‘Herstory’ is out as California revamps K-12 ethnic studies course guide

State officials unveiled their latest try at an ethnic studies curriculum for K-12 students Friday, and it’s clear their hope is that this time fewer people will be offended.

To appease critics of academic jargon, the new draft ditches terms such as “herstory” for the more traditional “history.” To better honor diversity, teachers are encouraged to let the ethnic composition of the class influence study topics.

Still, the new version retains a focus on the four groups long associated with ethnic studies: African Americans, Asian Americans, Chicanos/Latinos and Native American and Indigenous peoples. That aspect could reassure leaders in the field of ethnic studies, who shaped the first version but had less influence over the revision.

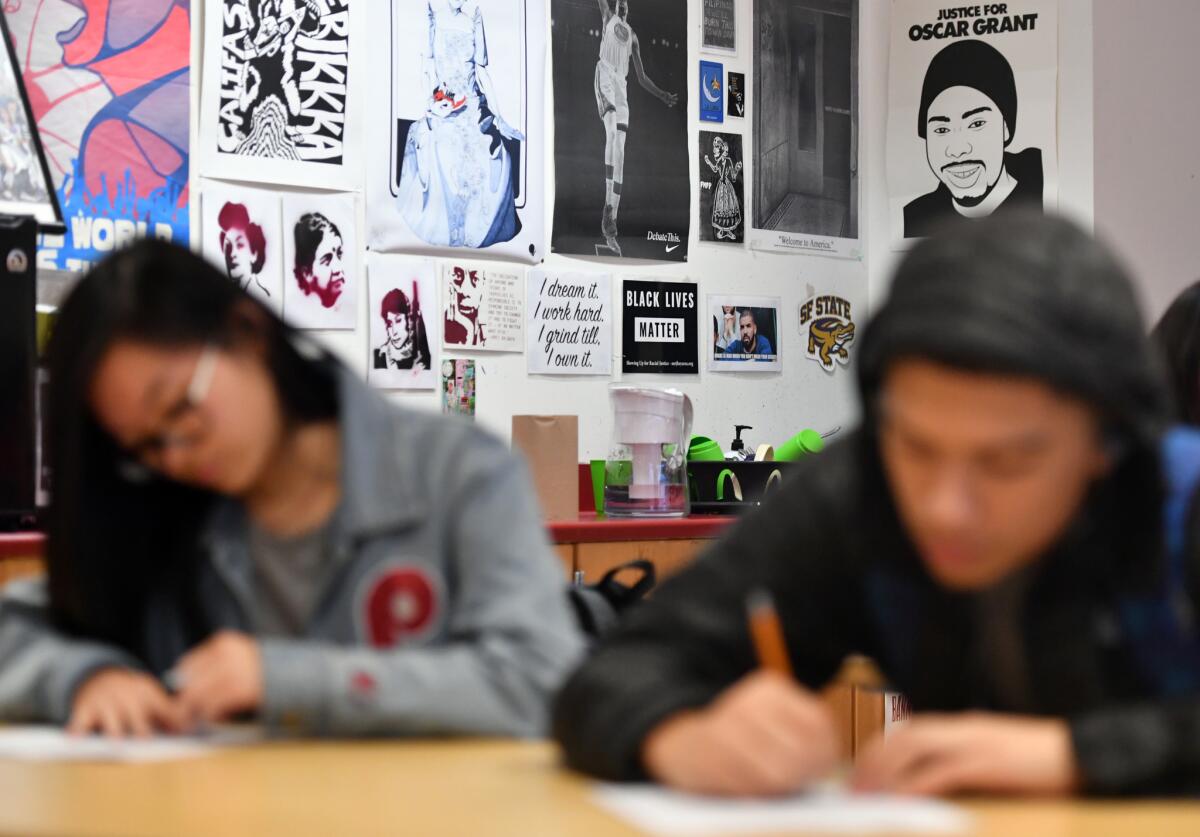

All told, the latest draft represents an attempt at compromise among strong, difficult-to-resolve passions. Ethnic studies is innately and even intentionally political in challenging established norms. All the same, it embodies widely supported goals that include empowering students of color, nurturing empathy among white students and developing critical thinking and historical perspective among all.

The push for ethnic studies in California has recently gained momentum, buoyed by Black Lives Matter protests that followed the May killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody. Ethnic studies, supporters say, has the potential to dismantle systemic and unconscious racism through the education of the citizens of tomorrow.

“Our schools have not always been a place where students can gain a full understanding of the contributions of people of color and the many ways throughout history — and present day — that our country has exploited, marginalized, and oppressed them,” state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said in a statement Friday. “At a time when people across the nation are calling for a fairer, more just society, we must empower and equip students and educators to have these courageous conversations in the classroom.”

Expect the reviews — positive and negative — to trickle in for weeks.

The debate is not merely for academics. This model curriculum is expected to guide teaching in K-12 public schools across California. The state Board of Education is scheduled to approve a final version by the end of March. And pending legislation would make ethnic studies a high school graduation requirement.

The latest version attempts to tone down references that some regarded as overly political or ideologically one-sided. There had been particular criticism of elements seen as anti-Semitic or anti-Israel, although there were Jews on both sides of the debate.

Among those with reservations about the original curriculum were members of the California Legislative Jewish Caucus, which had contended that the guide intentionally excluded Jews. The lawmakers faulted the first version for failing to explain anti-Semitism while providing an overly positive representation of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel.

“There were 14 forms of bigotry and racism in the glossary,” said Assemblyman Jesse Gabriel (D-Encino), who called the exclusion of anti-Semitism glaring, obvious and offensive.

Anti-Semitism is now noted more clearly in the curriculum as a form of bigotry.

Critics are not entirely satisfied.

The draft has improved, but not enough, said Sarah Levin, executive director of Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa.

“These supplemental materials ignore the stories of all our coalition members — who together represent an estimated 60% of Californians who hail from the Middle East and North Africa — while portraying the Arab American experience as a monolith to represent the region,” she said.

Another critic, Williamson Evers, also felt the improvement was inadequate.

“The proposed model curriculum is still full of left-wing ideological propaganda and indoctrination,” said Evers, a senior fellow at the Independent Institute, an Oakland think tank. “It still force feeds our children the socialist dogma that capitalism is oppression. It’s almost all Berkeley and little Bakersfield.”

The new draft arrived nearly a year after the California Department of Education shelved the original.

Officials arrived at the latest iteration after reviewing thousands of public comments, convening experts and conducting teacher focus groups.

At its core, supporters say, ethnic studies teaches students how to think critically about the world around them, “tell their own stories,” develop “a deep appreciation for cultural diversity and inclusion” and engage “socially and politically” to eradicate bigotry, hate and racism, according to the earlier draft of the model curriculum.

The model curriculum is meant to serve as a guideline rather than a mandate for schools that choose to offer ethnic studies classes. In California, as nationwide, these courses are increasing in number, with grade-school enrollment nearly doubling from 8,678 in 2013-14 to 17,354 in 2016-17, according to the state Department of Education.

There appears to be broad legislative support for making ethnic studies a high school graduation requirement. Some school systems already have taken that step.

Supporters of the original curriculum include 25,000 people who have signed a “Defend Ethnic Studies” petition, ethnic studies faculty from the California State University and University of California, and many Jewish groups.

R. Tolteka Cuauhtin, a Los Angeles teacher and co-chair of the advisory committee that created the original draft curriculum, said ethnic studies courses can be responsive to all students in a class and integrate other ethnic groups “without de-centering communities of color.”

Cuauhtin said ethnic studies terminology should remain in the curriculum. “Students of color need to also be respected as young intellectuals and given access to academic concepts and disciplinary language,” he said. “Every academic field has its own language, and yes, so does ethnic studies — let’s uplift that and ensure it’s accessible, not erase it.”

“Herstory,” for example, is a term used to describe history written from a feminist or women’s perspective. The term is also deployed when referring to counter-narratives within history.

Assemblyman Jose Medina, the author of the bill that would mandate ethnic studies, is optimistic about how the final product will turn out.

“The model curriculum is still a draft and in the early stages of the input process,” said Medina (D-Riverside). “I trust this process and believe we will end up with a strong ethnic studies framework that will provide a solid structure for educators to build off as they bring ethnic studies to life in their classrooms.”

In a related development, last month the Cal State Board of Trustees revised its general education curriculum for the first time in 40 years to create an ethnic studies and social justice requirement of all undergraduate students.

Ethnic studies faculty and some trustees criticized the requirement as being too broad and diluting the mission of ethnic studies, advocating instead for a narrower requirement proposed in a bill that is currently making its way to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.