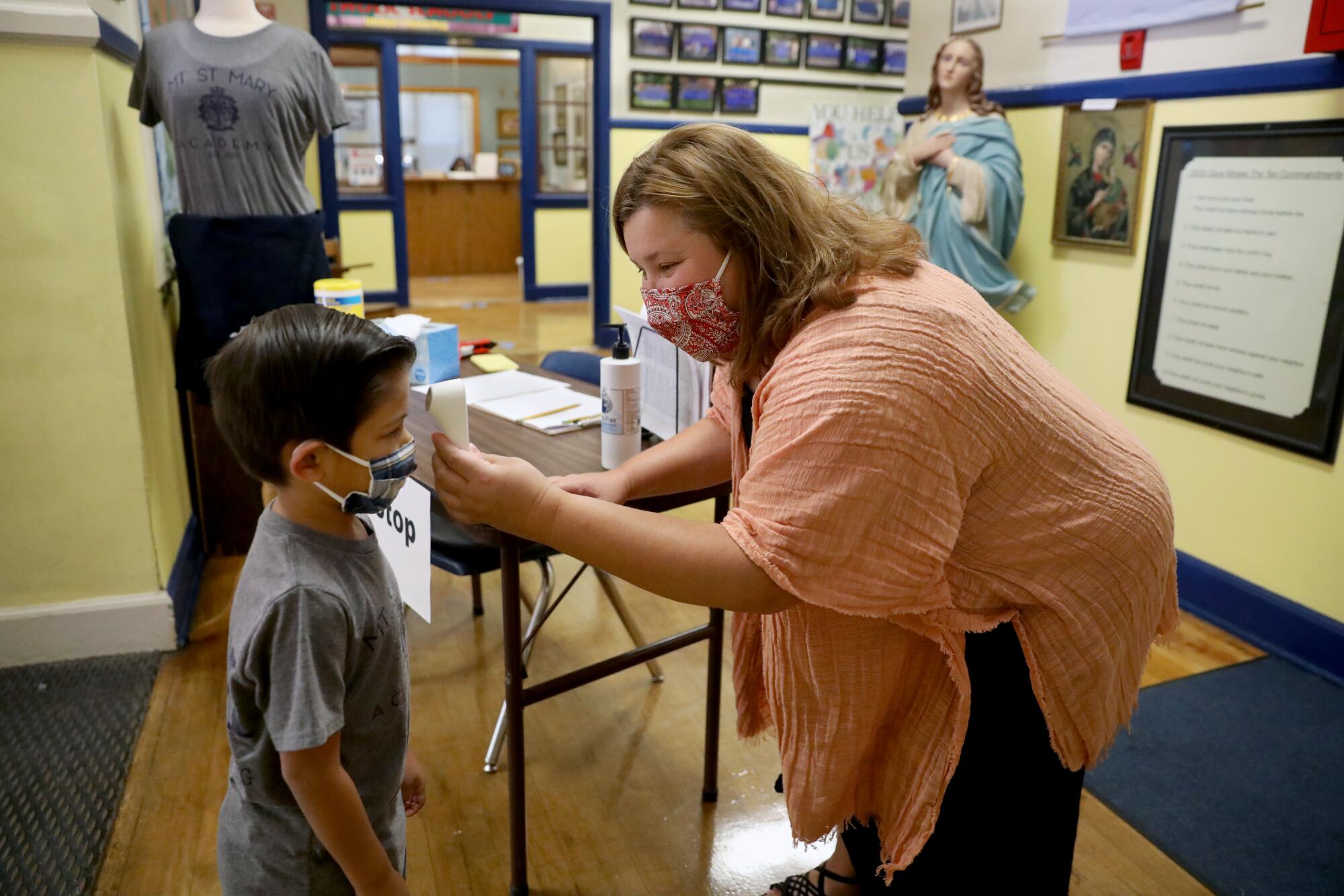

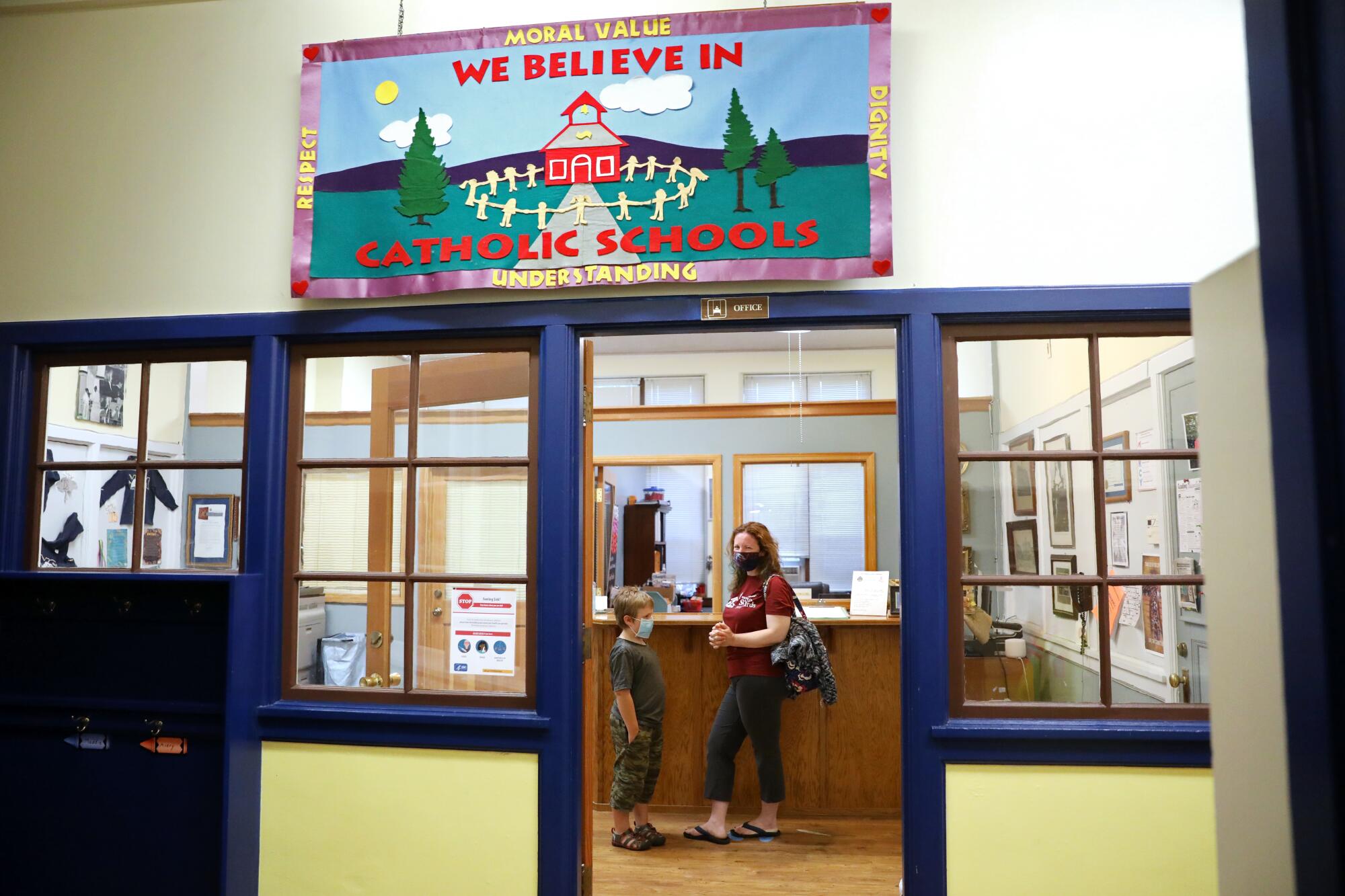

GRASS VALLEY, Calif. — Inside Mount St. Mary’s Academy, a Catholic school in this Gold Rush town in the Sierra Nevada foothills, a life-size statue of the Virgin Mary stands sentinel over the check-in table at the front door. Students returning for the fall session stop under her watchful gaze for a modern ritual of pandemic life: temperature check, hand sanitizer, questions on their potential as virus vectors.

Thursday morning, Principal Edee Wood wore a red paisley-printed mask as she wielded a digital thermometer intended to protect the 160 students at her school, one of the few in California attempting in-person classes this fall. At Mount St. Mary’s, life is going back to normal with crisp uniforms, sharp pencils and classes five days a week.

While remote learning is the rule at nearly all public schools right now, Mount St. Mary’s is opening because it is in Nevada County, which is not on the state’s coronavirus watchlist, and also because its administrators believe it can do so safely.

As parents across California struggle with plans for more at-home schooling, Mount St. Mary’s is engaging in an experiment it hopes will provide a model for other schools like it, said Lincoln Snyder, superintendent of schools for the Catholic Diocese of Sacramento, which oversees 38 campuses enrolling about 13,000 students from the capital north to the Oregon border.

While a handful of those are now back in classrooms, Snyder hopes to reopen them all in coming weeks, using plans that he has been working on since the virus first forced schools to close in March. He is on the fourth version of those rules.

“Obviously we are all learning as we go,” Snyder said. But he is adamant that kids belong in class and that smaller, private schools like his are “nimble” enough to do it safely.

How, where and which kids return to school in California is mired as much in politics as health concerns, though.

Across the state, debates are raging about the risks kids and teachers face, how children are weathering the mental health ramifications of isolation and how working parents can cope with distance learning. Allowing some schools to reopen also raises issues of equity — tuition at Mount St. Mary’s is about $5,000 a year, though many families receive financial help.

![GRASS VALLEY, CA ]\](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/b001b2a/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6411x4274+0+0/resize/2000x1333!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fcb%2F80%2F872c1b224b02935d767f71b1bb2b%2Fla-photos-1staff-587141-me-first-school-nevada-county-gxc-1202.JPG)

In Grass Valley, a place where local Wendy Ermshar said “you’ll see Trump stuff everywhere and then you’ll see Black Lives Matter stuff everywhere,” some see Mount St. Mary’s as engaging in arrogant foolishness, while others see it providing an essential service.

Weeks ago, Gov. Gavin Newsom put in place a complex rubric for when schools can resume in-person instruction in the 38 counties that have a high prevalence of the coronavirus, prompting most large districts to announce remote learning for the fall. But Newsom also created a waiver system that allowed schools with risk-mitigation plans to apply to their local health departments for permission to return to on-campus education.

As those waivers are considered in the coming months, and some likely granted, schools like Mount St. Mary’s will provide lessons on what works and what doesn’t.

Though Wood has spent months preparing to bring students back inside the old brick building, founded in 1859 and the oldest continuously running Catholic school west of the Mississippi, she is apprehensive.

“We are all nervous,” she said.

Snyder’s protocols for Mount St. Mary’s span 28 pages and cover everything he, the state or the federal government could imagine beyond the basics of hygiene and common sense: No outside food allowed; open windows when it doesn’t affect children with pollen allergies; remove all classroom rugs.

Wood has tried, she said, to imagine every step of the day for every student.

Though only kids above third grade are required to wear a mask in classrooms, per state rules, Wood ordered neck gaiters for every child so that the younger ones could pull it up as needed, without having to worry about taking a mask on or off, or losing it, she said. In hallways, blue footprint stickers with cartoon eyes create one-way paths for kids so that they don’t need to pass others.

Gone are high-fives and embraces when children greet teachers. In their place, first-graders will do what teacher Carol Kent describes as a “lobster hug,” where she faces her student from the requisite six feet, bends slightly at the waist with her arms outstretched and wiggles her fingers toward the child. In second grade, “we are just going to give compliments, maybe a namaste,” a traditional Hindu greeting with hands pressed together, said teacher Carol Keane-Stein.

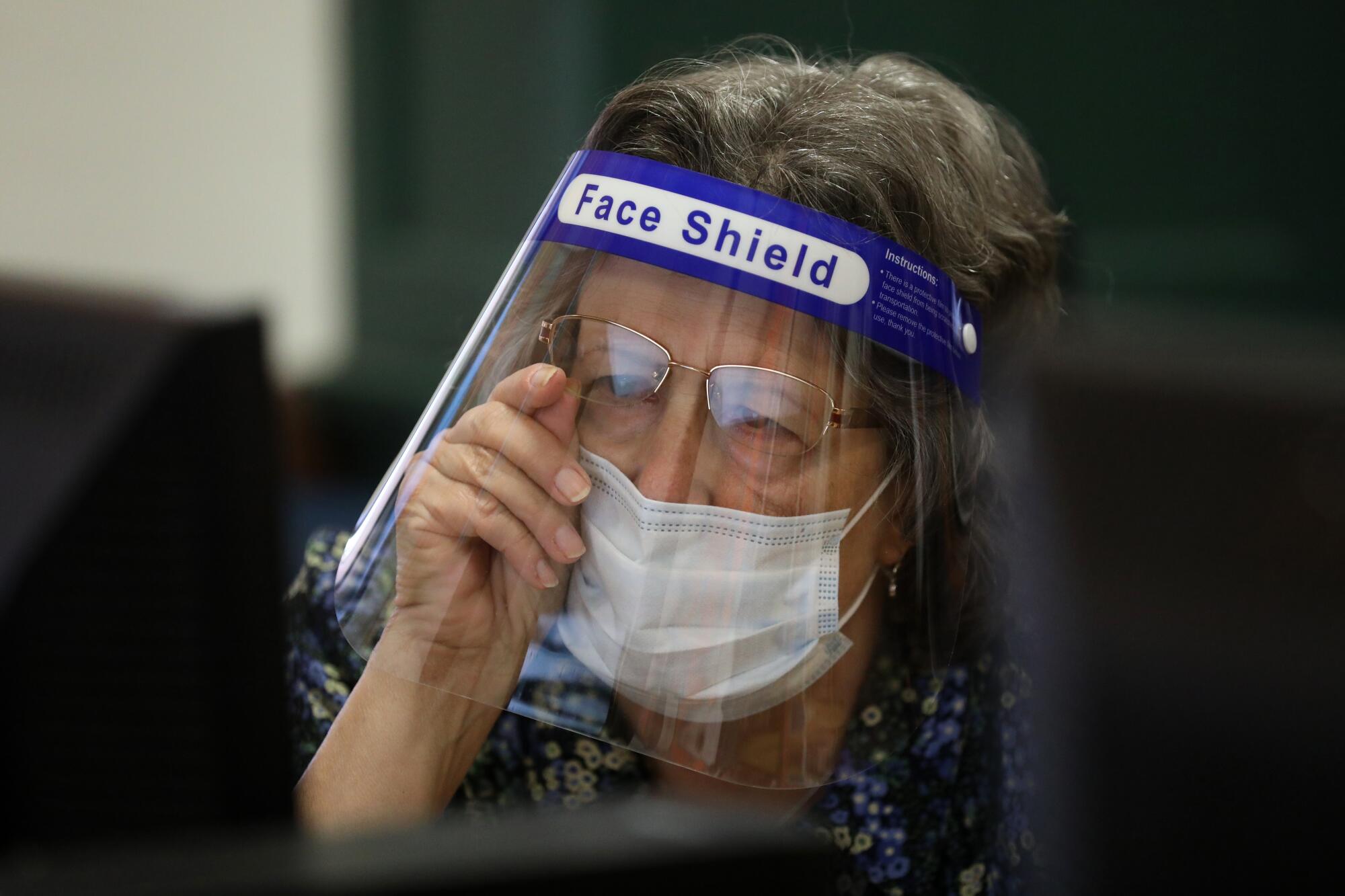

Kindergarten teacher Megan Hood, starting her first year at the school, is opting for a face shield instead of a mask so kids can see that the “t and the h make a th” sound, she said.

“It’s just a good time to think creatively and outside the box,” Wood said.

But Wood and her teachers say that old-school methods will be a big part of the future. After years of moving toward teaching models that invited collaboration and group work, kids will now be sitting at desks all day — even Hood’s “littles,” as the kinders are sometimes called.

“It’s basically going to be like when I was in school,” said Kent, the first-grade teacher. “But every half hour we are going to get up and wiggle or stretch or dance to rock and roll.”

Parents, teachers and administrators all agree that the small size of Mount St. Mary’s, and other schools like it, gives them an advantage in combating COVID-19. Even before the pandemic, classes topped out around 20 students — leaving its large classrooms, most with 20-foot ceilings and ample windows, with plenty of space for separation. Its wood-planked halls with bright yellow walls smell of cool plaster and mountain air from the redwoods and maples that surround it. Outside, a blacktopped play area has a covered pavilion with lunch tables.

The smaller community has also allowed for more consensus. Though online learning will be offered, Wood said most parents want in-person lessons.

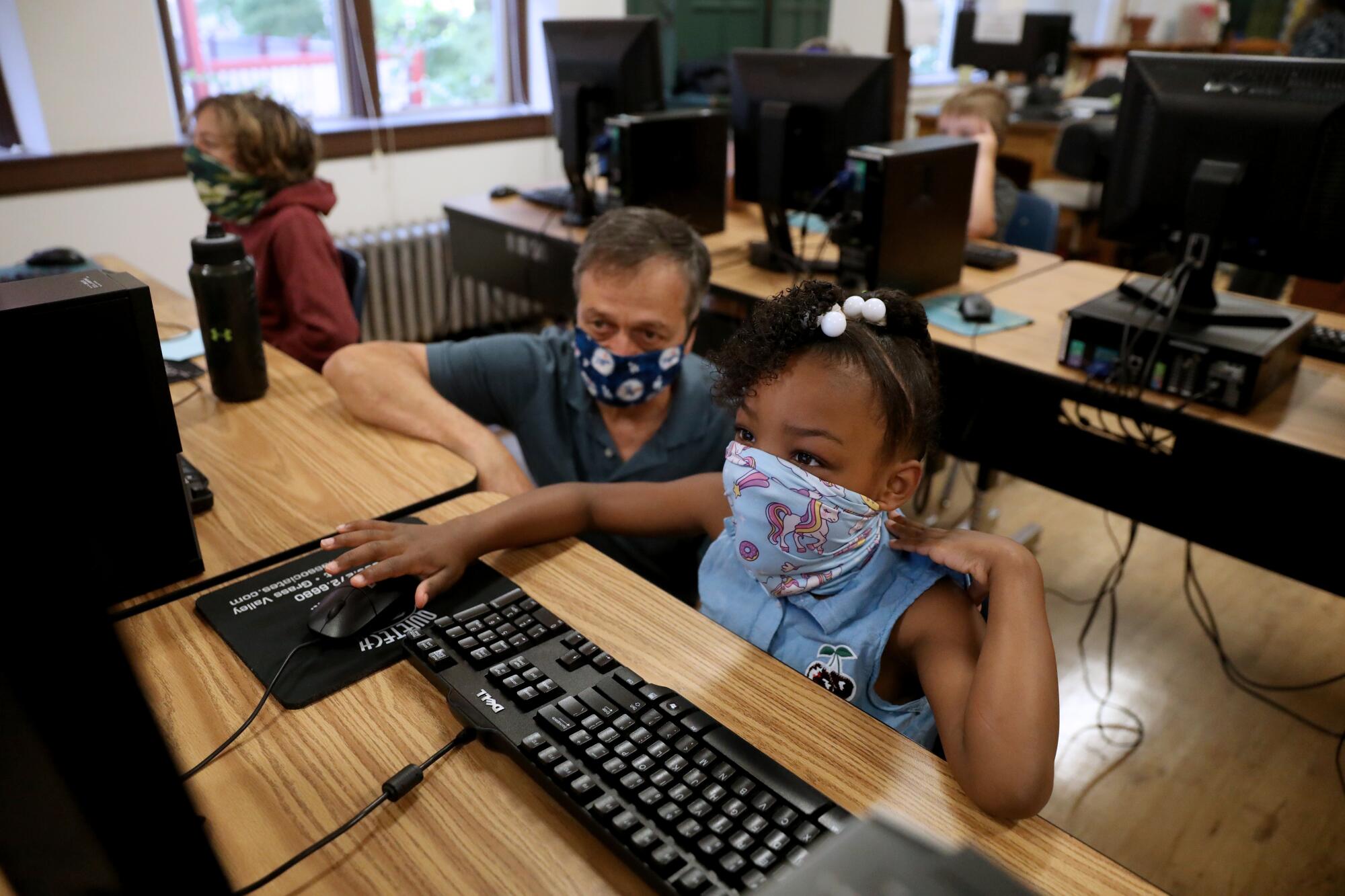

Nora Roe is one of those parents. With her son Hunter, 6, Roe met with Kent on Thursday morning to help him pick out his desk and take a math assessment test. Hunter sat socially distanced from Kent, who wore a face shield, as he clicked through problems on a computer in a lab where every other machine was blocked off.

Roe said she believes the mental health consequences of being out of school are more harmful than the risk of illness, and that Hunter is eager to be back.

“If you tell him school starts in an hour, he’ll be dressed, waiting on the front porch,” she said.

Amber Waters, who was with her daughter, China, 8, and son Jaeden, 10, said she is “cautious but excited.” Both she and her husband work full time for the U.S. Forest Service, he as a firefighter, and she believes the danger of the coronavirus in a school is less than her spouse will face in a fire camp. She, too, said the “family aspect” of the small school made her trust “that they are not going to put our children at risk.”

For many students, the chance to be around other kids is a relief after what many said was a lonely summer.

Ema Chapman, 13, is starting her eighth-grade year. Since the pandemic, she’s done little but ride horses, she said.

“I’m really excited,” she said of being back on campus. “I’m really looking forward to it.”

Despite the unknowns, enrollment is up at Mount St. Mary’s. Third grade has a waiting list and most other classes are full. Applications, said Wood and some teachers, went up as soon as people learned it would open regularly.

Parent Kimberly Penrose said fights with her fourth-grader Bryson about completing online lessons were “hurting our relationship.” She moved him from a public school to Mount St. Mary’s because it was in-person.

“The distance learning wasn’t working for us at all,” she said.

Mount St. Mary’s opening is also aided by the fact that its teachers, like most of those in private and parochial schools, are not unionized. Across the United States, unions have been vocal in demanding that the virus be brought under control before teachers return to classrooms, to protect both their own health and that of the community. In some states where schools have opened, outbreaks have already occurred at public campuses.

Like their principal, teachers at Mount St. Mary’s said they are concerned, but think the school is doing everything that it can to ensure safety. Snyder said that if a teacher was uncomfortable returning, they would treat “it just like we would any other medical leave accommodation,” but so far, none has declined to go back.

“We are going overboard,” said David Pistone, a middle school teacher who used to be an engineer at Intel. “I am surprised my hands are not falling off from the bleach.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.