Tracing coronavirus origins is vital to moving forward. But there’s a catch — several, actually

It was early February when signs of something alarming turned up in the heart of Silicon Valley. Santa Clara County emergency rooms had a surge of patients with flu-like symptoms. Yet 30% of them tested negative for influenza, triple the usual rate.

Something else was making people sick.

That something, some researchers now suspect, was COVID-19, which lurked in the San Francisco Bay area for weeks before anyone suspected it had arrived in the United States. Efforts to trace the virus backward in time, however, have been frustrated by roadblocks: delays in setting policies for testing the dead, a single national lab able to do that work, and a fractionalized coroner system that creates large blind spots in the hunt for origins of the pandemic.

It took 11 weeks of looking elsewhere and lab delays before health officials confirmed that a San Jose woman died Feb. 6 of COVID-19 — making her the first documented death from the virus in the United States.

It was another week before California health authorities followed through on an April 22 promise by the governor and instructed coroners to look for more missed cases.

Weeks later, aside from the work already begun in Santa Clara County, there is no evidence any coroner is yet doing that. Some coroners are not even sure they have autopsy samples from the right organs and preserved the right way.

New information emerging in the past week in California paints a very different picture of the spread of novel coronavirus than the one suggested by the first, official version.

“If I can’t send proper tissue, I can’t test,” said Sacramento coroner Kim Gin.

Others are unsure they have the legal right under state law to open closed cases.

“Going back is research, which is a violation without authorization,” said San Mateo coroner Robert Foucrault, putting him in disagreement with other coroners interviewed by The Times.

Even if they begin sending samples to the only lab in the United States available to them for testing autopsy tissue for COVID-19, the majority of California medical examiners and coroners consider hospital deaths and other medically-attended deaths outside their jurisdiction. Coroners are responsible for determining the cause of death for those who die outside the medical system, such as homicides or people found dead in the street, though state law includes contagious disease deaths under their authority.

“Yes, COVID-19 is a contagious disease constituting a public hazard, but the hazard has been mitigated in these [hospital] deaths,” said Dr. Christopher Young, the Ventura County medical examiner. By identifying patients with the virus, Young said, hospitals alert family members and prevent further exposure.

But cases examined by The Times illustrate how easily the virus slips past the medical system, leaving its victims to die at home. They include Alfonso Ye, a 25-year-old pharmacy technician who sought treatment for a high fever and fainting spells at a San Diego hospital on March 17. He tested negative for influenza and was diagnosed with a viral infection in his lungs, and was sent home with acetaminophen and ibuprofen. He died in his mother’s house seven days later; the coroner determined that COVID-19 had been the cause of death.

Researchers believe there is a large undercount of COVID-19 fatalities. The CDC this week released findings that more than 5,300 people might have died in New York City from March to May of undiagnosed COVID-19. Yale researchers calculate one out of three COVID-19 deaths in New York are missed, and that by April nearly 1,000 Californians died of the virus without its detection.

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in California.

COVID-19 cases are spread unevenly in California, clustering in parts of the state and skipping others. Yale study author Daniel Weinberger said such “noise” in the state-level data likely masks what is happening in individual regions like Santa Clara County.

The search for missed cases is crucial to discovering the origin of the virus in the United States and understanding its rate of spread and deadliness. It also feeds public policy and politics. California this week began basing decisions on allowing counties to reopen shuttered businesses on whether they have had any diagnosed COVID-19 deaths in the prior two weeks.

“If we have incorrect numbers, if we’re undercounting both deaths and infections, we’re going to make bad public health decisions about reopening,” said Judy Melinek, a pathologist whose contract work includes Alameda County’s coroner’s office. She advocates aggressive efforts to test backward in time for the virus.

“And then if we have bad numbers, it also means once we were open, we’re not going to pick up the secondary surge.”

Melinek reviewed the autopsy of Patricia Dowd, the 57-year-old woman who death at home is currently considered the first COVID-19 fatality in the United States. She said the degree of damage to Dowd’s heart muscle indicates the virus had ravaged her body for weeks. That put Dowd’s infection on a timeline that suggests she was exposed to the virus in early January, within a week of China’s Dec. 31 announcement of a never-before-seen virus causing people to become ill in Wuhan City.

Genetic studies currently surmise the virus made the hop — likely from bats — to humans as early as late November 2019.

Efforts to contain the virus in late January through U.S. airport screening failed. A CDC report says that of more than 12,000 travelers arriving in California from China, the state was aware of only three that developed COVID-19. The state could not say if the majority of travelers escaped the virus — they had vanished off the radar.

A UC San Francisco researcher said the presence in Santa Clara County of a telltale genetic mutation in SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, suggests the area was an early entry point on U.S. soil, arriving in California before or at the same time as the first case the U.S. did detect — in a 30-year-old man who flew from Wuhan to Washington on Jan. 19.

Dr. Charles Chiu cautioned against the notion of a single “patient zero” setting off the U.S. outbreak.

“We’re thinking that what happens is that you have viruses of different lineages that get constantly introduced through travel,” Chiu said. “You can think of it as sparks being thrown off by a flame. Some of the sparks may catch, and some of the sparks may be put out very early.”

The Times found that cases of Santa Clara County residents seeking treatment for flu-like symptoms also surged in early February, the week that Dowd died.

Thirty percent of them tested negative for influenza, triple the usual rate.

It is possible they were sick with other common diseases. No information was available on testing those patients for other viruses circulating at the time, such as rhinovirus, the common cold.

But directly across the bay in San Francisco, the University of California, San Francisco hospital says 10% of those who sought treatment there for flu-like symptoms in February and March had COVID-19. They were, in fact, more likely to have COVID-19 than influenza, rhinovirus or metapneumovirus, UCSF researchers said in a recent study.

The Times also analyzed death records reported to the Santa Clara County medical examiner. They show a spike in pneumonia and influenza-related deaths in early March, a week before the county began also seeing increased deaths from COVID-19. The surge rose far above the number of similar deaths during the flu season the year before.

At the time, however, federal and state policies restricted who was eligible to be tested for COVID-19. The danger was believed to be limited to exposure to foreign travelers.

Santa Clara County Medical Examiner Dr. Michelle Jorden, who answered questions by email, said her pathologists suspected as early as February they were handling COVID-19 deaths.

Jorden said her office waited a month, running tests to rule out influenza and other pathogens, before sending the samples to the CDC in mid-March.

Other Bay Area pathologists were taken by surprise by the discovery of a COVID-19 death nearly three months before. They said Jorden had not warned neighboring counties of the suspected COVID-19 deaths.

The discovery has spurred epidemiologists, pathologists and microbiologists already working within their own disciplines to understand the hidden spread of COVID-19.

The populace at large is pressing other questions — when is it safe to lift quarantines, and whether a horrible bout with flu last winter was really COVID-19.

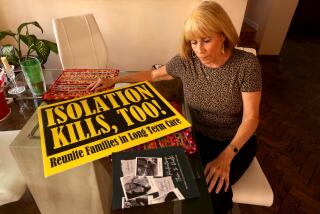

Darryl Ospring suddenly wondered anew about the rapid death of her mother.

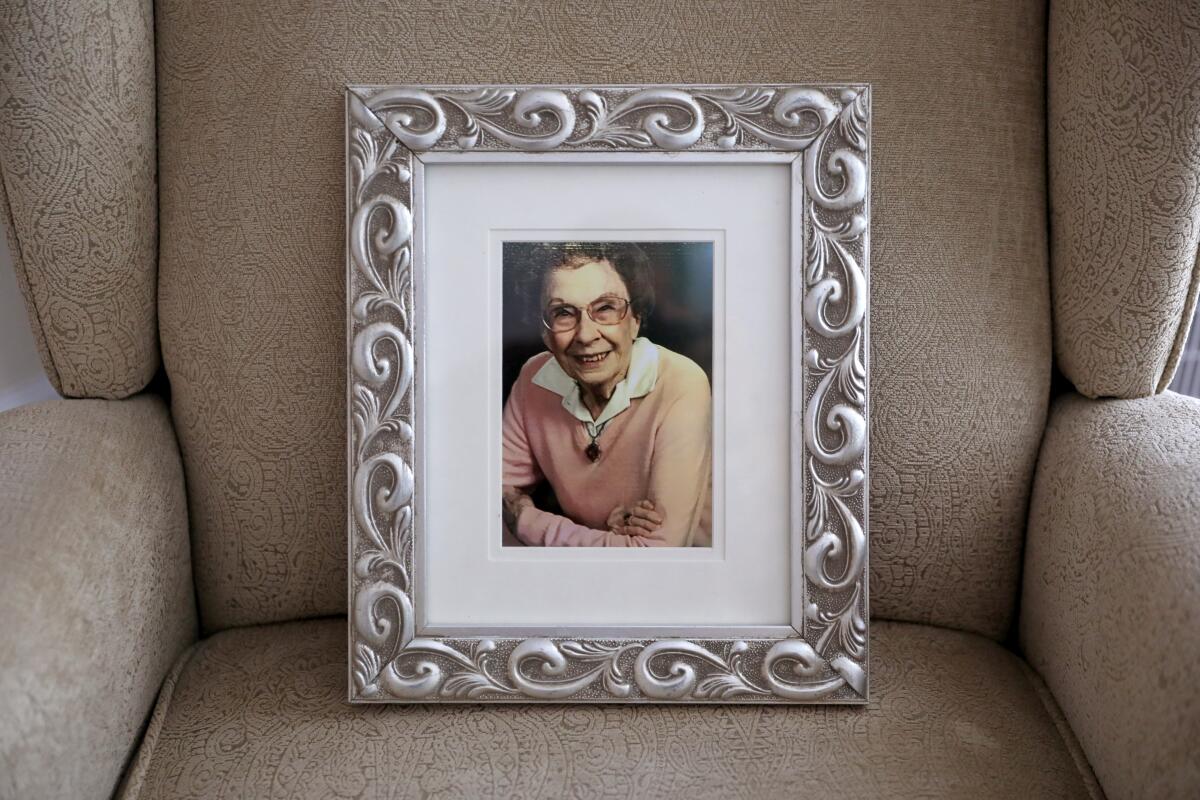

Marjorie Waggoner, 98, lived in an assisted living facility in San Jose. She was remarkably healthy but suffered memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease. On Jan. 8, she grew tired, lost her appetite, and soon developed a cough, then a fever. By Jan. 22, Waggoner was dead, the cause attributed to “complications” of neurodegenerative disease.

“I was in shock to see how quickly my mother was attacked by something,” Ospring, said. “And it confused everybody.”

Ospring received her mother’s ashes and, with the news about Dowd, something else.

Questions.

“At the time I thought, ‘Gosh, I’m so glad she passed away quickly and missed all this COVID-19. Now I’m thinking she probably did have it.”

At an April 22 press appearance, the day after news of Dowd’s death, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a “directive” for other California county coroners to look for other early deaths by the virus.

A Times investigation shows that it was a week before the directive was actually issued, asking for testing of cases from Dec. 17 through March 16, but excluding hospital deaths after March 4 or deaths of those who had been to China.

Even now, the search has yet to begin.

Coroners and medical examiners including the one in Los Angeles County said they are waiting for local health departments to decide which cases to test. Approval must then be sought from the state Department of Public Health and the CDC — which pathologists said currently operates the only lab in the United States conducting such testing, outside of the military.

Los Angeles County’s medical examiner is swabbing selected cases for the virus, and so far has detected COVID-19 in 30 deaths. It has sent the CDC a single tissue sample, to check for COVID-19 in a case where the nasal swab results were inconclusive. Case files analyzed by The Times show cause of death has yet to be determined for more than 480 people who died in the past two months. What is already very clear is a dramatic surge in deaths at home — up 30% over 2019.

Early on, the CDC appeared to warn coroners against sending samples that had been preserved more than two weeks. The federal agency clarified its guidance last week to say the limitation applies only to tissue immersed in formalin, a lab mixture of formaldehyde and water.

Neither the CDC nor the California Department of Public Health answered repeated questions about postmortem testing. The state health department also did not respond to requests for public documents under California’s Public Records Act.

A similar request to Santa Clara County also was refused. A lawyer for the county said it was “not in [the] public interest” to spend time producing copies of communications between the county, state and the CDC, nor to provide the pathology reports that had been returned to the county.

(A public records audit by The Times showed that in the first two months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state health department rejected or failed to respond to every record request related to the virus. The agency told one news organization that emails with the CDC and health departments were “exempt from disclosure.”)

There is no uniform policy at a national or state level on testing the dead for COVID-19.

California’s policies have taken shape over the past two months in a fragmented system of medical examiners and elected sheriff coroners.

Decisions on whether to test the deceased run the spectrum, from test-practically-everyone to test-practically-no one. Two counties, Fresno and Stanislaus, said they had each tested a single deceased person for the virus.

Other medical examiners said they began routine swab tests for COVID-19 in early March but limited them to those who had flu-like symptoms or were found dead on the street.

Tissue testing has the capability of revealing if COVID-19 was killing patients “that we just didn’t know at the time because we weren’t looking,” said Dr. Jen Dien Bard, the virology lab director at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles. However, she said she did not believe there was much demand in the United States for postmortem tissue testing of COVID-19.

Elsewhere in the world, hospital lab directors are actively testing past patient samples to look for the hidden spread of COVID-19, and conducting their own tests using diagnostic kits already widely available in the United States.

In Milan, Italy, a lab director said he used a test kit bought from Salt Lake City to confirm COVID-19 in tissue from the tongue of a past cancer patient.

Outside of Paris, another researcher used similar testing on preserved respiratory samples to find COVID-19 in a 42-year-old fishmonger treated in December for flu-like symptoms — thus establishing that France had its first confirmed COVID-19 patient days before China publicly acknowledged the virus.

Other deaths show all too well how easily COVID-19 infections slip through the medical system, with disastrous results.

The week after Patricia Dowd died, a 69-year-old San Jose hotel security guard succumbed at home, dying outside of the medical system. His COVID-19 infection also was not confirmed until April.

Even as he died, a 68-year-old woman who lived nearby suddenly began to tire, then cough. Azar Ahrabi came home from an urgent care clinic with prescriptions for two antibiotics, said her son, Amir. Antibiotics are used to control bacterial, but not viral, infections.

She was hospitalized the next day, but it was days before an infectious disease specialist came on scene and insisted Ahrabi be tested for COVID-19.

She died soon after, Santa Clara County’s first official death from a virus that had been killing residents for a month.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.