Hollywood-backed activist endangered pets by treating them with his own products, veterinarians say

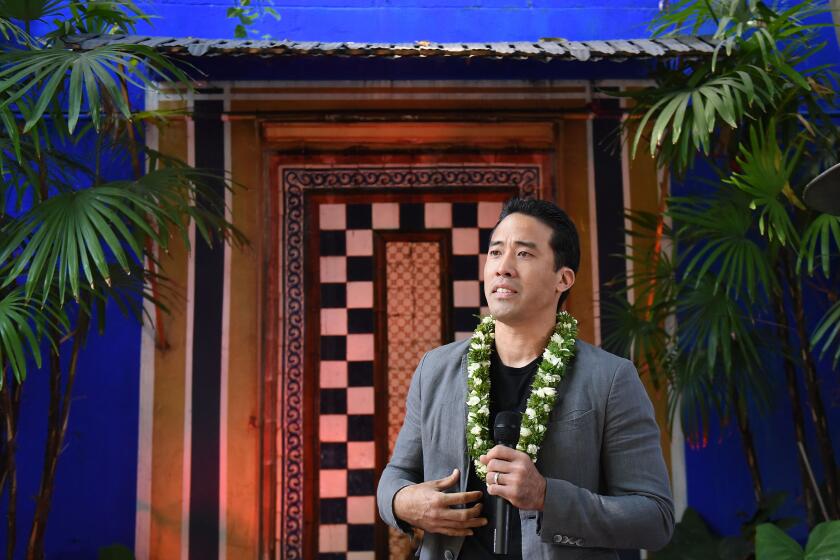

The accounts of the veterinarians echo each other and stretch back as long as seven years: Marc Ching, founder of a Hollywood-backed animal rescue charity, persuaded their clients to abandon a prescribed treatment regimen and instead give their ailing dogs and cats products he sells at his for-profit pet food store in Sherman Oaks.

More than a dozen Los Angeles-area veterinarians and others who care for animals told The Times that Ching’s actions threatened to harm — and in several cases did harm — pets they were treating for conditions such as kidney disease, heart failure and cancer.

Five of the care providers said they complained about Ching to the California Veterinary Medical Board, alleging he was practicing veterinary medicine at his store without a license. Ching, who describes himself as a fourth-generation herbalist and nutritionist, is not a veterinarian. The vets said the board either immediately rebuffed them or took no action.

Emilie Chaplow, a Studio City veterinarian, said she complained to the board after a client told her that Ching recommended giving a diabetic dog a steroid medication that could have killed the animal.

“It was 100% wrong,” Chaplow said. “I tell people if they use him, I will not see them as clients because he is so dangerous.”

Natalia Soto, a veterinary surgeon who works with Chaplow, said two years ago she was treating a dog that needed surgery to remove bladder stones. She said the dog’s owner told her Ching had advised that the stones would dissolve if she gave the pet his supplements.

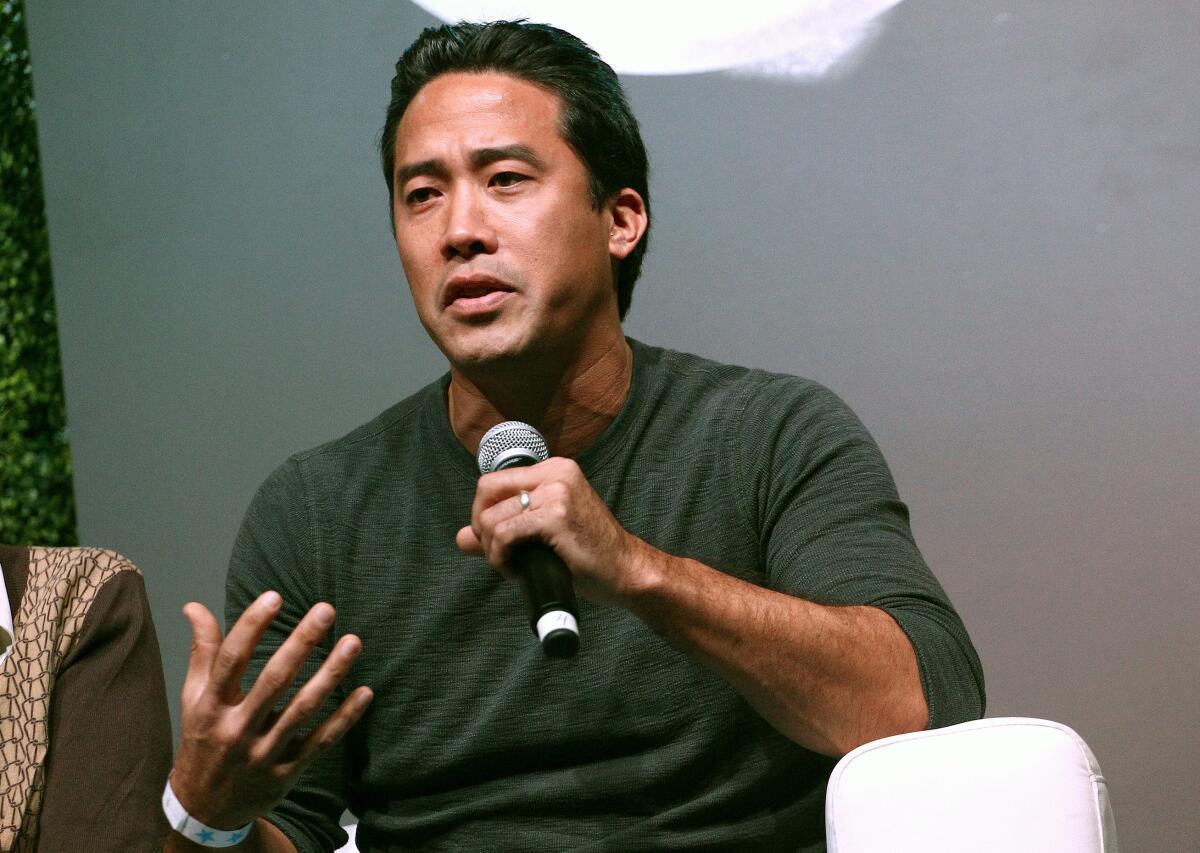

Activist Marc Ching, whose work won support from Joaquin Phoenix, Matt Damon and other celebrities, denies paying butchers in Asia to harm dogs.

Soto, who was an occasional volunteer with Ching’s foundation, said she persuaded the woman to return the supplements and authorize the surgery.

“I’m like, ‘These stones are not dissolvable,’” she recounted. “‘If they are dissolvable, the person to find that out would be a millionaire.’”

Soto’s client confirmed the vet’s account.

Ching did not respond to emailed questions from The Times for this article.

The California Veterinary Medical Board, which licenses vets and investigates complaints against them, has never taken any action against Ching, a board spokeswoman said. She said the board’s complaints and investigations are confidential.

In response to a Times inquiry, the California Department of Public Health recently launched an investigation of a 2018 complaint that Ching was selling pet food without the proper labels required by law.

Ching, an ex-convict who transformed himself into one of the most prominent leaders in the animal rights community here and abroad, was the subject of a Times investigation in May that found evidence contradicting claims he made about his efforts to rescue dogs and cats from Asian meat markets and the authenticity of some of the gruesome videos he shot of animals being tortured and killed.

The investigation also raised questions about the financial practices and fundraising methods of his charity, the Animal Hope and Wellness Foundation, which has collected millions of dollars in donations with the help of celebrities such as Joaquin Phoenix, Bill Maher and Whitney Cummings.

In an earlier interview and in emailed statements, Ching and his attorneys said he has always been truthful about his work overseas, the videos were genuine and he never misused foundation funds or harmed animals.

In April, the Federal Trade Commission accused Ching of making false or deceptive claims that an herbal supplement he was selling could treat COVID-19 and that some of his other products could treat cancer. Ching denied doing anything wrong. Earlier this month, he agreed to a settlement in which he is barred from making baseless claims that his products can treat COVID-19 or cancer.

The veterinarians’ allegations center on what clients told them about their encounters with Ching at the Petstaurant, his boutique food and supplement store in Sherman Oaks. (Ching recently opened a second Petstaurant on the Westside.)

The doctors said they are open to alternative approaches to treatment, but not if they are therapeutically unsound and pushed by someone without the required training. That’s where Ching crosses the line, the veterinarians said.

They said some of their clients referred to Ching as “Dr. Ching” or “Dr. Marc,” in the belief he is a veterinarian.

The homepage of the Petstaurant website promotes its products as providing “the best in health care” for skin and food allergies, arthritis, ear infections and other ailments.

Peter Weinstein, a veterinarian who is executive director of the Southern California Veterinary Medicine Assn., a professional organization, said he mailed a complaint about Ching to the California Veterinary Medical Board in 2014. The complaint said some content on the Petstaurant website “could be considered to be offering a diagnosis and suggested treatment.”

A whistleblower and watchdogs raise concerns over cash withdrawals, allegedly deceptive solicitations and other financial practices at the Animal Hope & Wellness Foundation. The charity denies misleading donors or misusing money.

Weinstein said he received “the typical response — ‘we’ll take it under advisement,’” and never heard from the board again.

Mark Nunez, a West Hollywood veterinarian who has served on the California Veterinary Medical Board since 2013, said several of his clients whose dogs had skin disorders had turned to Ching for help. According to Nunez, Ching put the dogs on a diet of his food and said it would eliminate the maladies. Nunez said the dogs did not improve and the owners came to him in frustration.

“It’s misleading to a consumer who is assuming that Marc Ching has medical knowledge that he really doesn’t,” Nunez said. “That’s a period of time that a pet is needlessly suffering.”

Nunez added that he encouraged three or four veterinarians who called him with complaints about Ching to report their concerns to the board. He never filed a complaint himself and did not know whether board staff had investigated any formal complaints about Ching. None of them ever reached him at the board level, he said.

The board employs four staff members to conduct investigations of complaints. If an investigation determines that someone who is unlicensed violated California’s veterinarian laws, the board’s executive officer has the authority to issue citations that can include a fine and an order to cease and desist. The agency also has the authority to refer complaints to county district attorneys for possible prosecution, a board spokeswoman said in an email to The Times.

“At this time, the board has not issued any citations or fines against Marc Ching,” she said. “You may wish to check back with the board at a later date to inquire whether any citation or fine has been issued.”

Several veterinarians who spoke to The Times asked that their names not be published because they feared retaliation by Ching, whose foundation has sued two former volunteers for the charity and its former executive director after they criticized him.

The foundation’s tax returns show that the Petstaurant has sold at least $59,000 in food and supplements to the charity. The California attorney general’s office has notified the foundation that it was conducting an audit of the charity’s books.

One doctor who requested anonymity said she complained to the board after an encounter with Ching in West L.A. The board-certified internal medicine specialist was treating a dog for acute liver failure. The dog was discharged and the owner continued oral treatment at home.

A few days later at a checkup, the owner told her that Ching recommended stopping the medication and feeding the dog a Petstaurant diet. The doctor advised that Ching’s course of action was inappropriate and asked to speak to Ching.

The doctor said her client called Ching and handed the phone to her. She said Ching initially told her he was a veterinary nutritionist. After the doctor questioned him on his training and experience, he admitted he was not and said he was actually a human nutritionist, she said.

“I tell all the interns, residents, new doctors I know not to trust him or his advice,” the doctor said of Ching.

The doctor said that when she called the board and complained that Ching was impersonating a veterinarian, a representative told her the agency “couldn’t do anything” because she had no written proof to support her complaint.

Marc Ching, a prominent Southern California animal rights advocate, has agreed to stop pitching an herbal supplement as a remedy for COVID-19.

The board spokeswoman said written material is not required to initiate an investigation. She said “all complaints are taken seriously” but the most effective ones “contain firsthand verifiable information.”

A second veterinarian who asked not to be identified said she was treating a dog for lymphoma about a year and a half ago when Ching urged the owners to abandon the prescribed chemotherapy and steroids in favor of his supplements.

“One was liquid and it didn’t even have a list of ingredients,” the veterinarian said.

She said she persuaded the owner to stay with her course of treatment and stop giving the dog the supplements. The dog lived longer than average for a lymphoma patient, the doctor said.

She said Ching more recently told a second client to place a cat with kidney disease on a high-protein diet, which could have killed the animal. The veterinarian said the client heeded her warning not to do so and the cat survived.

Another veterinarian who spoke on condition she not be named said she sent a complaint to the veterinary board in 2013, alleging that Ching was “harming animal health ... as well as defrauding consumers with false and misleading claims.” She said she did not recall receiving any response from the board.

The veterinarian said one of her clients allowed Ching to put her dog on a Petstaurant diet. The dog became emaciated and “was at death’s door,” the veterinarian said. She said she persuaded her client to place the dog on a normal diet and it recovered.

Two veterinarians who also requested anonymity said their clients followed Ching’s advice to take dogs off medications for heart disease and replace them with a Petstaurant diet and supplements. One of the doctors said, “The dog came back to me coughing uncontrollably and in heart failure. I hospitalized the dog that day. My client was shocked.”

The other veterinarian said her client’s dog had a damaged heart valve. After a week or so on Ching’s supplements, “the dog had increased panting, more respiratory effort,” she said. She said she told her client, “‘Why would you ever listen to someone who sells food?’ She put him back on the medication and the dog was fine.”

A veterinarian who also asked not to be named said she hears from clients about Ching every couple of weeks, often involving cases in which he persuades them to take their dogs off prescribed flea medications and put them on his diets.

“One dog got sick from a flea-borne disease,” recalled the veterinarian, who said she treated the animal about two years ago.

The veterinarian said Ching also gave one of her clients a letter he wrote in email form exempting a dog from a rabies vaccine. (The Times has reviewed the letter.) She said such exemptions are rarely requested by veterinarians and generally only in cases in which the vaccine could kill the dog. The exemptions are used by pet owners when they don’t have a vaccine certification required by kennels or groomers.

Ching wrote the letter “as if he were a veterinarian,” the doctor said. She said it was “blatantly illegal and a human health risk.”

Laurel Kinder is not a veterinarian, but she runs a low-cost pet clinic in North Hollywood where Ching brought rescue dogs for treatment. She said a clinic veterinarian advised Ching to take a dog with a blood disorder to a specialist for medication. Instead, Kinder said, Ching allowed a woman to adopt the dog and told her to give it iron supplements.

The woman later brought the dog back to the clinic for a teeth cleaning under anesthesia, still suffering from the disorder, Kinder said.

“If I had put that dog under, it would have died,” she said.

The veterinarian who complained to the state Department of Public Health in 2018 about the labeling of some of the Petstaurant food also asked not to be named. The labels lacked information required by law, the veterinarian said.

In the emailed complaint, which The Times reviewed, she said the Petstaurant sold her client the food to treat allergies. The veterinarian said she had to send several emails to receive any response from the department and it ultimately failed to follow up with her.

A department spokesman said the agency hadn’t acted on the doctor’s allegations because “there was a delay due to improper entry” in the complaint system but had recently reached out to the veterinarian.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.