Newsletter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

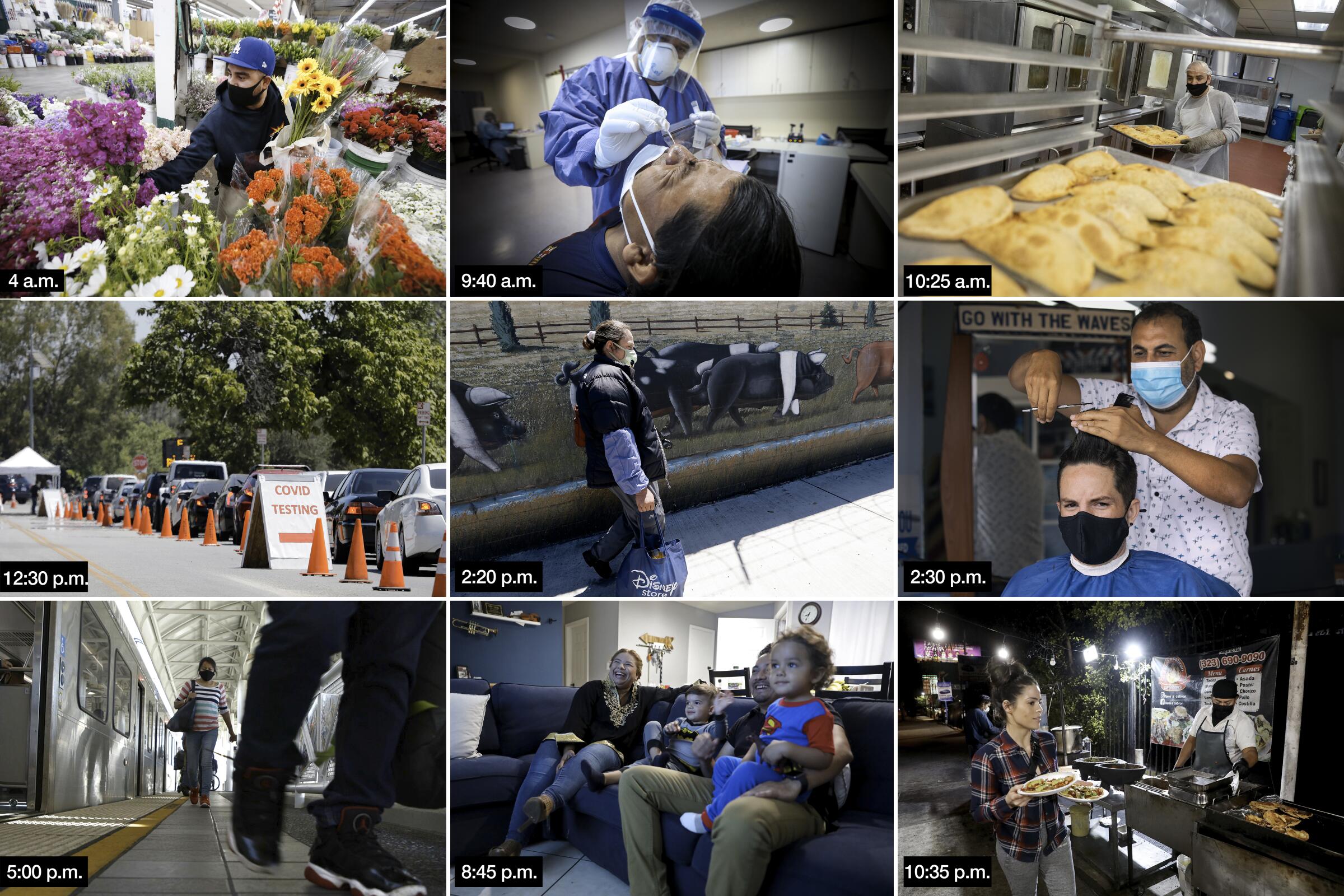

The pandemic may have slowed the city, but it hasn’t stopped it.

Starting well before dawn, essential workers toil at factories and markets and restaurants. Some remain deep into the night; the lucky ones work from home. Parks and beaches and hiking trails beckon those desperate for a break.

But COVID-19 has not been an equal-opportunity scourge. Those who see no choice but to work outside their homes are far more exposed than those who have the luxury of sheltering in place. Those in crowded households are far more likely to fall ill than those who live alone or in small families.

A Times analysis, based on Los Angeles County data, shows that someone living in the heavily immigrant Pico-Union neighborhood, for example, is seven times more likely to contract the disease — and 35 times more likely to die — than someone in relatively affluent Agoura Hills.

The Times sent reporters across the city to capture one day, Wednesday, in the life of the coronavirus pandemic. Here is what they found:

Most of Los Angeles was still asleep, but the heart of L.A.’s flower district on Wall Street was already full of life — of both the human and plant variety — a cacophony of color. Buckets of lilies, roses, baby’s breath, chrysanthemums, sunflowers, hydrangeas and daisies were being carted through the cavernous Original Los Angeles Flower Market.

The market reopened May 7 after being shut for two months due to COVID-19.

“We are all adjusting to the new norm,” said Qiana Rivera, as she separated bunches of green fronds. One of the market’s vendors, Rivera is grateful to be back at work. “It was so nice to come back and see our regular customers.”

But it’s been challenging too. Many vendors, like David Ramirez, say business has suffered tremendously. Ramirez is barely breaking even: “We are just trying to survive,” he said.

Most of Los Angeles was still asleep, but the heart of L.A.’s flower district on Wall Street was already full of life.

Summer is typically peak wedding season, a lucrative time for the flower market, but most gatherings and celebrations have been postponed or canceled. “This should be a good season for us, but we are really struggling,” Ramirez said.

It’s not just the sellers who are having difficulties. During the two-month shutdown, growers across California threw out thousands of flowers and lost millions of dollars.

Many Flower Market customers are florists doing their best to drum up work despite the decline in events, but individual shoppers have also begun to visit the market again too.

Charlotte Redmond, a phlebotomist who is now testing people for COVID-19, stopped by before work.

She was browsing the house plants, looking for pothos and air plants. “Testing for COVID all day is wearing me out,” Redmond said. “My happy place is my garden now — the plants make me feel peaceful.”

—Chace Beech

Drop-off was just beginning at the Little Armenia Day Care when owner Abram Mutafyan sat down for his third cup of coffee. On the desk in front of him were several pairs of eyeglasses — he’s diabetic, so his prescription changes — and a half-empty carton of Capris, which he went back to smoking last year after his second heart attack.

Little Armenia, which ranges north of Sunset Boulevard between Thai Town and East Hollywood, has had 43 COVID-19 deaths, enough to give it the highest COVID-19 death rate in Los Angeles County — 535 per 100,000 population, nearly 25 times the statewide average. It’s a densely populated neighborhood where long-term care facilities have helped fuel the pandemic.

“They’re saying [coronavirus] is more dangerous for people my age, people with diabetes and heart problems — I have all of those,” the 67-year-old sighed, his mask puffing. “I was really badly scared and I would really love to close, but there’s too many families that depend on us.”

Among the center’s 40 students are several children of nurses, and a disorienting number of twins. A few were studying butterflies — t’it’err, in Armenian. Their pet monarch had just emerged, and teacher Lucy Urfalyan read “The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” translating in situ, her hair spilling over her face shield in gold ringlets. Most read along brightly. But since the pandemic, a handful were moody.

“David, what was your favorite part?” the teacher asked a sad-eyed 5-year-old in a fresh pandemic buzz cut and an Armenian coat of arms T-shirt.

“I don’t like it anymore,” David answered in English.

“Why?”

“Because I want to go to Yerevan. I want to go on an airplane to my grandma and my grandpa.”

—Sonja Sharp

The nurse practitioner knew the word coming out of his mouth was laughable when he said it.

“Relajate,” said Willie Rios, as he stuck a 6-inch long Q-tip-like swab up a woman’s nose. “Relax.”

It was 9:40 a.m., about an hour after St. John’s Well Child and Family Center opened, and Rios had already given more than a dozen people before her the same advice. Cecilia Soriano was the 15th person called into the yellow and blue one-story house turned into a COVID clinic in South L.A.

It wasn’t her first test, but Soriano still squeezed her eyes tight and leaned her head back as far as her neck would allow while Rios swabbed each nostril. Soriano tested positive at the end of April, but the 29-year-old wanted another test because her eyes hurt and she felt congested. Within seconds, it was over.

“Here come the tears,” Soriano said as she wiped her eyes with a tissue. Results would come in two to three days.

At the Williams Clinic on 58th Street, providers have tested nearly 8,000 people since March. There are close to 500 tests done a day in all the center’s testing sites. The center has added staff just to meet the demand.

This morning, some people arrived an hour and a half before the clinic opened. Some were there for regular appointments or to pick up medication. Those who wanted testing or who were symptomatic were directed to the building next door.

Those patients sat outside masked and in chairs six feet apart, their coughing mingling with the songs of Sonora Dinamita being blasted by a woman selling dishes, stereo equipment and fans outside her home across the street. A few people lined up on the sidewalk outside.

Many of the patients had been exposed at work or by family members who were working. Esteban Soto rested his hands on his blue pants and tapped his New Balance sneakers on the concrete as he waited his turn. The 65-year-old, who repped his home country of Guatemala on his yellow T-shirt, showed up because two people he worked with at a panaderia in South L.A. had tested positive. Now Soto’s throat hurt and he had a sporadic fever.

Despite his symptoms, he was considering working the next day because he needed the money. He hoped the result came back negative.

“If not, I’ll have to isolate,” Soto said. “I don’t know if they’re going to keep paying me.”

—Brittny Mejia

Golden brown oil crackled in the Union Rescue Mission’s deep fryer as O.J. Hutson cut open a bag of frozen french fries.

The 46-year-old chef moved the fries through the oil while the kitchen’s manager, Delilah Cannon, 28, offered thoughts on what they should serve for lunch to the Skid Row homeless shelter’s residents next week. Hutson offered a deep, raspy laugh through his mask at her entreaties about what to cook.

“What soup are you gonna make?” she asked. “I like creamy soups. You like brothy soups.”

They resolved that BLTs would be served for lunch next Monday along with tamales for breakfast. His kitchen is less crowded these days — fewer volunteers are allowed on the premises and there are fewer people living in the facility.

A spring outbreak of the virus left over 100 shelter residents and staffers sickened and two people dead. This outbreak transformed the shelter, which normally sleeps upwards of 1,200 people — and how food is served in particular.

Now around 320 residents are allowed to stay inside after shelter staff hustled people into hotels provided by the county in an effort to distance people at risk of dying from the virus. Food donations are only now returning to what they were pre-pandemic and still Hutson is serving half as many meals as he did prior to the pandemic.

“Everything is upside-down. Whatever our normal was seems like a fantasy,” he said. “There’s the anxiety. The stress. The depression. The not knowing. We’re being careful but the same routine just isn’t the same anymore.”

—Benjamin Oreskes

Sweltering midday heat wasn’t enough to stop masked customers from patronizing the strip mall on the corner of Foothill Boulevard and Osborne Street.

Thirty years ago, the intersection was the site of the Rodney King beating, a grim yet defining moment in L.A.’s racially charged history. Today, it’s home to a carniceria, a convenience store and a chicken shop, all open for business as lunchtime arrived.

Andy Lopez, an employee at the convenience store, said he’s grateful that “99% of customers” who come into the store wear masks. It’s the 1% who don’t that concern him.

“It’s something you can’t play around with,” he said of the virus. “Even if you’re big and strong, it can take you down.”

Just up the block in Hansen Dam park, golfers hit balls while hikers traversed an outdoor trail, even as a half-mile-long line of cars queued up to enter the park’s bustling COVID-19 testing site.

One family took a nap on a blanket under a tree, unaware, they said, that Lake View Terrace is one of the communities hit hardest by the coronavirus in Los Angeles County.

Alfonso Star, who was drinking beer and listening to music with a group of his friends, said he was outraged that COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting Black and Latino people, and insisted that it’s impossible to separate the country’s current racial tensions from the virus’s deadly toll.

Star blamed President Trump for the mess, noting that the phrase, “I can’t breathe,” uttered by George Floyd before he died at the hands of a police officer, is equally applicable to the ravages of the respiratory disease.

His brother, Frank Star, was fatalistic.

“If it’s your time, it’s your time,” he said. “My creator’s got me.”

—Hayley Smith

It’s a busy day at Paradise Pictures, albeit a quiet one.

Besides writer and producer Allison McGourty, there were just two others in the spacious craftsman in Santa Monica, and they were in a dark room with masks on editing a documentary about Led Zeppelin. Before the pandemic, there would have been others working behind monitors in various corners of the suite. Now, in this new normal, most tasks are done remotely, which means McGourty spends much of her days in Zoom meetings.

McGourty’s day began at 7 a.m., with a call to her post-production team in London. She should have been there with them, overseeing the color grading on the documentary that requires a deft technical and artistic touch. She also should have been able to attend the funeral of a good friend who died recently. But that is not the world she is living in.

Now McGourty was sitting at her desk, which faces a row of open windows. There was a light breeze, and she could see Santa Monica Beach just beyond the tropical plants in the front yard, where hummingbirds are known to flit around.

She called her archive producer in the U.K., and they talked about how they would get the last bit of footage they needed before the archive house in France closes for the August holiday. It’s been difficult to get all the footage they need. The pandemic shuttered European archive houses for months, and now they must rush before the houses shutter again.

Yet another video conference call awaited. The calls can seem endless, but she has noticed lately that people seem to be more respectful of time. There are fewer emails sent, less fluff.

For this — and the fact that she and her team members are healthy, and that all of their shooting was done before the pandemic hit — she is grateful.

—Laura Newberry

Rina Chavarria could barely lift her brown steel-toe boots as she walked out of the employee entrance of the Farmer John meatpacking plant in Vernon.

It had been a long day. The 52–year-old had been awake since 3 a.m. and had been at the meat packing plant since 5 a.m., standing on the cutting line, removing excess fat and bones from 6,750 pork loins.

It had been her first day back after being away from work for two weeks after a co-worker she had given a ride to had tested positive for COVID-19.

She had also been infected in March when an outbreak occurred at the plant.

But now, she was outside. The sun was warming up her cold hands and she was trying to take in air through her baby Yoda mask.

She made her way to the parking lot more than 800 feet away. There she opened the trunk of her blue, four-door Toyota. She took out sanitizing wipes and began to remove her boots, then her hiking pants — an extra layer to protect her from the coronavirus, she said. She threw sandals on the ground and put them on after removing her socks.

“This is my routine,” she said. “Every day.”

She began using the sanitizing wipes to clean her boots.

“You never know how you catch this coronavirus,” she said.

—Ruben Vives

John Settles had just finished getting his hair cut. The Rancho Palos Verdes resident stepped out of the barber’s chair and turned to check out the results. In the window of a nearby BMW.

Because the mirror at Waves Barbershop & Boutique is inside the tiny ocean view shop on Rosecrans Avenue. And the haircuts happen more or less outside, now that California is on its second COVID-19 shutdown and the only legal salon is an al fresco one.

It’s hard to have a more Southern California experience than an open-air grooming session in tony Manhattan Beach, even with a late-season gloom and a slightly chilly ocean breeze.

That didn’t stop Faro Tabaja, Waves’ owner, from flinging open the shop’s French doors first thing in the morning, dragging the shiny barber’s chair to the very edge of the shop and placing it so the footrest — and his clients’ feet — stuck out of the storefront and over the sidewalk.

Men awaiting a much-needed trim cooled their heels in a pair of office chairs Tabaja had positioned across the sidewalk, hard by the parking meters. A surfer — wetsuit peeled to his waist, board tucked under his arm — headed to his car. A woman with pink hair strolled by with a pair of French bulldogs.

“I have a mask on,” Tabaja said as he snipped away at a client’s salt-and-pepper locks. “He has a mask on. It’s a different life.”

Two miles east on Rosecrans, in the Manhattan Marketplace strip mall, Posh Nails also was doing a brisk outdoor business. The seven sidewalk stations were full. Manicurists in full protective gear bent over clients’ hands, filing nails, scraping cuticles, brushing on polish.

Women soaked their feet, pre-pedicure, in plastic-lined tubs. An armored car rumbled by, followed by a UPS truck. Where the outdoor nail salon ended, a half dozen shoppers lined up (six feet apart, of course) waiting to get into Helen’s Cycles.

In Manhattan Beach, Posh Nails offers outdoor manicures and pedicures on the sidewalk after Gov. Gavin Newsom announced new guidelines allowing nail salons and hair salons to operate outdoors.

Jan and Hillary Rosenfeld were out for a late afternoon manicure, a little mother-daughter bonding before Hillary leaves for the University of Wisconsin. Jan has waited out the pandemic in her Manhattan Beach home, cooking, phoning distant relatives, picking up a new hobby or two.

But on this afternoon, she was really, really happy to be outside getting her nails done.

“It’s nice to be able to pamper yourself,” she said, adjusting her slipping face mask. “It feels like a little bit of normalcy.”

— Maria La Ganga

To prepare for “Abstracting the Landscape,” the class he teaches at the Brentwood Art Center in Santa Monica, Rob Homsy set up two cameras, one aimed at his palette and another on his canvas.

Students of all ages and skill levels have taken classes at the center for the past 50 years. During the pandemic, Homsy has found that teaching painting, with all its shades and textures, is difficult online, but he does his best to describe colors that are not done justice by the cameras.

For an hour and a half, his 12 students paint alongside him. In some moments, there is only the sound of brush on canvas and a pleasant feeling of everyone doing the same thing in the same space, albeit virtual.

With about 15 minutes left of class, Homsy checks in with his students to see their progress. It’s up to them whether they want to share, but he is eager to see their work. It’s not the same as painting in the studio, where Homsy could walk around and check on students while they worked. Still, he welcomes emails after class from students asking for extra help, and he is quick to offer suggestions.

The center doesn’t plan on reopening until next year, and when it does it will be in a new space. Until then, Homsy and the other teachers will make do. One upside to the pandemic: Students from far away have shown up on Homsy’s computer screen, some of them returning to a place where they painted as children.

—Tiffany Wong

Metro Blue Line commuters adjust to life amid COVID-19. Much of the route serves South L.A., an economically disadvantaged area where residents must show up to work even as the infection runs rampant through the city.

The A Line station towers above busy Slauson Avenue, where the bells of the incoming southbound train intersect with the whoosh of rush hour. Trains stop, people scurry out, masked and unmasked, to catch their next transfer.

Lashantay Robinson was waiting with a shopping bag on her shoulder for the train to take her to the Superior Grocers near the Florence A Line station.

Like many others riding the A Line, taking public transit is her lifeline. Without it, she wouldn’t be able to shop at her nearest grocer, or go to her job a few miles north. It may not be the safest option, but it’s the only way to provide necessities for her family.

A train came barreling south. “FACIAL COVERING REQUIRED,” it read across the front. It stopped, and inside, there was a clear pattern: one person to each set of two seats. Adjusting her pink and white polka-dotted face mask, Robinson entered and took an available seat, distanced from other masked riders.

Robinson, who lives in nearby Vernon, considers the A Line safer and more reliable than buses, which she now avoids even if it means being late to work,

“My life is more important than a job right now,” she said with a shrug. “Even though I do work because I have kids to take care of, I still have to think about me going home to my kids.”

—Astrid Kayembe

It wasn’t a typical day for Natalie Chavez and her family.

On a usual day, her husband, Eduardo, would be coming home from his security job at Kohl’s. He’d take off his shoes before coming inside, shower and put his dirty work outfit into a separate hamper. Then he’d play with his toddlers — who eagerly wait for him all day — before bedtime.

“They won’t go to sleep unless dad is home,” Chavez said.

But today was different. The family spent the day putting the finishing touches to Chavez’s sister’s mid-pandemic wedding. The family returned home from the rehearsal outside the church where the bride and groom will tie the knot — all while wearing masks.

The couple had booked a venue and planned a large wedding with 200 people. Now it’s just close family. During the reception, seats will be distanced and sanitation stations will be spread around the backyard.

“It’s bittersweet,” Chavez said. “Since she’s so excited, we’re trying to not look at the negative.”

Still, there’s a sense of worry in Chavez’s voice — after all, the family recently got tested for COVID-19 after Eduardo’s grandmother and several aunts tested positive. They’ve since recovered, but her father-in-law is diabetic and at a higher risk.

In just a week, Chavez will be in back-to-school mode. As a high school Spanish teacher, she’s expected to teach her students remotely. She’s not sure how things will work given that she has her toddlers to take care of as well. Perhaps her in-laws will take over, maybe her own mother.

For now, she’s claimed a corner of the family’s garage that serves as a bedroom for her work space.

“For a 3-year-old to understand that mom is here, but can’t talk to you is going to be very hard,” she said.

—Tomás Mier

From the corner of Atlantic Boulevard and Verona Street, a cloud of white smoke dispersed into the chilly night air. Christmas lights on a string lit the griddles of the taco stand. The street was sleepy and empty, except for the few people looking for a late-night meal.

Francisco Arizpe, 38, manager of Tacos a Cabron, swiftly chopped the meat he’d just sliced from a spinning grill. He plopped it onto several small handmade tortillas and poured a generous dollop of red salsa on top.

From 5 p.m. to 1 a.m. daily, Arizpe and his coworkers serve 200 to 400 hungry customers, sometimes more. In the early days of the pandemic, sales dropped, several employees took time off, and the restaurant was forced to offer to-go orders only. With coronavirus cases surging in L.A., they’re considering going back to that.

“We get a lot of people, so you have to be really careful and take precautions,” Arizpe said in Spanish. “We all have families.” He worries about bringing home the disease to his pregnant wife and two daughters, his “princesses.”

As COVID-19 cases surge in East Los Angeles, Francisco Arizpe talks about how he and the staff at Tacos a Cabron stay safe.

Nearby, customer Osvaldo Navarro, 25, sipped agua de jamaica and took bites from his al pastor tacos. The El Monte resident had recently finished his 15-hour shift as a FedEx manager and was here with his girlfriend for some of his favorite tacos.

“This is my dinner, and lunch, and breakfast,” he said, laughing.

Navarro is one of the lucky ones, with a job that is in high demand. But the long days have been hard, and he understands the risks. He does his best to stay safe.

He takes the last bite of his taco. He and his girlfriend hop into the car. It’s nearing 11 p.m. He’s exhausted. He turns on the headlights and ignition and drives into the night.

—Dorany Pineda

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.