George Floyd protests: Black police officers see fight for racial justice through personal lens

After days of protests over police brutality in Los Angeles County, a young sheriff’s deputy on the front lines reached out to her commander, reeling.

As a Black woman, she wanted to show solidarity with her community in grieving the brutal police killing of George Floyd. But as a law enforcement officer, she feared backlash from her peers if she were to take a knee.

“My comment to her was, if it’s genuine, if that’s how you feel, we’re not going to criticize you,” said Cmdr. April Tardy, who also is Black.

That personal conflict highlights the delicate duality of being a Black police officer in America during this moment of unrest.

In interviews, Black law enforcement leaders said they are uniquely equipped to understand the racism embedded in the criminal justice system, the history of oppression of their community and how that has sowed decades of distrust of the police. They see themselves in a position to bridge the differences.

But working within the system, some acknowledge, has not always yielded changes in policies or behavior. And recently, Black officers also have been on the receiving end of racist slurs and derogatory remarks while on the front lines.

San Francisco Police Chief Bill Scott said he is deeply aware of and sensitive to both sides of the debate engulfing the nation over racial justice.

In an interview, he recounted personal incidents that remain indelible: “For sale” signs going up when his family moved to a mostly white Alabama neighborhood in the 1970s, being in stores where an employee eyed his every move, hearing car doors locking on the street as he walked by.

“Growing up in that environment you can’t escape the fact that you’re Black,” he said.

Experts said that moving forward requires a culture shift in policing that goes beyond diversifying the ranks and prioritizes honest conversations about long-standing harmful practices.

Hiring more officers of color means little if they’re not placed in leadership positions or empowered to speak out against wrongdoing, said Rod Brunson, a professor at Northeastern University’s School of Criminology and Criminal Justice.

“Inclusion is bringing people into an organization, and hoping they don’t adhere to particularly bad practices but they help to change the culture of policing from within,” he said.

According to the Pew Research Center, surveys in 2016 of law enforcement officers found that 72% of white officers said the deaths of Black people in America during police encounters were isolated incidents, while 57% of Black officers said they are signs of a systemic problem.

But as important as who polices communities is how they’re policed, Brunson said. At least two of the officers involved in a widely publicized incident in May in Atlanta where two college students were Tasered were people of color, he noted. One of the four officers charged in Floyd’s death is Black.

An officer’s race “doesn’t magically insulate people from poor treatment,” Brunson said. “There’s also an organizational demand. So what type of behavior is expected and culture is tolerated and, more importantly, incentivized in police departments?”

Charles Ramsey, the former Philadelphia police commissioner who co-chaired President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, said officers need to see themselves through the eyes of those being policed. At times, Ramsey was criticized by the rank and file for being too harsh in disciplining officers. He believes it’s important for officers to understand how police have been used to implement racist policies, such as Jim Crow laws.

Negative encounters with police, many current Black officers say, pushed them toward a law enforcement career.

As a teenager, Horace Boatwright was walking home from a baseball game in South Carolina when an officer stopped him.

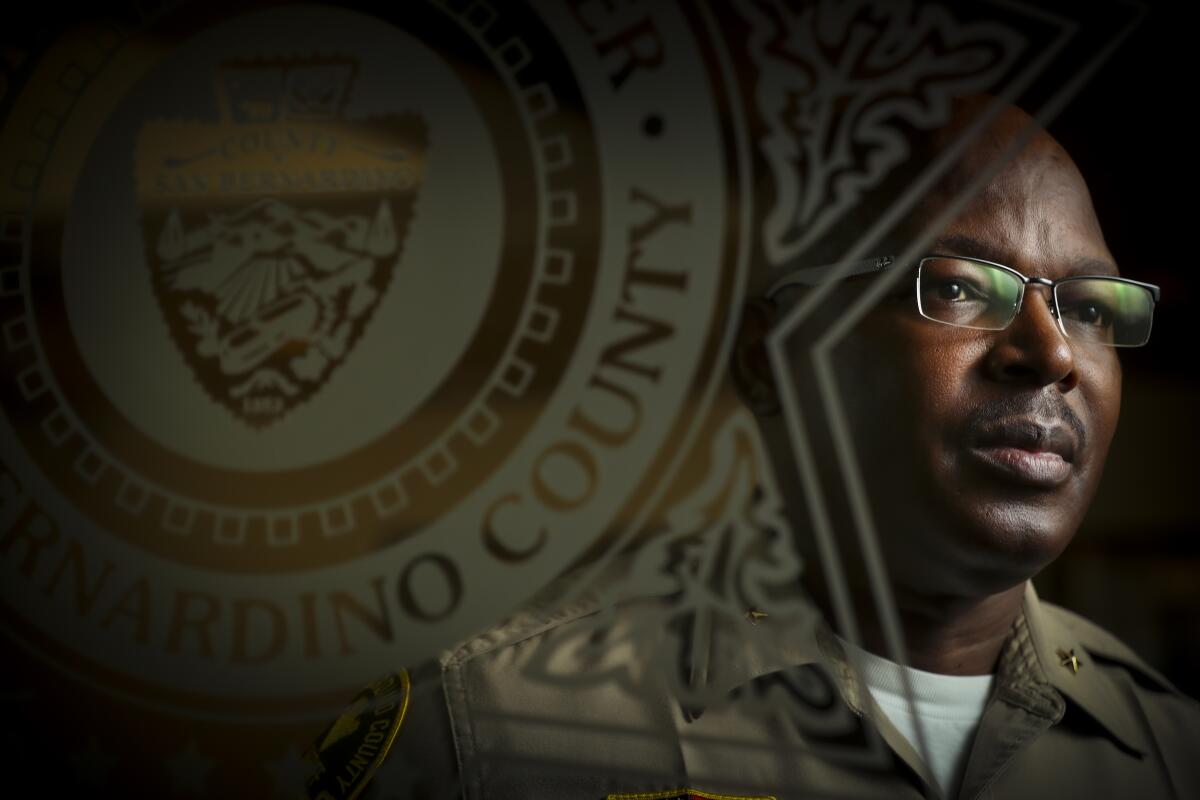

“He says if he caught me out at night again I would not make it home,” said Boatwright, now deputy chief of the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department. “I instantly became fearful of law enforcement.”

He joined the career to “do my part in modeling what a police officer should be — that’s ethical, accountable and compassionate to the needs of the community.”

Officers involved in misconduct should be held accountable criminally or administratively, he said, and rules should require their colleagues to intervene if they witness unethical conduct and to report bad behavior. Boatwright also said it’s important for his colleagues in the department to understand why Black people might be apprehensive or respond negatively during interactions with police. He’s been taking on those conversations.

“I try to let them know that although that person may have a perception, that perception is a reality, that feeling is real,” Boatwright said.

For Black police officers, forging relationships in their own community requires delicate navigation. Some say they have been called a race traitor, sellout or Uncle Tom while in uniform.

“When I receive that myself, being a Black man, yeah, the first thing that comes to mind, I’m hurt. But then I try to understand where they are coming from,” Boatwright said, adding that it never made him rethink his career choice. “I still think there’s a job I can do.”

San Bernardino County Deputy Frank Harris was recently assigned to a Rancho Cucamonga protest of about 300 people that turned disruptive, with people in the crowd throwing items at cars and jumping on a school bus, he said in an interview with the Sheriff’s Employees’ Benefit Assn.

At one point, at least two people started hurling racist insults at him, including the N-word. Video captured the encounter.

In the moment, Harris said, he wasn’t fazed because he fields insults like that all the time. It wasn’t until after the fact, when he watched the video, that it hit him.

“It really just made me sad,” he said in the interview, adding that he chose law enforcement because he saw a lack of diversity. “I kinda wanted to be out there in law enforcement to, you know, be, you know, a voice or a helping hand to, you know, young Black males.”

Those types of slurs hit Matt Burson the hardest early in his career.

“I got frustrated to a point where I’m like, ‘Why am I doing this?’” said Burson, chief of the professional standards division at the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department. “But then you look around at some of the violence and some of the things that people were experiencing at the time: Yeah, I know exactly why I’m doing this. I just got to remain focused on that.”

In 1979, Burson was a teenager walking home in South L.A. when he heard gunshots. He said the whole neighborhood swarmed to the scene, where two officers had shot and killed a Black woman, Eula Love, the mother of a girl Burson’s brother was dating at the time, over a gas bill. News accounts say she had a knife and that the Police Commission later concluded the officers made “serious errors in judgment.”

“I’ll tell you, I hated the police,” Burson said. “I hated LAPD and everything they stood for.”

A few years later, he began working as a retail loss prevention officer, which required regular interaction with officers. His brother had joined the California Highway Patrol. His feelings evolved.

“Over the years, you learn to either be part of the solution or nothing,” Burson said.

Scott, a former LAPD deputy chief, also had a negative encounter with police in college.

Scott said he was driving back to school at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa when he was stopped by an officer.

“The first thing that came out of his mouth was: ‘Boy,’” Scott said. “In the South, when you were called a boy, it meant like you were less than a man, less than them.”

Scott didn’t consider law enforcement as a career until a cousin who worked for the LAPD told him that Black officers “can do good things.” Soon after, Scott joined the department.

After 27 years, Scott was tapped in 2017 to lead the San Francisco Police Department, which had been plagued by scandal, including allegations of racist texting by officers. The U.S. Department of Justice found that the department disproportionately used force on people of color and stopped and searched Black people at higher rates than other ethnic groups.

Since then, San Francisco has banned chokeholds and strangleholds and officers are required to attempt to de-escalate tense situations and to file a report whenever they point a firearm at civilians. Last month, the department also stopped releasing mug shots of people who have been arrested unless the person poses a risk to the public.

There hasn’t been a police-involved shooting in the department in two years, and there’s been a 60% decrease in the use of firearms by officers, Scott said.

“Good policy when enforced properly ... does drive culture,” he said.

Los Angeles Police Cmdr. Gerald Woodyard said when he joined the department, he looked up other Black men in positions of leadership. His own journey into policing began when he was stopped by an LAPD officer in Inglewood years ago.

The officer said he smelled marijuana coming from the car, and Woodyard and a friend — both in suits and on their way to church — were searched. Instead of becoming angry, Woodyard decided to join the LAPD.

As a leader, he tries to recruit more Black officers. Of nearly 10,000 sworn officers, about 9%, or 951, are Black and the department expects many to retire soon.

“I’d rather the community sees folks that look like them and maybe they can relate to us and not be afraid of us,” he said.

Woodyard, who took a knee in solidarity with protesters, said the recent demonstrations have opened opportunities for “uncomfortable and authentic” conversations with the community.

“It has forced us as an organization to really look at how we police certain communities,” he said.

Orange County Sheriff’s Lt. Joses Walehwa, whose family immigrated to the U.S. from Uganda when he was a toddler, said friends and relatives have participated in protests. He spoke with one at length on the phone and told him that no one he knows in law enforcement can justify what happened to Floyd, who died after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for an extended period as he pleaded for air.

“This is a rare unique situation where everyone agrees … it shouldn’t have happened,” Walehwa said. “That was probably the biggest thing I could share with him.”

“At the end of the conversation, I was happy to say that this person said, ‘I’m proud of you, I’m proud for how you’re representing what you do,’” he said.

At protests where he is in uniform, Walehwa said, some interactions have been marked by anger and frustration, but as days went on there was productive dialogue.

“It wasn’t an ‘us-versus-them’ thing, it was, ‘Let’s give everybody space to speak.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.