In L.A. race, is this incumbent a ‘progressive fighter’ or a knockoff?

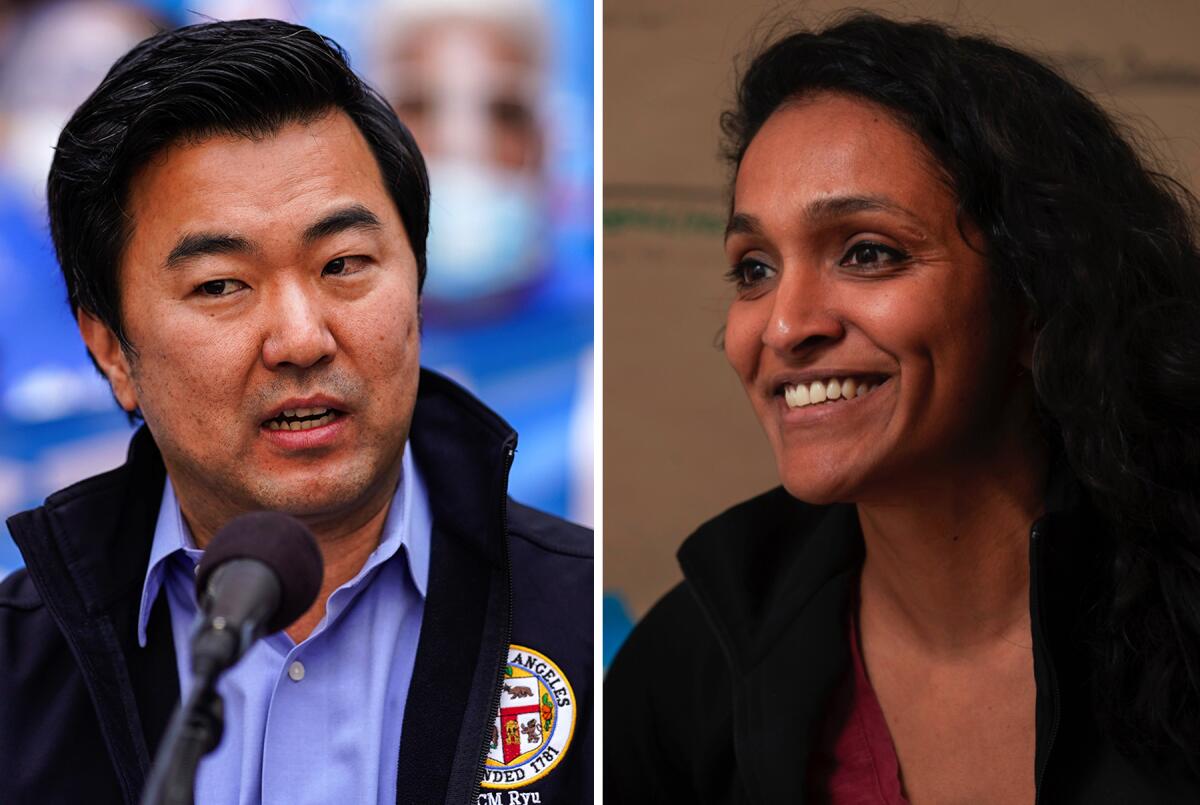

When L.A. City Council candidate Nithya Raman pledged not to accept any political donations from police unions, she tweeted a photo of herself, head bowed, signing the document.

Hours later, Councilman David Ryu tweeted that he too was signing the “No Cop Money” pledge and shared a similar photo, triggering accusations that he was copying his progressive challenger.

The Ryu campaign called those claims a “misrepresentation,” pointing out that the pledge gave clear instructions on how to take a photo and tweet it. The councilman and his supporters argue Ryu has always been a progressive.

“The political climate has shifted — I haven’t,” Ryu said, calling himself a “progressive fighter.”

But as Ryu fights to keep his seat against Raman, he is clearly running a different campaign than five years ago or even five months ago, when L.A.’s police union shelled out nearly $45,000 in independent spending to support him.

The race reflects the changing dynamics of L.A. elections: Local contests now come at the same time as national races that tend to draw a more left-leaning crowd to the polls. On top of that, the eruption of protests against police brutality has spurred a national reckoning over racism and police power.

The result is that a council district that stretches from Sherman Oaks to the Miracle Mile and includes wealthy, majority-white neighborhoods like Hancock Park and the Hollywood Hills is now seeing a progressive showdown over issues such as protecting tenants and reimagining policing.

Activist groups such as Ground Game LA hope to harness those currents to elect Raman, an urban planner who headed the Time’s Up Entertainment campaign against sexual misconduct and led a Silver Lake homeless outreach group. Raman has advocated for a network of community access centers to assist unhoused people and opposed laws that “criminalize” homelessness, including broad restrictions on where people can sleep in their cars.

“We live in a city where almost every politician calls themselves a progressive,” yet “you often see a disconnect” with the policies emerging from City Hall, Raman said. In March, she forced Ryu into a November runoff by winning 41% of the vote to his nearly 45% — a feat that was even more remarkable because Ryu outspent her by more than 3 to 1.

The protesters have been on the streets of downtown Los Angeles for more than 40 days. On Tuesday, their typically peaceful protest became violent. And that’s where the stories diverge.

When Ryu first won the council seat, the race was dominated by concerns about out-of-scale development.

His victory stunned many because Ryu was a City Hall outsider — a former aide to a county supervisor who worked for a South L.A. psychiatric hospital and community health center — pitted against a former council staffer backed by city leaders.

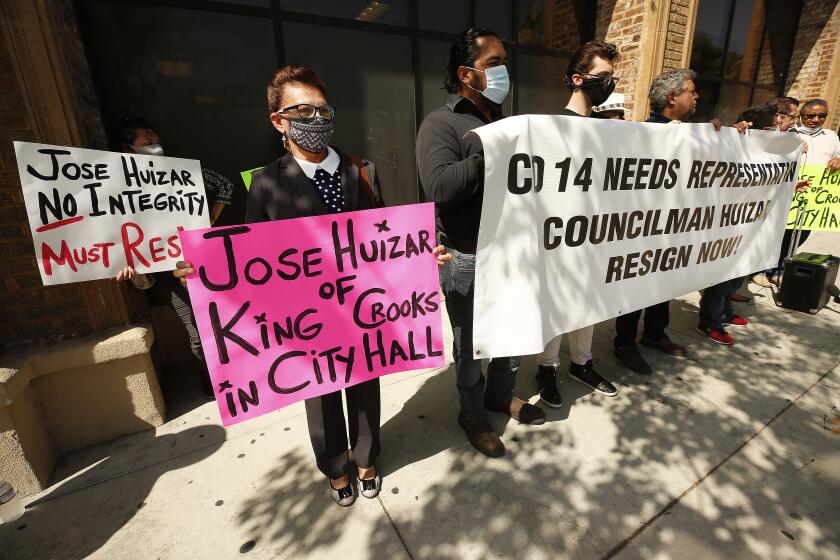

His public push against campaign donations from real estate developers also set him apart on the council. No one bit on his initial bid to bar donations from corporations and other groups, and the idea of limiting developer money gained little traction until after the FBI descended on City Hall.

As homelessness surged to the forefront, Ryu touted new housing and shelters he had approved for homeless residents, but Raman argued the city could be doing much more. Critics also pointed out that Ryu voted to reinstate restrictions on sleeping in cars and had initially forwarded a plan to limit sidewalk sleeping, which he later opposed.

Attorney and former city commissioner William Funderburk, who supports Ryu, argued that the councilman is uniquely qualified to tackle issues of homelessness and disadvantage because of his earlier work in social services and mental health, saying that he “has always been the person who takes on the powerful and the privileged.”

“The close race has given him an opportunity to define who he really is — the person who fights for the underdog,” Funderburk said.

Since the March election, Ryu has gotten a new campaign manager, replaced his consultant and overhauled his campaign website, which is now full of photos of Ryu at protests and frames him as an activist fighting for systemic change.

This spring, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Ryu backed a blanket ban on evictions that failed to win council approval. He succeeded in pushing through new restrictions on ejecting belongings from storage units and a rent freeze in units covered by the Rent Stabilization Ordinance, which limits annual hikes.

Not everyone is impressed.

“He’s chasing whatever he thinks is politically expedient,” said Danielle Cendejas, a political consultant who previously worked with Sarah Kate Levy, another candidate who challenged Ryu in the primary.

Cendejas questioned whether it would win him support. Ryu has lost at least one group since the primary: A political action committee tied to the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce yanked its earlier endorsement of Ryu, saying his actions at City Hall had “led to an unfair burden on Los Angeles businesses.”

Some Raman supporters accuse Ryu of running a knockoff campaign. Ryu came out in support of expanding the council to better represent Angelenos; Raman had included that idea in her platform, arguing it would reduce the concentration of power. Raman championed a rent freeze ahead of the March election; Ryu introduced it during the pandemic.

During a videoconference meeting for campaign volunteers, Raman argued that “it shouldn’t take a global pandemic to put real eviction protections in place, to put a rent freeze into place in a city that has had tens of thousands of evictions annually.”

She wants the city to go further and pursue a “rent forgiveness” policy with tax credits for big landlords amid the crisis.

Ryu is “trying to get on board with a lot of this and I respect that,” said Suju Vijayan, a Sherman Oaks resident volunteering on the Raman campaign. But Raman “is not following but leading in those areas.”

Others reject the idea that Ryu has changed his focus to compete with Raman. Tenant advocate and city commissioner Larry Gross said “the guy has been there for tenants before and throughout,” pointing to his steady opposition to turning a Hollywood apartment building into a hotel and recent letters telling landlords to “back off” on improper demands.

Los Feliz resident J.P. Lavin said Ryu helped him and other tenants when a landlord was trying to eject them from their building. “He could have easily taken the side of business.... To me, that’s as progressive as you can get,” Lavin said.

Gross said Ryu may not have proposed a rent freeze before the pandemic, but “I don’t think there would have been the votes there for that” at the time. Ryu also said he had long been interested in expanding the council and “tried to talk about this issue five years ago, but no one would even hear it.”

When Ryu pledged not to take political donations from police unions, critics pointed out he had already benefited from nearly $45,000 in independent spending by the Los Angeles Police Protective League during the primary. Raman supporter Mitra Jouhari said “it’s not impressive to me if you’re promising to not do something that you’ve already done.”

Federal prosecutors have alleged, without mentioning her by name, that L.A. Councilman Jose Huizar’s mother helped him launder bribe money.

Such independent spending cannot legally be controlled by candidates. The councilman argued that the money spent by the police union had not influenced him, pointing out that he voted to reduce the LAPD budget and sought a review of police tactics against protesters. His campaign said he had stated his opposition to boosting the LAPD budget in April.

But while Ryu had expressed concerns about cuts to city services, his representatives were unable to provide specific examples of Ryu saying in April that he opposed increasing the police budget.

Critics pointed out that in February, Ryu tweeted that he was “fighting for more officers for our local LAPD divisions.”

“This is a guy who really until last month had never spoken a word about police violence or racial injustice in the city of L.A. ... suddenly posting pictures of himself marching with Black activists,” said Hayes Davenport, who worked with Raman at her homeless outreach group and volunteers on her campaign.

Ryu countered that he has worked on issues of racial justice since the unrest of 1992 propelled him into a career in nonprofits and public service. Former county Supervisor Yvonne Brathwaite Burke said that as her aide, he was deeply involved in matters that disproportionately affected the Black community.

The councilman, in turn, questioned whether Raman had spoken much about police brutality ahead of the primary. Raman countered that she had repeatedly talked about police shootings — including the shooting of a homeless man, which she said underscored the need to fund other services besides police.

Times staff writers Ben Welsh and Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.