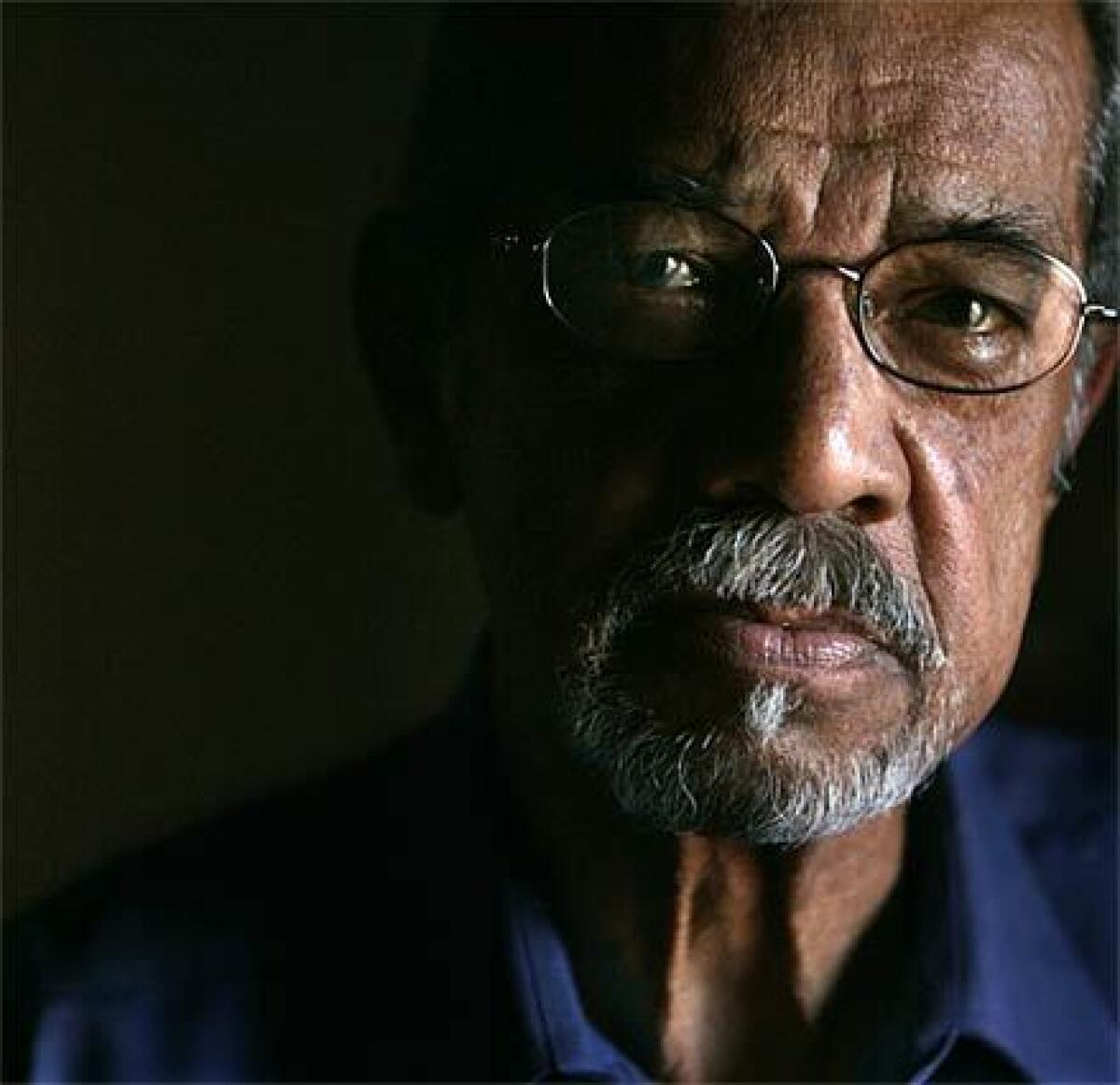

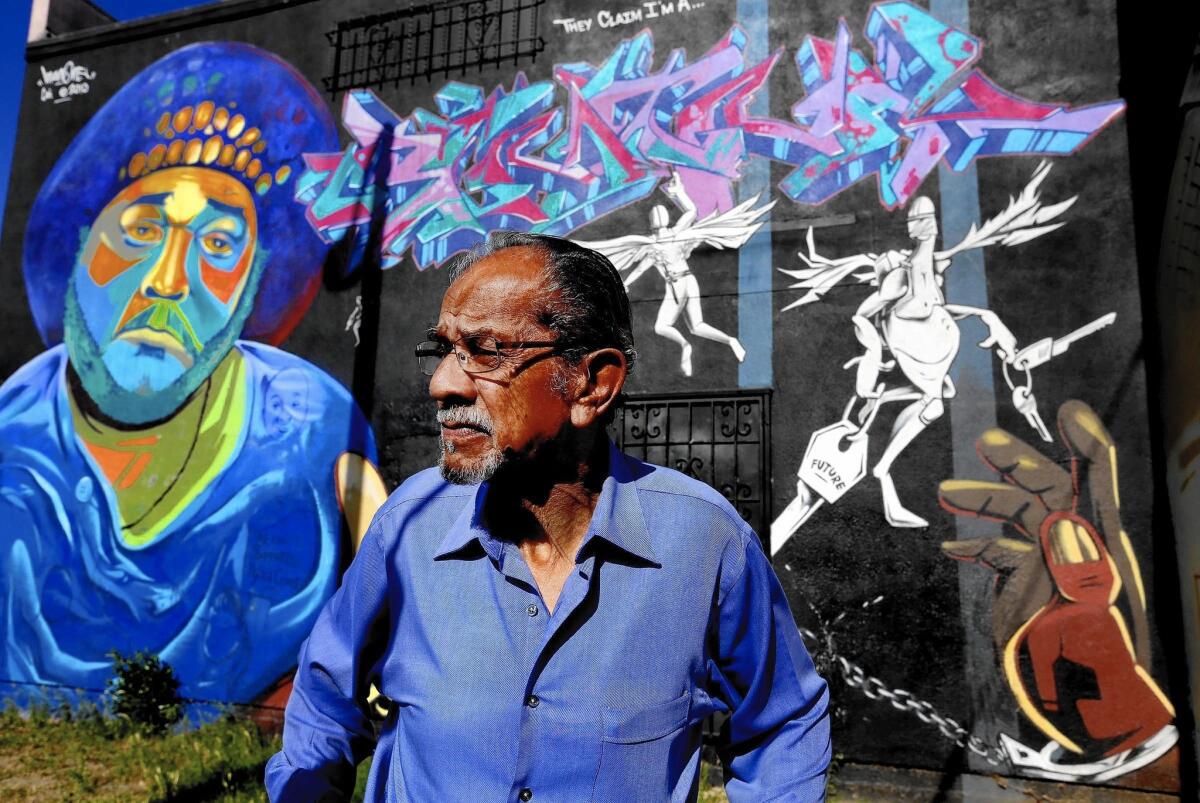

Larry Aubry, black activist icon and ‘godfather of South Central Los Angeles,’ dies

Larry Aubry, an icon of black activist Los Angeles who witnessed white resistance to school integration and the Watts and 1992 riots without losing faith that hard work and outrage would manifest racial justice, has died.

Aubry, 86, died May 16 after a short illness, writer Erin Aubry Kaplan, one of his five children, said. A writer as well as an activist, he composed more than 1,700 hard-hitting columns over 33 years for the Los Angeles Sentinel and served two terms on the Inglewood School Board.

But it was his decades of social, political and community activism on issues including black education, job training, police accountability, fair housing and reparations that shaped his life. The groups he helped found or lead spanned the early civil rights era of the 1960s to Black Lives Matter, and included Advocates for Black Strategic Alternatives, which most recently fought to expand rent control, and the Black Community Clergy and Labor Alliance, which has worked on housing and charter school issues.

“When I was young and asked my mom what he did, she said he went to meetings,” said Aubry Kaplan, who is a contributing writer to the L.A. Times’ Opinion section. “It took a while to understand what he did and why it was bigger than us as a family.”

Aubry mentored generations of African American activists, some of whom went on to win elected office. But he also helped guide and support younger activists who believed that the black leadership had grown complacent and too accommodating to the status quo.

“Larry was very much the godfather of South-Central Los Angeles,” said Damien Goodmon, founder and executive director of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition, “not in the sense of a kingmaker, but as the conscience of black L.A.”

Aubry worked from an “unapologetically black perspective” -- his words -- but helped lead a rainbow of multicultural collaboratives before they were called that. “It was never either/or for him,” Aubry Kaplan said. “There was a lot of subtlety to him.”

He did not hesitate to call out allies, former and current, whom he felt had abandoned their obligation to represent the black community’s best interests -- at times in an audible tone during public sessions.

“Larry didn’t know how to whisper,” said Melina Abdullah, founder of Black Lives Matter. “He would tell everything just as it is, and he wasn’t shy about it. “

“My father always said, ‘I don’t have friends. I have issues,’ ” said Aubry Kaplan. “His card read, ‘Larry Aubry ... black issues,’” Goodmon laughed. “That was his card!”

In his columns and interviews, he said repeatedly that it would take the “sustained righteous outrage” of the 1960s plus action to change social conditions. He never lost that passion, friends said.

Born in New Orleans, Aubry arrived in Los Angeles at age 9 and soon found that segregation in pools and restaurants had followed him here. With racial housing covenants falling, his mother transferred him from all-black Jefferson High to nearly all-white Fremont High because she thought it was a better school, he told Times columnist Steve Lopez in 2005. Aubry said he was petrified.

“There were signs out front that said, ‘No Niggers.’ ” Aubry said. “The community and students were there with banners … and on the school grounds, tar babies were hanging in effigy.”

From that seminal experience his activism was born, Aubry Kaplan said. “He was impatient with the idea Los Angeles was so much more enlightened,” she said. During the Watts riots, he watched police shoot at looters outside an appliance store.

An old jazz hand, he played the trumpet, first professionally and later informally. The lingo resurfaced in his reaction to President Trump, Aubry Kaplan recalled.

“He’d say, ‘Wow. That guy is just way out there,’ ” she said. “I thought that was just perfect.”

Aubry graduated from UCLA in psychology, then started a master’s program at USC, but left without finishing to get into the streets and start working.

“Grass roots was his thing,” Aubry Kaplan said. “He didn’t sit around and pontificate.”

He worked in social services, including probation. His day job for 34 years was as consultant to the Los Angeles County Human Relations Commission, formed to promote interracial progress after the so-called “Zoot Suit Riots” of 1944, which saw mobs of white military men beat up Latinos in the streets of Los Angeles for several days running.

L.A. County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas said he worked with Aubry on black issues for four decades. “He was a substantial presence,” Ridley-Thomas said. “You might have called him ubiquitous.”

Goodmon remembered a no-holds-barred school board election in which Ridley-Thomas and Aubry backed different candidates. The rhetoric turned rowdy; Ridley-Thomas was accused of trying to steal a board seat.

“The next day the picture in the paper was of the two of them laughing in front of the school board,” said Goodmon. “He was a very serious man, but he was also really funny.”

Maulana Karenga, chair of the Africana Studies department at Cal State Long Beach and creator of the Kwanzaa celebration, said he first worked with Aubry on the Opportunities Industrialization Center, a national effort started in the 1960s to train the urban poor for jobs their color had denied them. More recently, they co-chaired the Black Community Clergy and Labor Alliance.

“As a community leader, he saw leadership as a moral vocation and acted accordingly,” Karenga said in a statement on Aubry’s death.

“Larry Aubry was a rarity in a city in which discussions of race are too-often guarded or hedged,” L.A. City Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson said in a Facebook post, adding that Aubry was one of his mentors.

Aubry mourned the erosion of black unity after integration and said that African Americans had internalized white people’s individualistic, capitalist values -- without their resources. But he never retreated to cynicism.

“He was frequently disappointed but never discouraged,” said Aubry Kaplan. “To the end he was still joining groups and starting groups.”

“He saw what freedom could look like, what justice could look like and he was convinced we could have it,” Abdullah said.

In his final Sentinel column 13 months ago, Aubry mused, “Some might wonder why I’m stopping now, but others might wonder how and why I kept on going so long?” Then he answered his own question.

“I say a kind of farewell, for real soldiers never really quit, they just move to other positions on the battlefield for the justice and good life we all deserve and will eventually achieve through unity, strength and determination.”

He is survived by his wife of 64 years, Gloria, and children Aubry Kaplan, Arhomuz Aubry, Kelly Cormier, Kris Aubry and Heather Aubry.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.