California is confronting its ugly, racist past. But how do we best do it?

Julie Tumamait-Stenslie scoffs when she hears defenders of the Father Junipero Serra statue in Ventura say it honors the city’s founder.

She is tribal chair of the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians (Chumash), whose ancestors lived for generations on the Channel Islands off the Santa Barbara-Ventura coast.

“There were cities on this land for thousands and thousands of years with social, political and religious customs,” Tumamait-Stenslie says. “Today you drive on our pathways, our trading networks. We’ve been in Ventura for thousands of years.”

And when Serra defenders say the 18th century Franciscan friar, who founded the California mission system during Spanish rule, protected and cared for Indigenous people, she replies:

“He did that because we were the free work force, the slave labor for the missions. Of course he was going to protect us. What else would he do? Go out and actually pay somebody to do the work? He had free slave labor.”

Native Americans who tried to escape the missions were tracked down and often beaten. Many died of disease spread by the European invaders.

“Ninety percent of our people were gone by the end of the mission period,” the tribal chair says. “They died.”

Historians basically agree with her depiction of mission life for Indians.

The late Kevin Starr, a state librarian and professor who produced several volumes on California history, wrote in his book “California” that the mission system was “a violent intrusion into the culture and human rights of Indigenous people….”

“They were being forced from their homelands, brought into the mission system — frequently against their will — and treated as children…. As children, they could be beaten when they proved recalcitrant or ran away from the mission, as they frequently did, and were recaptured….

“Many … died of shock at their displacement or of Spanish diseases. The sexual exploitation of Native American females by Spanish soldiers and other men in the colony was especially devastating as a matter of both personal violation and venereal disease.”

But there’s much more to blame for the genocide of California Indians than Serra, Spanish soldiers or Christopher Columbus, who began the decimation of Native Americans in 1492.

In 1851, California’s first elected governor, Peter Burnett, declared in his State of the State address: “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected.”

In the 1850s, the state Legislature appropriated $1.29 million to wage militia war against Native Americans. Some of that money was used to pay bounties for body parts — 25 cents per scalp, up to $5 for a whole head.

California’s indigenous population exceeded 200,000 in 1800 but plummeted to about 15,000 by 1900.

“It’s called genocide,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said last year at a ceremony with tribal leaders as he formally apologized for the state. “No other way to describe it, and that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books.”

California Indians always had a legitimate grievance against Serra, but their voices stayed relatively muted until Pope Francis elevated the friar to sainthood in 2015. Then the vandalism and toppling of statues began.

When the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis policeman set off nationwide “Black Lives Matter” protests against racism, it rekindled anger over the mistreatment of Native Americans.

Indigenous activists tore down a Serra statue in Father Serra Park in downtown Los Angeles. Protesters in San Francisco toppled a Serra statue in Golden Gate Park. Last weekend, demonstrators overturned a Serra statue in Sacramento’s Capitol Park.

And in Ventura, trying to protect the community’s Sierra statue from being spray-painted or ripped down, a coalition announced its intention to remove the monument from its prominent hillside location in front of City Hall overlooking downtown.

Tumamait-Stenslie, who lives in Ojai, says the statue symbolizes “the taking away of our livelihoods, our religion, our land — the genocide that changed us forever.”

“People say burn down the statue,” she continues, “but that’s not what we want. We don’t want it vandalized. We just want it removed from a public place.”

She, Ventura Mayor Matt LaVere and Father Tom Elewaut of the nearby Mission San Buenaventura, would like it to be transferred to the mission that Serra founded.

“The tribe, church and city have had positive discussions and we’ve asked the rest of the community to speak up and voice their opinion,” LaVere says. “You’ve got to include the community in decisions like this.”

Hear that, governor and legislative leaders. Unlike you, Ventura is doing it in a more inclusive way.

Prodded by Newsom, state Senate leader Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) and Assembly Rules Committee Chairman Ken Cooley (D-Rancho Cordova) issued a brief statement announcing that a 137-year-old statue of Columbus and Spanish Queen Isabella would be removed from its centerpiece position in the Capitol rotunda.

No public discussion by legislators, let alone the public.

“Christopher Columbus is a deeply polarizing historical figure given the deadly impact his arrival in this hemisphere had on indigenous populations,” the statement read. “The continued presence of this statue in California’s Capitol … is completely out of place today. It will be removed.”

Several Senate Republicans protested.

“If the statue is a problem, why can’t we have a conversation about it?” asks Senate GOP Caucus Chairman Brian Jones of Santee. “There should be a process for deciding these things.”

There is. Ventura is using it. A public discussion of removing such memorials might also allow for education about an ugly history that many still don’t fully understand.

“My family was brought to the San Fernando mission in 1799,” Tataviam/Chumash elder Alan Salazar told my colleague Carolina A. Miranda when he and others pulled down a Serra statue on Olvera Street. “So when I talk about Native people who lost their culture, their language and their lives — and were worked like slaves at the missions — I’m talking about my great-great-great-great-grandparents.”

Many of us are wrestling with this whole issue. For all the terror and misery Serra and Columbus brought, they are undeniably important figures in human history. One thing is clear: Society is now reappraising their legacies with clearer eyes, and we don’t like what we see.

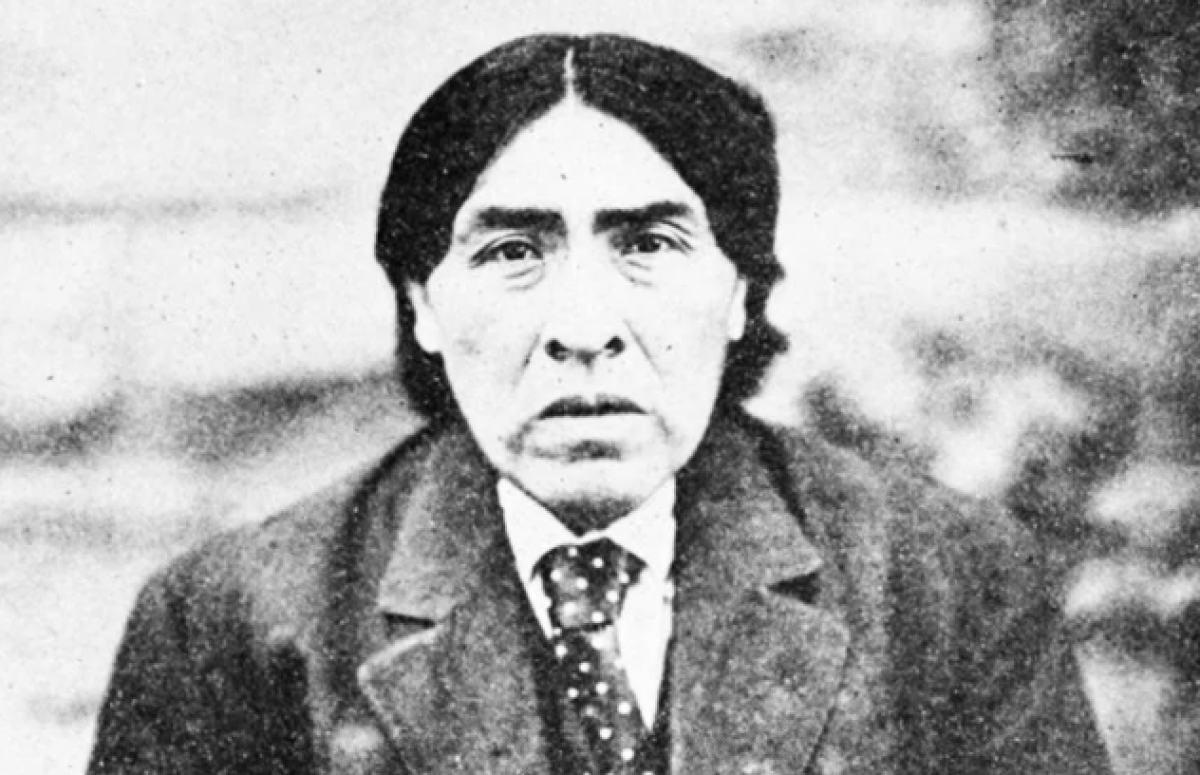

Here is one way of honoring California history: Their places of honor should be taken by important California Indians. My nomination: Ishi of the Yahi tribe, believed to be the last or one of the last surviving Native Americans to emerge from the California wild.

The Times has reported the Yahi “were virtually annihilated in a series of massacres described by anthropologists as the fiercest and most uncompromising resistance met by Indians on the West Coast.” In 1911, Ishi came out from hiding, assuming he too would be killed by the white man.

The University of California Anthropology Museum took him in, studying the Stone Age survivor, working him as a janitor and using him as a museum attraction as he chipped arrowheads and shaped bows. More recent reports document his mistreatment at Berkeley. He died in 1916 of tuberculosis.

Ishi should be sculpted and honored in California’s Capitol.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.