California unemployment agency workers say internal problems are stalling claims process

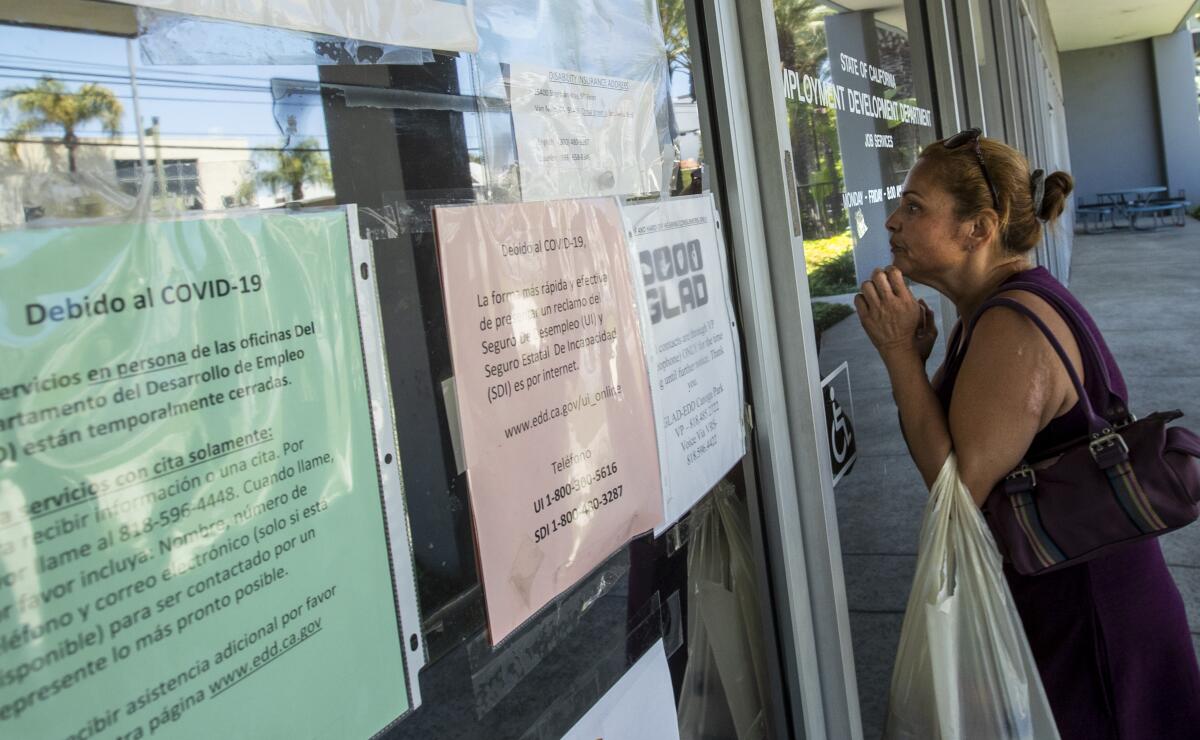

SACRAMENTO — As California grapples with a deluge of requests for unemployment benefits amid the COVID-19 pandemic, some state workers processing claims say they are buckling under pressure, hampered by outdated technology, bureaucratic red tape and a shortage of trained, experienced staff.

The state Employment Development Department is so overwhelmed that Gov. Gavin Newsom acknowledged last week that nearly 1 million unpaid claims may be eligible for payment but require more information, with estimates that the backlog won’t be eliminated until the end of September.

Inside the EDD, full-time employees and temporary hires say they are working long hours, including weekends, but often feel helpless to resolve problems for desperate Californians who have been out of work for months and often call crying or angry.

In interviews with The Times and testimony during a legislative hearing last week, current and former EDD workers say they have been hindered in assisting those who have lost jobs. Some EDD workers are so frustrated with the process that they have quit.

Laura Stewart, who has worked for the state for almost 25 years, most recently in purchasing at the Department of Veterans Affairs, was among the state workers transferred to the EDD in a bid by the agency to address its ongoing issues. She said she “saw it as an opportunity to help my fellow Californians.”

But she was unprepared for what she walked into, she said in an interview.

Stewart underwent training that was conducted completely online because of COVID-19. She was given an 800-page instruction manual that contained numerous possible scenarios for unemployment claims and said she was left to fend for herself.

When she started working on claims, the agency’s old computer system and confusing regulations made work difficult. She was promised a mentor but never received one, she said, and her supervisors changed every week. She said many were unwilling to give her the time on the phone she needed to resolve problems.

In some cases, claims stalled because of a small error. One person filing a claim with the correct date of birth saw their claim stall when the date was somehow changed after it arrived at the EDD.

Stewart said that whenever she needed help, supervisors were unable to pull up claims she had on the screen of her state-issued computer at her Sacramento-area home. As a result, she had to send them a screenshot and make changes herself based on their instructions — if they could figure out what was wrong.

“I know I’m part of the problem because I don’t know what I am doing,” Stewart said. “I really feel bad for anyone trying to deal with EDD — particularly if they obviously do qualify for unemployment funds. The system is so inefficient on so many levels.”

As a result, Stewart decided to quit late last month after nine weeks at the EDD and said she plans to go to another state agency where things are less dysfunctional.

“I just got so frustrated with their technology, their antiquated systems they are trying to use, and the whole training program that was ridiculous,” Stewart said.

Samuel Kihagi, an amateur filmmaker, voiced similar concerns to The Times before he quit his job Tuesday. He was brought in to answer phones for the EDD through a staffing agency for $16 an hour.

Kihagi, who was hired in June for an assignment to run through at least August, said he does not believe the six days of training he received were adequate and noted he was severely limited in what he could do on his home computer. For example, Kihagi said, he was not given access to purge or lift certain disqualifications to resolve claims for people who called.

As a result, he had to rely on information on the EDD website, which callers can access, and fact sheets to answer general questions and inform callers about the rules. He was often forced to end a call without resolving issues that were stalling payments.

“I feel frustrated,” Kihagi said. “When we have someone who hasn’t had their money for months and they are calling this line, and they get me and all I can do is tell them, ‘Your payment is pending and I can’t do anything for you,’ that to me is kind of pointless.”

Kihagi said that the system allowed him to forward problem claims to specialists but that technical flaws prevented him from including notes identifying the problem, potentially delaying resolution.

Callers have cried when they realized he didn’t have access to the system to look at their account, he said. Others have gotten angry.

In order to avoid being yelled at by frustrated callers, “I have told them someone will contact them about their claim in a few days when I know that couldn’t be further from the truth,” Kihagi said.

The EDD currently has a four- to six-week wait time for workers to call back customers with problems, according to agency officials.

Department veterans also say they are being pushed to their limit. Tracie Kimbrough, who has worked at the EDD for 10 years, told lawmakers at a hearing Thursday that she and many of her co-workers “have to take breaks to go away and shed a few tears when hearing heartbreaking stories from other Californians.”

“Many times we are not able to do what is needed to assist our claimants [because of] outdated technology, limits on what we are allowed to do,” said Kimbrough, who answers phone calls from jobless people seeking help with their claims. “We are not empowered, even if we have the skill set to do what is needed in order to help our claimants.”

Charles Tate, who was redirected from another state assignment to work in the EDD’s virtual call center, said he sometimes works 10 to 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

“The understaffing and outdated technology really stands in the way of EDD providing customer service during this time of crisis,” Tate told lawmakers.

Some EDD workers are so frustrated that they have advised callers to seek help elsewhere.

“Constituents have called the EDD helpline and were told that they should call their elected officials to help with their claims,” Assemblyman Tom Lackey (R-Palmdale) complained to EDD Director Sharon Hilliard during the hearing.

“I’m sorry that has happened,” Hilliard responded. “We have clarified with our staff to make sure that doesn’t happen in the future. That is not our policy.”

The director acknowledged last week that the EDD was unprepared for the unprecedented 9.3 million claims from people who lost jobs or work hours since the pandemic began in March, more than double the number of claims filed during the worst year of the Great Recession.

With relatively low unemployment before the coronavirus struck, the EDD in March had just 20 workers assigned to the task of verifying the identity of people filing unemployment claims and 1,250 staffers to process claims — including 350 claims experts who answered calls from applicants for four hours a day, from 8 a.m. to noon.

In response to the surge in new claims, the EDD redirected 626 of its employees to help with claims processing and brought in 700 workers from other state agencies. The department also is hiring 5,300 other workers to help out.

Even so, many unemployed Californians say they have had to make hundreds of calls a day to the EDD before someone answers, only to be told they can’t be helped.

Frustration has sometimes boiled over into anger at department officials, including in other states where employment systems have been overwhelmed. Nevada has seen three top officials with the state Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation step down in recent months. The Nevada agency’s interim director left her job June 19 “due to threats to her personal safety,” according to the Nevada governor’s office.

California EDD workers are continuing to process claims “despite the bombardment of negative sentiment,” said Barbara Fales, a longtime EDD employee who was redirected to help with the Work Sharing program that helps employers avoid layoffs by paying part of the wages of employees.

She noted that the program still relies on paper forms that must be mailed back and forth to employers and employees.

Fales said part of the problem is the mass hiring through private contractors, which she said has resulted in “poor performance by low-paid workers with inadequate training” and a lack of experience.

“We understand we are the lifeline for many struggling Californians, but we are understaffed and underfunded,” she said.

State officials say they are acting on many of the concerns they have heard about the unwieldy system and lack of training.

“We continue to enhance the skills of our folks every day,” Hilliard said. “We have people coming out of training every week that are fully trained for claims processing.”

More trained workers will be incorporated into a merged call center system that, starting in mid-October, will route calls to agents who specialize in the problems affecting the callers.

Newsom last week created a “strike team” to develop a plan in 45 days for improvements at the EDD, including fixes and eventual replacement of the computer system.

Though millions of claims have been processed and improvements have been made, “too many Californians who may be eligible for benefits have not been paid,” Labor Secretary Julie Su wrote in a letter to the Legislature last week. “We must do better.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.