethlehem announced the plant closure, he hurt his back. That injury still bothers him.

Company-sponsored retraining programs-mainly classes in computer programming or preparing resumes-are impractical for older workers who have been out of school for several years, he says. “It’s like trying to learn how to walk again.

“Why don’t they set up a class for brain surgeons, too?” Espinoza adds sarcastically. “I’m looking for a retraining program like welding, something I know I can do.”

The unemployment line demands a heavy payment, the steelworker says as he sits in the union hall of local 1845, within sight of the idled Vernon factory.

“One day you’re OK, the next day you’re depressed,” he continues. “We’re just lost souls now; that’s what we are, lost souls, because of our age...and injuries that are going to work against you in the job market.”

Selwyn Enzer of the University of Southern California’s Center for Futures Research says that Los Angeles County’s fast-growing Latino population is a blue-collar work force that isn’t suited for the predominantly white-collar jobs that will be available in the year 2001. This means unemployment will be a critical problem for Los Angeles in the future, or that the Latino population growth will slow sharply because these two trends probably can’t coexist.

“We don’t have to look at these blue-collar workers as a liability, we can look at them as an asset,” Enzer, the research center’s associate director, says. “We have to create an environment where we can put these people to work.”

::

Guillermo Alvarez is typical of the young, educated Chicano who has hoisted himself out of the barrio and into corporate America. He drives a sporty car from his home in Montebello to his job as a savings and loan auditor in Costa Mesa.

But his and other success stories weren’t written without some pain. Many Latinos say they and other minorities often must carry a knapsack of extra burdens up the corporate ladder in addition to learning the unfamiliar idiosyncrasies of corporate life.

“I like what I do,” says Alvarez, whose work is far removed from some earlier jobs picking fruit, delivering newspapers and flipping hamburgers. “I like being able to show what I can do.

“The business environment is being enhanced by having individuals with nonwhite points of view,” he continues. “They (corporations) are finally opening their eyes and tapping the Latino market, and they see that there’s a lot of potential out there.

“We do have our foot in the door. Whatever key it was that opened the door—it doesn’t matter,” he says. “We’re here now and we just need to go on from here and prove ourselves.”

His entry into the corporate life, however, was less than smooth; it was a time of cultural adjustment—something he wasn’t taught in the classrooms of California State University, Los Angeles. Alvarez got his initiation at the accounting firm of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co., but he believes similar stories can be found at any large corporation.

“The first week at Peat, Marwick, Mitchell they put you through this orientation and they teach you the Peat Marwick way,” everything from the accounting firm’s audit practices to what employees should wear and where they should eat lunch, Alvarez remembers.

Bringing brown-bag lunches and eating in fast-food restaurants were discouraged, he adds. Alvarez had to borrow money from one of his brothers to transform his Levi-dominated closet into the “dress-for-success,” three-piece suit wardrobe his new employers suggested.

But lunch and dress regulations were only superficial rules in the world of corporate gamesmanship.

“I think the real cultural shock basically was the differences in the egos that are involved. You see people who are very driven, very competitive,” Alvarez says. “I’m sure there are a lot of Latinos who are competitive, and I’m competitive in certain situations, but I didn’t have the background to handle the (corporate) competition. . . . My background was to respect my elders and stuff like that, and you take that into the business world and it doesn’t work.”

This cultural difference experienced by Alvarez and others can be traced to childhood when Latino children are taught to obey — with rules such as don’t argue with your father or your teacher or your boss — while Anglo children are taught to question and to assert themselves.

Among Latinos, who tend to stall in low-level positions, it is typical to work hard in a corporation while quietly waiting to be promoted, according to J. Manuel Casas and Gladys DeNecochea, partners in IMC & Associates, a small Santa Barbara-based consulting firm that deals with the problems of Latinos in corporations. That attitude isn’t good enough, they say.

“You’re going to have to learn how to play games, corporate games,” says Casas, who has worked with more than 500 Latino managers, mainly in Southern California. “Don’t expect to be noticed, you have to make yourself noticeable.”

Because Latinos are underrepresented in upper management, lower-level Latino employees find there is no corporate network to support them and no Latino mentors or role models to guide and advise them-resources considered valuable in rising to corporate heights, Casas adds.

Among the Latinos who have made it in corporate America, becoming a mentor to young Latinos like Alvarez is a priority. Take Leo Trujillo, the 48-year-old division material and subcontracts manager for TRW Inc.’s Torrance Software & Information Systems Division.

“I’m developing a group of Hispanic managers, a group of Hispanic professionals,” Trujillo says. “I’m pushing these people, telling them, ‘Get a master’s (degree). If you want my job, get a master’s.’”

Improving the lot of Latinos is crucial, because only if Latinos gain positions of power in corporations will they be able to affect tomorrow’s issues, he says.

Latinos burn out in corporations because of the extra demands put on them that non-minority co-workers don’t face, says Casas. For instance, Latinos often are expected to be experts on Latino customs or “the Latino market” in addition to performing the duties of the job for which they were hired. The Latino community, searching for role models, places still more demands on the managers’ time and energies by requesting their Presence at a multitude of community activities.

“The Hispanic manager is like the chicken in the chicken coop. Everyone is plucking him and pretty soon he’s lost all his feathers,” says Trujillo. “It’s not so bad, but you burn out.”

Many white-collar Latinos may find themselves stereotyped, allowed to work only with Latino customers or placed in offices in Latino neighborhoods, Casas says. What’s more, Latinos face some condescension from co-workers who view them as a product of affirmative action.

“Especially in these economic times when a lot of people are out of work, if you’re hired as a minority or a woman where the majority are white and male . . . people are going to say, ‘Why was this person hired?’

“Then you start questioning yourself and now you have an additional burden as you try to move ahead in the corporation,” Casas adds.

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.