Rural California is reopening despite little coronavirus testing. Is it too soon?

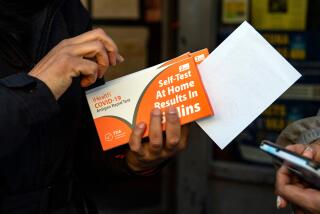

Bolstered by new coronavirus testing sites recently opened by the state, 23 rural California counties this week began to shake off some of their social restrictions and resume a semblance of pre-pandemic life. More are expected to follow.

But testing in many of those places has been slim, both due to a lack of access and demand, leaving questions about how much the coronavirus is circulating in communities.

“It’s hard to say just how much hidden disease is out there,” said Aimee Sisson, public health officer for Placer County, just north of Sacramento, where restaurants and some retail stores are allowing patrons back with new protections.

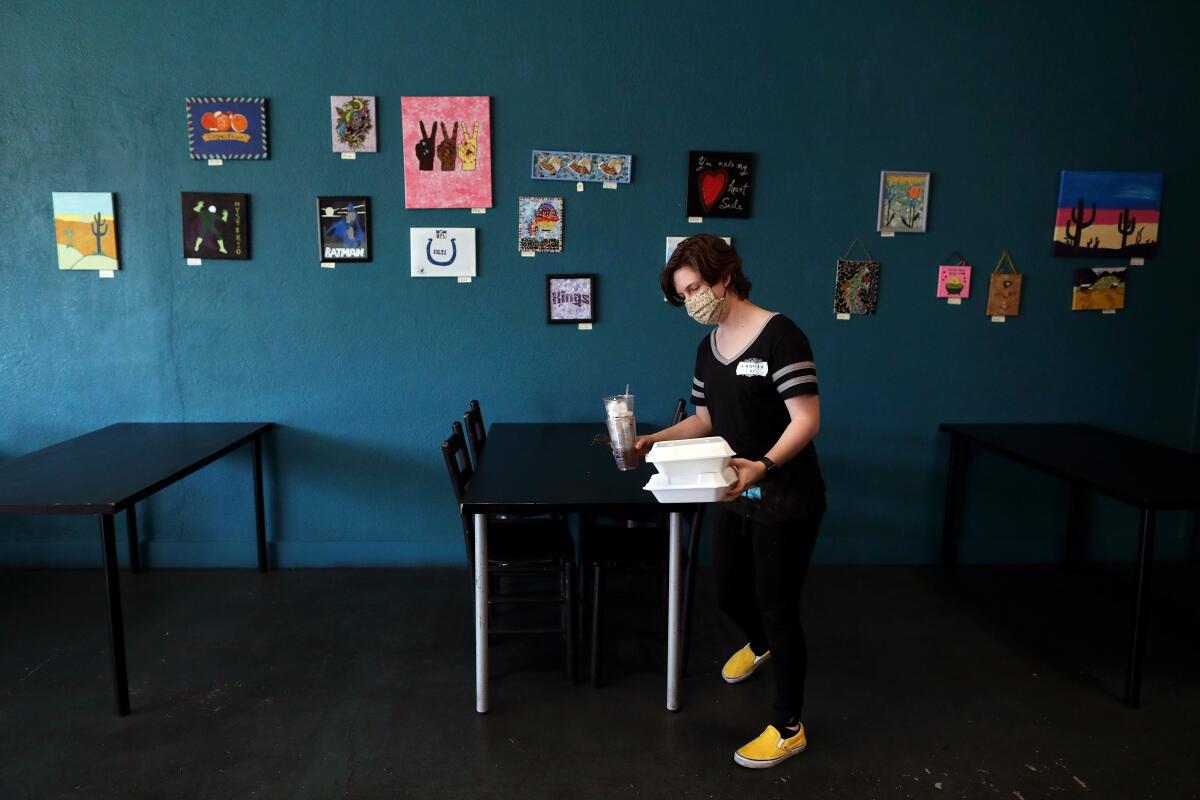

11 photos: Businesses and restaurants open to customers in rural California counties.

California is engaged in an unprecedented statewide experiment, easing off social-distancing restrictions in some places, while keeping them firm in others.

If it works, some Californians will be able to restart businesses and jobs and rebound from the pandemic’s economic carnage. If it fails, the virus will swell in parts of California so far untouched, spreading the heartbreak into rural communities, many of which were impoverished before the pandemic.

Williamson Memorial Hospital did not treat any COVID-19 patients, but the coronavirus wreaked a devastating financial blow, causing ER visits to plummet.

Throughout the state, as the inequity of opening takes shape, tensions will likely grow.

“People are probably of the mindset that when everyone is in it together, the entire state is in it together, they are willing to put up with it,” said Jeffrey Klausner, professor of epidemiology at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. “What we are obviously seeing is this home confinement fatigue and people are just kind of irritated and anxious.”

An analysis of available data by The Times suggests that testing is still largely concentrated in urban, coastal areas — and that despite the capacity to test, the number of people being swabbed in many counties planning to reopen remains small.

To gain state permission to restart businesses, counties had to demonstrate they could handle outbreaks — including the ability to test widely. For most rural counties, that capacity wasn’t available through county health labs and private facilities.

But California in recent weeks has helped counties create about 90 new testing sites statewide — a secretive effort that saw sites pop up with little public notice, despite requests from The Times for details.

That new testing capacity has unexpectedly given rural counties ammunition to argue they meet the criteria to reopen, even where there has been little local interest in getting tested.

President Trump issued remarks Friday that both reflected — and encouraged — the resistance to more testing nationwide.

“When you test, you find something is wrong with people,” said the president. “If we didn’t do any testing, we would have very few cases.”

Many of the counties requesting permission to partially reopen — what Gov. Gavin Newsom has dubbed “Phase 2” — are depending on those new testing sites to reach required benchmarks. But since the state has opened new testing sites only in the last days or weeks, counties have conducted only a few thousand tests across the region.

11 photos: Businesses and restaurants open to customers in rural California counties.

In Shasta County, where the population is about 180,000, health officials say they have the capacity to test more than 4,500 people per week — meeting the state mandate of being able to test 1.5 people per 1,000 residents for the fast-track approval.

But a snapshot of that testing for the first week of May shows that the county ran a total of 683 tests, or less than 100 per day. It had supplies on hand to run only about 1,500 tests, according to documents submitted to the state.

Yuba and Sutter counties, which turned in a joint application for a variance on state orders, said 2,223 tests had been conducted on residents, testing an average of 59 residents a day in the past week, below state mandated levels. County officials cited low incidence of the virus and low demand for testing in justifying their request to partially reopen.

In Tuolumne County, which includes part of Yosemite National Park and has seen only two coronavirus cases, the county is reporting about 13 tests daily. Though this falls far below the mandated level of about 82 tests per day, county officials argue that the county’s low case count and hospitalization rate mean it should be eligible for a variance.

County health officials said that part of the difficulty in ramping up testing is that residents resist it.

While California’s biggest urban areas — Los Angeles and the Bay Area — have taken a significant hit from the coronavirus, the northern part of the state, home to a large number of counties that are reopening, has been nearly untouched — about 20 people there have died from the virus.

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in California.

Three counties — Lassen, Sierra and Modoc — haven’t reported a single case, despite being home to multiple state and federal prisons and other institutional settings, hot spots for the virus.

Still, Dr. Sonia Angell director of the California Department of Public Health and State Health Officer, said essential services in rural counties are “less readily available,” making testing and other preparations essential.

Lassen County Public Health officer Barbara Longo acknowledged that despite not having any positive tests, her county currently is a testing desert. About 160 tests have been conducted so far, giving it the lowest per capita testing rate in the state, according to a Times analysis.

“A lot of it is people just aren’t presenting [symptoms],” she said, “If they are not sick they just don’t have a desire, I guess, to get tested.”

She hopes that will change next week. She said the state, in partnership with Silicon Valley testing company Verily and UC San Francisco, is flying in more than 16,000 tests and will conduct a massive surveillance testing effort that she hopes will include almost every nonincarcerated person in the county.

State health officials could not immediately say why Lassen had been chosen for the large effort.

More than a third of Lassen’s residents reside in two state prisons and one federal correctional facility, and many workers at those institutions live 85 miles away in Reno, she said, increasing the chance of exposure despite the “real frontier” setting of the county.

But Longo said she is unsure how many residents will be willing to submit to the test.

“I don’t know how they are going to receive it but we are going to be really pushing it as a positive thing,” she said.

Her message, she said, will be, “We want to stay safe. To keep yourself safe, we need to know what we really have here.”

Lassen isn’t alone in its skepticism. In nearby Shasta County, more than 2,000 people gathered for an unauthorized rodeo, prompting a rebuke by the county health director.

“There are people who believe their Constitutional rights are being violated by the shutdown and we should open everything up and not care what the Governor says,” said Kerri Schuette, public information officer for the Shasta County Department of Health and Human Services.

Placer County’s Sisson said that the notion of surveillance testing can be a “scare” for some, making it language she’s “trying to get away from.”

She has received threats because of county health orders.

“I was told, ‘We know what you are doing ... The patriots are watching. We are coming after you,” she said “The same caller was concerned that our hospitals were empty. I don’t think they used the word hoax, but that was the idea, that this was all sort of made up.”

Sisson, Longo and others point out that despite the low numbers of tests, other indicators, such as low hospitalizations, support the argument that the virus in not widespread in their areas — adding both to the challenges of enforcing social distancing and the case for restarting businesses.

Since the pandemic started, Schuette said only eight people have been hospitalized in Shasta. “It does not appear that there are a multitude of people that are carrying this,” said Schuette.

While rural areas seem to have so far escaped the worst of the outbreak, county officials know they being watched closely by state government and their neighbors to the south.

The dangers of minimal rural testing were recently illustrated in Kings County, where health officials were unable to detect early a coronavirus outbreak at the Central Valley Meat Co. in Hanford. Last week, after encountering some “logistical difficulties,” the state helped create a testing site aimed at checking plant workers. But it came too late to prevent widespread contagion. As of Wednesday, more than 200 employees had been infected.

In Placer County, Sisson said the new sites have “been a transformation for us. It basically doubled our testing capacity.” She and others expect to see an uptick in cases, but believe they can be contained.

Sisson is planning to test 20% of all staff and residents of skilled nursing facilities on a weekly basis to prevent an increase. If a positive case is found, every person at the facility will be tested and positive cases traced, she said.

In Shasta, health officer Karen Ramstrom this week urged employers to take advantage of the new capacity to test by sending employees on a regular basis, such as every two weeks, whether they are sick or not.

Ramstrom said during a briefing her goal is to keep any new cases at “a slow simmer, not a full boil.”

But if Shasta and other rural counties are successful at what Sisson says is largely “an experiment,” some experts fear it will create pressure for others to follow suit too soon, and feed perceptions the virus isn’t as bad as the science shows.

“North California, it’s kind of like a different animal. It almost feels like a different country,” said Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist at UCSF. “I’m worried people will look at it and say, ‘Hey look, nothing happened. We can do it too.’”

Sacramento bureau reporter Patrick McGreevy contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.