Chicano Movement: Generation in search of its legacy

Like calaveras bailando — the humorous, dancing skeletons of Mexican folklore that teach us to celebrate life by laughing at death — the partygoers laughed and danced, recalling for an evening the lost intensity of their tumultuous youth.

It was a reunion of sorts for the Chicano Movement.

A decade had passed since the death of the movement. In the interim, most of the young Chicano “revolutionaries” had joined the establishment as lawyers, business executives, college professors or bureaucrats. But they were still bound together by the political rite of passage that had forged their generation’s Chicano identity.

As young people around the world rebelled in the 1960s against the established order, Chicanos in the Southwest searched their roots and bristled at the inequity characterizing their people’s experience in the United States. In an explosion of youthful idealism, they set out to rebuild Aztlan, the mythical Aztec homeland that became a symbol of self-determination, of a Chicano Southwest.

Now, at an East Los Angeles restaurant, the 1960s beat of Santana enveloping the room, members of la generación de Aztlan gathered to rally around an old star.

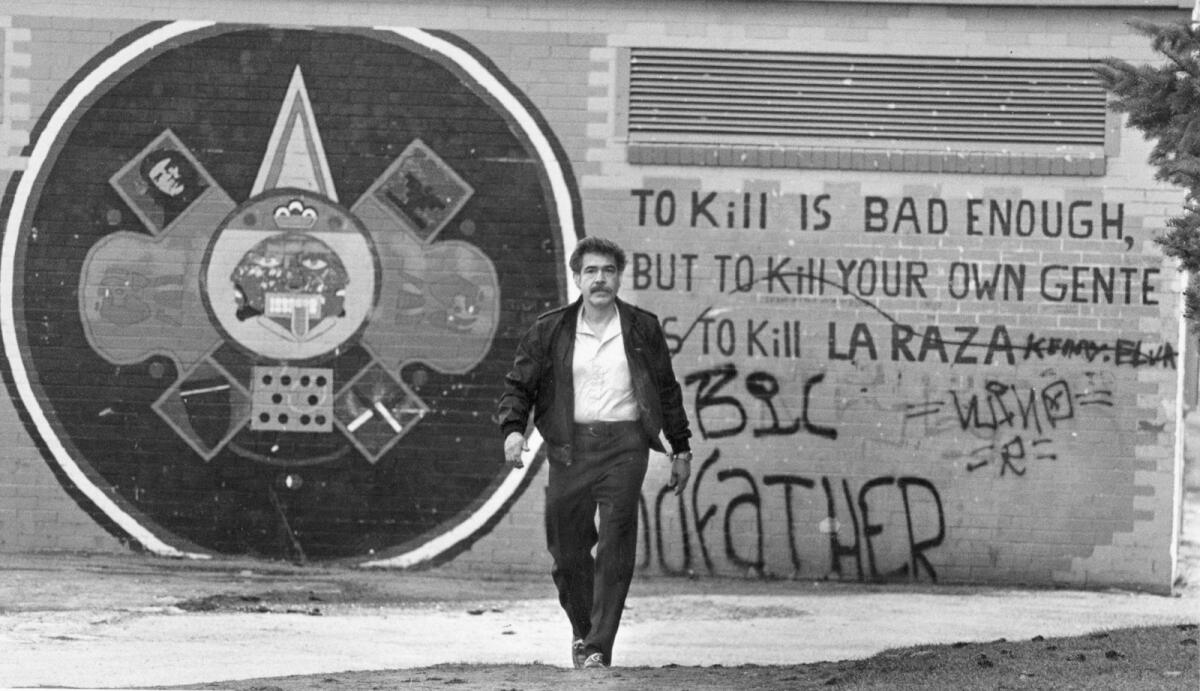

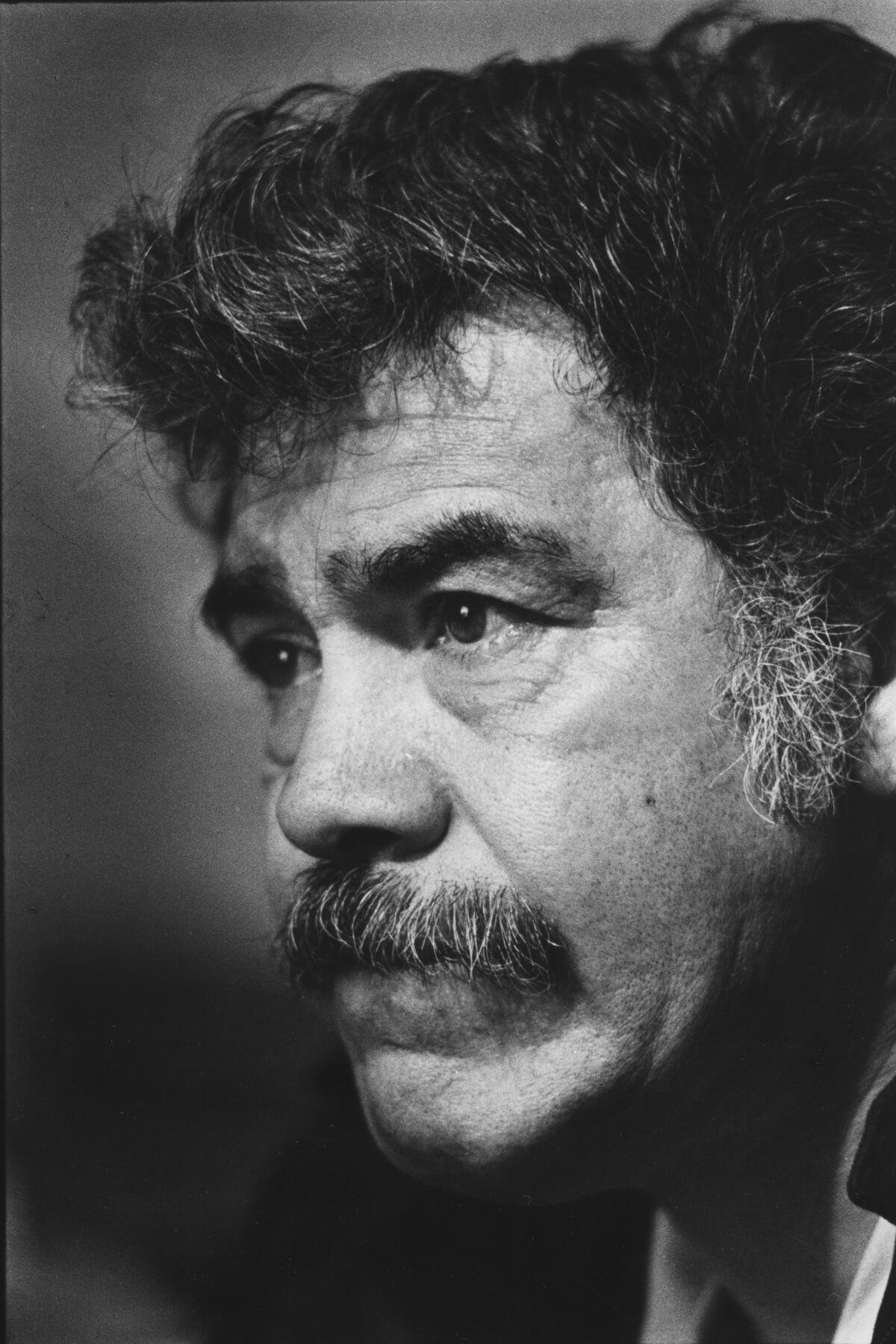

Raul Ruiz, leader in the now-defunct La Raza Unida party and former target of FBI surveillance, was returning to the public fray as a candidate in the April primary election for the Los Angeles school board. Ruiz, now a Chicano studies professor, had been among those in the movement protesting the loudest against the school system’s treatment of Latino students.

The calaveras looked older now. They had lost their innocence in street confrontations with police and in the realization that the system they challenged was stronger than they were.

A few, like the legendary Oscar Z. Acosta, whom they called the ‘Brown Buffalo” and the “movement’s lawyer,” were reportedly dead. Others were said to have dropped out or sold out. And some of the former girlfriends and wives of the movement’s youthful leaders had come to the Ruiz fundraiser alone. Many had not seen so many familiar old faces since Ruiz’s 1971 unsuccessful run for the state Assembly.

Ruiz would lose the school board election. But the night’s reunion would remain significant for those who were there.

It raised a question each had wrestled with in different ways: Though the dream of Aztlan had faded, would its legacy be strong enough to sustain a generation’s commitment to change?

::

In the midst of the black civil rights movement and antiwar protest, a new generation of Mexican-Americans took a hard look at their place in American society and grew angry at what they saw: the lowest per-capita income of any group in the country and one of the highest unemployment rates; half of their youngsters dropping out of high school and few making it to college; virtually no political representation, and young Chicanos dying in Vietnam at nearly twice the rate of others.

Underlying it all, they discerned a lack of respect for their culture and little concern for their condition.

The so-called “silent majority” had suffered in silence long enough.

“It was like someone threw cold water on our faces. We woke up and ... said, ‘No more,’” recalled Richard Martinez, a college student at the time who later ran Ruiz’s Assembly campaign. “We were on the radical edge of insanity. We had clarity of vision that polarized the world between good and bad.”

Rooted in the same deep-seated discontent that moved earlier generations of Mexican-Americans to protest their economic and social condition, this movement’s focus was on civil rights, educational opportunities, opposition to the war and ethnic identity.

It was a movement of young people who rejected the term Mexican-American as something imposed on them, and called themselves Chicanos. A growing sense of community and common purpose evolved into a nationalistic ideology. If the established institutions refused to open their doors to Chicanos, then Chicanos would build their own schools, publishing houses, political parties and health facilities.

“We were young and naive and we really believed we were going to create a healthy Chicano California, one big happy family. It was Aztlan, and we were really going to run with it,” recalled Richard Cruz, a Loyola University law student at the time.

Breaking with their elders’ accommodative approach, young people in barrios across the Southwest took to the streets. In East Los Angeles, thousands of high school students staged walkouts, and others demonstrated against the war.

But some frowned on this defiance by the young. It was not unusual for an angry parent to show up at a park rally and pluck a youngster from the crowd.

Cruz estimates that during the height of the period, which spanned the late 1960s and early 1970s, as many as 150,000 Mexican-Americans participated in mass demonstrations and rallies in Los Angeles alone.

“We did everything but take up arms against the establishment,” he said. “At the 1970 Moratorium (antiwar demonstration), you saw 20,000 to 30,000 fighting faces. It was a fight. Nobody misunderstood.”

When law enforcement officers arrived at the East Los Angeles demonstration, a violent confrontation erupted and mass arrests followed. Hundreds were injured and three men were killed by police, including Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar. The journalist was shot in the head with a tear gas projectile when a sheriff’s deputy fired into a bar where Salazar had stopped for a beer.

On the college campuses, student groups adopted the name MECHA, an acronym in Spanish for Chicano Student Movement of Aztlan, and pressed for increased Chicano enrollment and courses about their people’s experience in the United States.

“We were militant and angry,” said Cruz, recalling the demonstrations he helped lead to boost Chicano enrollment in law schools.

College students took inspiration from emerging leaders like Cesar Chavez and his unionization effort on behalf of farmworkers. They invited other notables to their conferences and rallies.

Reies Lopes Tijerina, a fiery ex-evangelist, became a symbol of courage to Chicanos when he led an armed raid on a county courthouse in northern New Mexico. He jostled their memory with his campaign to restore early Spanish and Mexican land grants to the descendants of the original owners, charging that the lands had been illegally seized.

“Reies showed us what it’s like to fight con muchos huevos (with a lot of guts),” recalled a young New Mexican journalist. “He turned the world upside down on us and forced us to look at the issues confronting us as a people.… He turned my generation from Spanish-Americans to Chicanos, he decolonized us and returned us to ourselves.”

Rodolfo (Corky) Gonzales sparked the imagination of young people with his strident talk of “Chicano Power” and his success mobilizing Chicanos in Denver through an organization he called the Crusade for Justice. He also organized “liberation” conferences that brought together young people from across the country.

Jose Angel Gutierrez, a tough-talking young Texan, also gained national prominence after founding a political party called La Raza Unida (the United People). The party’s mission, he once said, was “to paint the White House brown.”

The party, noted for its strong nationalistic tenor, challenged Anglo control of local government in predominantly Mexican-American communities in southern Texas. In 1970, Chicanos took over the Crystal City school board and City Council. The concept spread to other areas, including Los Angeles, although with less success.

In Los Angeles, a group called Catolicos por La Raza (Catholics for the People) pressured the church to use its influence on the community’s behalf.

A confrontation occurred Christmas Eve, 1969, when about 1,000 Chicanos demonstrated in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral, a newly constructed multimillion-dollar church on Wilshire Boulevard. When the protesters tried to enter the church, they were confronted by plain-clothes officers posing as ushers.

“It turned into a tremendous riot, a bloody thing,” said Cruz, who was later arrested along with Ruiz, Martinez and 18 others. Several were jailed.

Cruz, who went on to become an attorney in East Los Angeles, believes the group’s activities helped open the way for the subsequent appointment of Latino bishops in the Southwest; the establishment of the church’s Campaign for Human Development, which funds social programs, and the Los Angeles Archdiocese’s support of Chavez’s union.

Cruz has also seen the number of Chicanos in law schools multiply.

“But we had a lot of growing up to do,” Cruz said. Still, he added, with a smile, “those were tremendous times. Very romantic times. We were all the young Chicano revolutionaries.”

::

The movement’s strength — its youth and spontaneity — was also its weakness. Its idealism was coupled with inexperience, its vitality with a lack of direction.

“We were driven by a hot, passionate anger. It’s what sparked us. People had sat on that anger for years. Once it exploded, we didn’t have the tools to sustain it,” said Martinez, the college student turned campaign manager, with the hindsight acquired after six years as a professional community organizer.

Although Chicanos shared a vision called Aztlan, it was a blurred one. As soon as Chicanos discovered all that they held in common, they also discovered their differences. Competing political ideologies and strategies emerged, and few groups were equipped to resolve them.

While some adhered literally to the concept of Aztlan, others thought that the establishment of separate Chicano institutions was unrealistic. They hoped, instead, to pry open the doors to established institutions.

It was such a debate that spelled the demise of the Raza Unida party. “We never resolved the issue,” said Gutierrez, the founder of the alternative party, who won election to a county judgeship in his Texas hometown.

The party also lacked organizational control.

“Instead of sticking to our initial strategy of taking over one little community at a time … we began running governors in Texas and New Mexico, senators in California. And we stopped organizing,” he said.

And when the Democratic Party perceived the alternative party as a threat, it began recruiting Chicanos to run under the Democratic banner, blunting the effect of Raza Unida candidates, said Gutierrez, now 38 and a teacher at Western Oregon State College. Today, only a few scattered remnants of the party remain.

Compounding these problems was the perception of Chicano activists, along with other protests groups of the period, as threats to the established order. Law enforcement agencies responded accordingly.

Across the country, activism by young people met with stiff reaction. Riots and police brutality marred the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Violent confrontations became commonplace as thousands of demonstrators in cities throughout the United States protested the Vietnam War.

“We found how naive it is to think that because your cause is right and just, that the truth will win out. That’s nonsense. It is a hard-and-fast system that protects its own economic and political interests. And it’s very hard to change it,” said Joe Razo, who was jailed for his involvement in the St. Basil’s riot and indicted with 12 others for his role in the 1968 high school walkouts that became known as “the East L.A. blowouts.” Razo, now 44, is a deputy state labor commissioner in Los Angeles.

It was a lesson that other longtime Latino activists like Bert Corona had learned long ago. Corona, whose experiences date back to the establishment of CIO unions during the late 1930s and early 1940s in California, had seen police battle workers on the picket line and Mexican-American labor organizers labeled “radicals” and deported during the 1950s.

Now his younger counterparts would learn the lesson on their own.

As confrontations with police intensified, the movement’s leaders increasingly found themselves indicted or in jail. Movement organizations were infiltrated by undercover offices and, for a period, East Los Angeles seemed to be under a state of siege.

The Brown Berets, a group of young men in East Los Angeles who donned uniforms and declared themselves “protectors” of their community, attracted the attention of law enforcement agencies.

David Sanches, the leader and self-styled “prime minister” of the group, contends that the group’s paramilitary style was a “psychological ploy to bring attention to the Mexican-American community.” But law enforcement officials took the group’s tough posturing seriously. (Sanchez, a straight-A high school student who served on former Mayor Sam Yorty’s youth advisory council before turning to street organizing, returned to politics last spring in an unsuccessful bid to unseat Councilman Art Snyder.)

Ralph Ramirez, another former member of the group, said he had expected “to be harassed, pulled over, taken in on suspicion of this or that, even to get our heads knocked once in a while.” But he said undercover officers who infiltrated the group tried to provoke violent confrontations with police, and that surprised him.

“That’s when it hit us that these guys were playing for keeps,” said Ramirez, who now works as a job placement consultant with Orange County.

In 1972, shortly before Sanchez officially disbanded the organization (it claimed a membership of 5,000 across the Southwest), about two dozen Brown Berets “occupied” Santa Catalina Island, declaring it “Mexican territory” that had never been ceded by Mexico. They left quietly 24 days later after they were told that they were violating a camping ordinance.

Rudy de Leon, a police lieutenant at the time and the highest-ranking Latino officer in the department, said the Brown Berets were initially perceived as “a lot more dangerous than they actually turned out to be. No doubt about it.” He said he was often called in for consultation on Chicano Movement activities by then-Police Chief Tom Reddin.

“Undercover work was going on all the time” within movement groups, De Leon said, because of the perceived threat. However, De Leon, who left the department five years ago and now works as a special assistant in the state attorney general’s Los Angeles office, denies that officers provoked confrontations.

De Leon, like others still with the department, thinks that the turmoil of the period eventually led to greater efforts by police to improve relations with a community they scarcely knew. But some recall the early police reaction with bitterness.

“There was a general and growing acceptance of the movement in the community. When it started getting massive, local politicians, the police and the media started attacking us,” said Rosalio Munoz, a former UCLA student body president and a leader in the anti-war marches in East Los Angeles.

“The movement didn’t fizzle — it was bludgeoned to death,” said Munoz, who ran unsuccessfully for a seat on the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors twice during the last five years. He now works as a writer for a leftist newspaper in Los Angeles.

“When you see kids shot down on the street, you agonize afterward.… I felt angry, bitter, frustrated for a while. I almost believed it would be best not to demonstrate anymore,” he said, recalling the violence, the court battles and the visits by FBI agents to the homes of movement leaders. “I couldn’t believe how vicious the whole thing got.”

Cruz, the radical-turned-attorney, said that “by 1971, we had the last of the moratoriums, the mass demonstrations and the militant confrontations.… The violence we saw during those years was horrible.… Everybody suffered a lot. Many people are still emotionally disturbed, totally freaked out from the ‘60s …

“By 1973, most of the people I knew ended up getting divorced, or in jail or in (self-imposed) exile. Scores of people began splitting all over the U.S., just to get away, to hide and relax and get their heads together.

“The romance was over,” Cruz said.

::

When Cruz and others look back on the movement, they generally agree that its greatest legacy was the positive self-image it fostered among Mexican-Americans, as well as the sense of community and the increased national visibility it brought them.

“The period, with all its problems with all its pettiness and failures, succeeded much more than any other period in making a greater number of people in the community aware of themselves as a community of common interests,” said Ruiz, who after his unsuccessful school board campaign continues teaching at California State University, Northridge.

Richard Santillan, then a student activist and now a teacher at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, attributed some specific gains to the movement: Farmworkers now have the right to collective bargaining; a state Legislature that had no Mexican-American members in 1967 has seven today; Latinos have won election to Congress with more frequency, and there is a Mexican-American member of the state Supreme Court.

“If anything, the Chicano Movement reinforced our right to exercise our own language and traditions.… We’ve gained greater protection over our rights, we’ve become freer to express our ‘Mexicanness’ and be proud of our culture. Now we can be Hispanic and still move up,” said Santillan, who also works as a Latino political researcher at the Rose institute in Claremont.

Many agree that a key lesson from the period is that the Latino community needs to build solid organizations if the country’s fastest growing minority is to become a political force.

“We’ve learned the lesson that we need cool, calculated anger, that change requires constant pressure, and the importance of organizing,” said Martinez, who as a professional community organizer has worked with such grass-roots groups as the United Neighborhoods Organization (UNO) in East Los Angeles. He now works with the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, a San Antonio-based organization that recently launched a national campaign to register 1 million more Latino voters by the 1984 general election.

Many point to such groups and to civil rights organizations like the Mexican-American Legal and Educational Fund as having resulted from the experiences of the period.

In fact, most urban 1960s activists credit the movement with a broad array of accomplishment for Latinos, including increased college enrollments, affirmative-action programs, a renaissance in art, establishment of college Chicano studies programs and academic research and more bilingual education programs.

But none deny that its most direct benefits went to a very small segment of the Latino population, primarily the middle-class, college and professional sectors.

A recent Los Angeles Times Poll showed that only about half the Latinos in California are aware that the Chicano Movement took place, a recognition rate only slightly higher than that of Anglos.

Of those Latinos aware of the movement, three out of four credit it with helping to improve conditions for Latinos. The strongest approval came from those who were 22 to 35 years old at the time and those in the highest education and income levels.

There is general agreement among 1960s activists that the movement did not bring about the fundamental changes many had hoped for.

The economic and political system that historically has relegated Mexican-Americans to the bottom or near bottom of the educational and labor pool did not budge appreciably. Conditions for the vast majority of Mexican-Americans have not improved, relative to the dominant population, and some observers claim they have actually worsened in the midst of bad economic times and a politically conservative climate.

According to Ray Roco, a political scientist at UCLA, the new Chicano professionals are “on the cutting edge in … gaining some kind of leverage on the system.”

“But we know very little about what’s happening to them,” he added. “Are they simply going to reproduce the values already there, creating distance between them and the masses of Mexican-Americans, or are they going to affect change?”

A few former leaders of the period, like “Corky” Gonzales and Reies Tijerina, have held fast to their ideals — but they have seen their influence wane with changing times.

Their younger counterparts, though, maintain that their upward mobility has not altered their commitment to the ideals of their youth.

“I know that as a generation we made a difference. And we are not dead.… We’ve come of age. We’ve become specialists in our fields. We’re still motivated, still chipping away at the institutions,” said Alurista, a Chicano poet and former student leader in San Diego. “We have people from the ‘60s generation in different spots and levels of society.... Our power now lies in the specialization of our pressure.”

But there is concern that as Chicanos “infiltrate” the institutions they once fought, the battle lines have become less clear.

Some detect a lack of commitment among Chicanos within the professional sector. These critics say that as Chicanos have become part of the establishment, many have become less willing to disrupt it. Nor do these critics buy the contention that improvements will trickle down to the masses as Chicano professionals move into positions of power.

And while many among the new professionals still view themselves as leading the way, others maintain that the focus of the Chicano struggle has shifted back to the most disadvantaged segment of the community, those with the lowest income, the highest unemployment, the least education.

Those who remember the concessions won when thousands marched in the streets maintain that Latinos’ greatest advantage still lies in their potential to mobilize mass action.

Others express the hope of linking the professional resources of those within the institutions with the masses at the grass-roots level, combining civil disobedience with political and economic power.

During the last year, for instance, a cross section of Latino groups has strongly lobbied against the Simpson-Mazzoli bills, sweeping immigration legislation that many Latinos fear will result in mass deportations and discrimination against Latinos. Some have testified before Congress, while others have demonstrated in the streets.

And, on a broader scale, Bert Corona said he sees another national movement taking shape among working-class Latinos, illegal immigrants and a cross section of other groups most adversely affected by Reagan Administration economic and social policies.

Like Martinez, the activist-turned-community organizer, many look upon the 1960s as part of a cycle, “a blip in the continual struggle of Mexican-Americans in this country....”

“Tactics and strategy may have changed,” Martinez said, “but the spirit is still alive, the same spirit that has characterized our history of struggle in the United States for generations.”

Activists like Corona, who preceded him, were “the holders of the flame,” Martinez said.

“They held on, waiting for the next generation to give birth to another era. They were the link. They provided the continuum.”

Martinez said he looks forward to “the day when the next generation comes along to challenge us and the status quo. What we’ve accomplished is not bad, but it’s not good enough.”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.