Coronavirus testing for half a million L.A. students each week? Easier said than done

Testing before schooling.

That’s the approach Supt. Austin Beutner called for this week when he said it might be unsafe to reopen Los Angeles Unified School District campuses until coronavirus testing is available to all K-12 students and employees on a regular, even weekly, basis.

That would mean enough tests for nearly half a million students and 75,000 staff members, in some 760 campuses from San Pedro to Chatsworth.

Such an undertaking would be unprecedented in scale, dwarfing the current testing levels in the county and straining a testing infrastructure that is already failing to keep up with surging demand. As recently as last week, county public health officials recommended narrowed testing criteria because of limited supplies and infrastructure.

The approach is stirring some criticism, including from President Trump, who said it was a “terrible decision” to keep schools closed.

Some experts, including those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, don’t recommend widespread testing at schools; others raise questions about the feasibility of creating such a program on short notice.

“I don’t think it’s really practical,” said Claire Garrido-Ortega, an epidemiology lecturer at Cal State Long Beach. “At this point, we need to reduce risk,” she said. “Testing doesn’t necessarily reduce risk.”

Others have endorsed Beutner’s decision to keep campuses closed for now, given the current spike in coronavirus cases. Some Harvard experts argue in a report that, due to false negatives and the rate of spread, every member of a population would have to be tested every three to four days to allow for reopening — an approach very much in line with Beutner’s proposal.

With the clamor growing from the Trump administration, and some parents, for children to return to the classroom, Beutner made clear that assuring the safety of students and staff in the nation’s second-largest school district would have to come first.

The decision reflects the concerns of many experts. Classrooms are perfect venues for widespread infection: Dozens of students are packed into a confined space, pulling their itchy face masks down to touch their noses and mouths. Children typically have more close contacts than adults, and many teachers are in older age groups, with preexisting conditions. When Israel reopened its schools, outbreaks followed.

In Arizona, three teachers who shared a classroom for virtual summer school all contracted the novel coronavirus. One of them died, reports said.

“Testing the few will protect the many,” said Beutner in his remarks on Monday. “The right way to reopen schools is to make sure there is a robust system of testing and contact tracing to mitigate the risk for all in the school community.”

The success seen by South Korea, Denmark, Germany and Vietnam in fighting the virus, he said, was due to robust contact tracing operations that could be applied to L.A. County schools. “In one of our high schools, for example, the almost 2,900 students and staff have frequent contact with another 100,000 people,” he said.

But the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention explicitly “does not recommend” comprehensive school-based testing, the agency noted in bold letters on its website, citing a lack of evidence that it would reduce transmission, plus concerns about resources, parental consent and student privacy.

To conduct weekly screenings, the school district would need to procure personal protective equipment, hire and train people to conduct the tests and adopt a secure system for record-keeping. The school district has about 485,000 students ranging from kindergartners to high school seniors, plus more than 75,000 full- and part-time employees. Weekly screenings would mean at least 80,000-110,000 tests per day, depending on whether some can be conducted during the weekend.

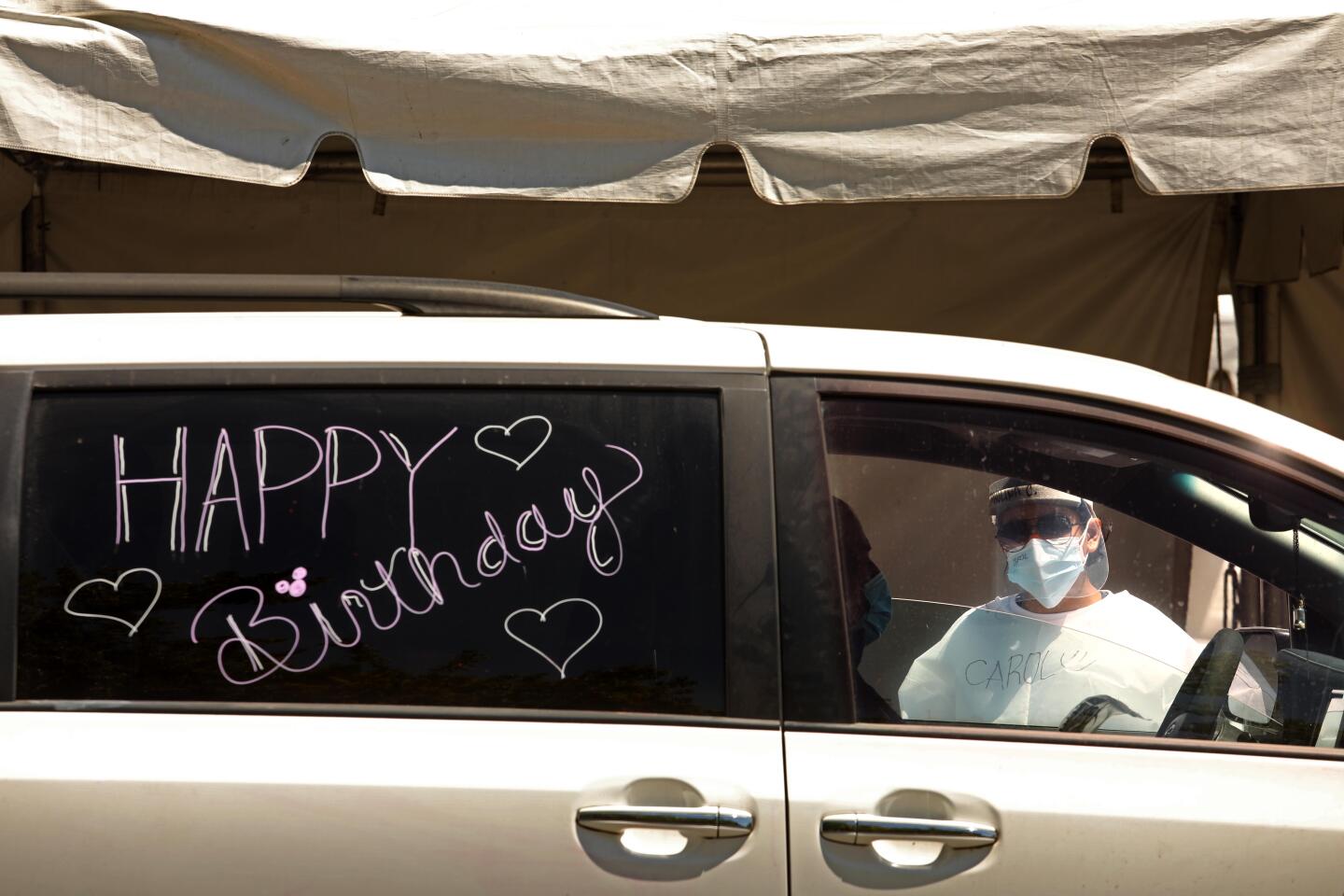

In L.A. County, simply launching a new testing location to serve 2,500 members of the public can take about two weeks, said Ann Lee, chief executive of Community Organized Relief Effort, which oversees testing at several locations across L.A., including Dodger Stadium.

Barbara Ferrer, director of the county’s public health department, said Germany was the only country she knew of that had instituted student testing for coronavirus. She had reservations about following Germany’s lead.

“A, this is a very large county, and B, there’s a limit to what testing will tell us,” she said, since it reflects a person’s infection status only at the moment of testing, and results can take several days. “As we learn more and have better testing capacity, it’s worth sort of revisiting what the role is of testing in the schools. But right now, I would urge us to really focus a lot on the infection control and the distancing protocols that we’ve put in place.”

Another key challenge to the school testing blueprint is a physical one: supply. In order to test all staff and students each week, the school district would need to obtain more than half a million swabs, tubes and units of reagents.

And any personal protective equipment obtained for health workers taking samples, or lab workers analyzing them, would presumably subtract from what is available to hospital staff on the front lines of the outbreak, critics said.

Already, Los Angeles County has experienced dwindling supplies for its public testing locations due to increased demand. Until earlier this month, officials encouraged all residents to get tested. But last week, officials suggested that priority be given to people who experience symptoms, have been in contact with someone who was exposed or work in a high-risk environment.

“The mismatch of demand has become more apparent,” L.A. County Health Services Director Dr. Christina Ghaly said last week, when the new recommendations were announced. “We have to watch the supply chain.”

It would cost about $300 per student over the course of a year to test students and staff weekly, along with family members of those who test positive, according to Beutner.

But scientists say such calculations are misleading. “This is not about money. It’s about physics,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “We are going to have a collision course with destiny.”

Testing capacity in L.A. County has greatly expanded since early in the pandemic. In the first week of April, about 30,000 people were tested for COVID-19 across clinics, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities and government-testing sites in the county. Two thirds of those tests were administered by city or county testing sites.

In the last week of June, 191,046 people were tested across L.A. County, 87,345 of them at government-run sites. There are nearly 100 testing sites throughout the county that are run by the city, county or their partners.

But L.A. County’s testing challenges abound, even without a school-based testing infrastructure. The county was one of the first to offer testing to asymptomatic people, yet residents have recently reported problems scheduling appointments. Many say there are no available slots despite checking multiple times. People experiencing symptoms still wait hours for testing, at drive-through lines that stretch for miles. They’ve reported waiting more than 10 days for results.

While the county has struggled with widespread contact tracing — identifying and getting in touch with people who may have come into contact with infected persons — Beutner said school systems are “much better placed” than other social infrastructures to do so, citing the preexisting relationships there. Families trust schools with their personal information, he said, and schools likely keep the most accurate, real-time data of any group.

There’s one thing experts can all agree on: If mishandled, reopening schools would affect exponentially more people than the students who attend.

“A 10-year-old student might have a 30-year-old teacher, a 50-year-old bus driver or live with a 70-year-old grandmother,” Beutner said Monday. “There’s a public health imperative to keep schools from becoming a petri dish.”

Staff writers Colleen Shalby and Howard Blume contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.