A widow believed coronavirus killed her husband. It took weeks to learn the truth

For Julie Murillo, the fight to get her husband tested for COVID-19 lasted twice as long as his battle with the illness itself.

Julio Ramirez fell sick March 8 after returning from a trip to Indiana for his job as a sales representative for a jewelry company. Fearing he’d been exposed to the coronavirus, the 43-year-old sought care, but doctors refused to test him on two separate occasions, instead giving him medication and telling him to rest at his San Gabriel home.

He died there March 16.

Nearly three weeks later, after a campaign by Murillo that included calling government agencies and hiring a private autopsy firm, a team from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health visited the funeral home where Ramirez’s body was being kept. Test results confirmed what Murillo had suspected: Her husband had contracted the coronavirus.

As public health officials struggle to get an accurate picture of the coronavirus outbreak, much attention has been paid to how limitations on testing have caused the reported number of cases to be artificially low. But deaths can also slip through the cracks and escape official tallies — at least in the absence of a savvy loved one who becomes an advocate for the dead, like Murillo.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health works closely with the county’s coroner’s office to test suspected COVID-19 cases postmortem.

“I can give you assurances that even when there’s testing that happens unfortunately after someone has passed away, those results are reported to us and they are included in our daily tabulations of the number of people who have died,” health department director Barbara Ferrer said.

The majority of deaths in L.A. County are not handled by the Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner. The coroner’s office investigates 15% to 20% of the county’s roughly 60,000 deaths each year, according to statistics released by the health department in 2019. The rest are handled by hospitals and mortuaries.

When a person dies of natural causes while under the care of a medical professional, either at home or in a healthcare facility, the coroner generally doesn’t get involved and the treating physician signs the death certificate.

The physicians are required to denote whether COVID-19 played a role and to report all such deaths to the Department of Public Health and the coroner’s office. They also must report deaths of presumed COVID-19 cases, according to guidelines released by the health department last week.

“In general, patients who die are assessed similar to all patients,” the Department of Public Health said in an emailed statement. “If the individual had symptoms consistent with COVID-19 the clinician may approve testing. This has been done on a number of cases.”

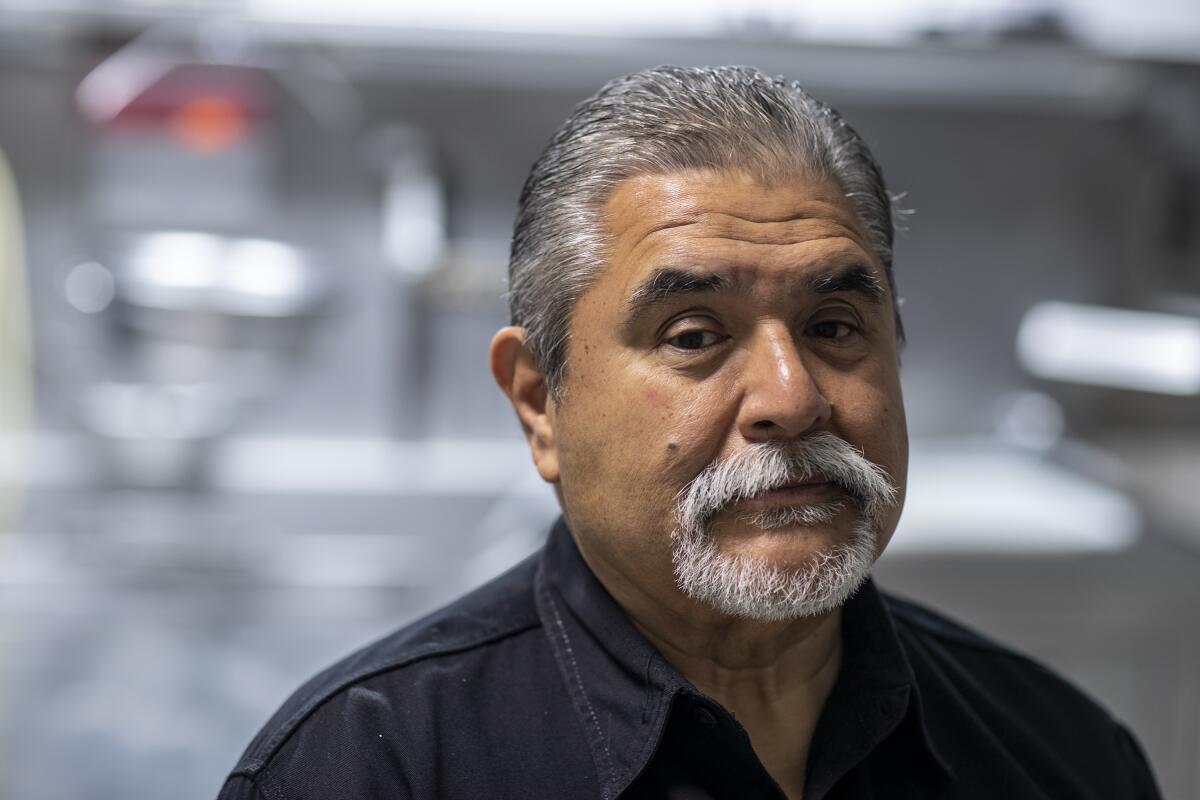

But that doesn’t appear to be happening uniformly, according to Vidal Herrera, a retired deputy field investigator for the county coroner’s office who now owns a private autopsy business in East Los Angeles.

Herrera said his firm, 1-800-Autopsy, has been flooded with requests from scores of people whose loved ones died and were not tested for the coronavirus. During one especially busy time, he said he received 50 to 60 calls in just a few days.

“The families, they just want to know, ‘Did my family member die of coronavirus? The hospital is not telling me,’ ” he said. “Many times they rubber-stamp a cause of death. We see things like respiratory failure attributable to pneumonia.”

Coronavirus might have been in California as early as December. The timing had dire consequences

The day after Ramirez developed a fever, body aches and a dry cough, he called Kaiser Permanente, his healthcare provider. A doctor evaluated him over the phone and wrote him a prescription for Tamiflu and cough medicine, Murillo said.

When Ramirez’s condition continued to decline, Murillo took him to Kaiser’s Downey Urgent Care center on March 13.

By then, the struggle to breathe had left her husband so weak that she had to push him in a wheelchair.

A receptionist first took the couple’s cellphone number and directed them to an area for people with flu-like symptoms. A doctor then called and evaluated Ramirez by phone. The questions seemed narrowly focused on the extent of his travel and whether he’d been outside the country, Murillo said.

The doctor had Murillo wheel Ramirez to another area of the hospital for a chest X-ray, where he was too frail to take off his sweater. Afterward, she pushed him to the pharmacy to pick up cough syrup, antibiotics and an inhaler.

“The only person who saw him was the technician who did the X-ray,” Murillo said. “No one ever touched him.”

The couple were sent home and told to await a call with the doctor’s findings. No COVID-19 test was administered.

A new L.A. County study will use blood tests for antibodies to the coronavirus to give officials a better sense of how COVID-19 has spread, how deadly it is and whether social distancing is working.

Murillo, 42, and Ramirez attended Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights in the 1990s and then went their separate ways. The two later reconnected and married three years ago.

But after Ramirez got sick, they began sleeping in separate bedrooms as a precaution against the highly contagious virus.

Three days after they visited the urgent care, Murillo could not wake Ramirez when she went to check on him. She called 911, and when first responders arrived, they told her he’d been dead for several hours.

“From finding my husband to trying to find a pulse on him to dragging him off the bed onto the floor — it’s just a vision that I can’t shake,” she said.

“Everything is just a blur, what happened. And when I start getting a clear mind, then I start getting upset that maybe somehow this could have been prevented or he could at least have had a fighting chance.”

For more than two hours, no one would come to their apartment to pick up Ramirez’s body. “They kept going back and forth: Is the coroner going to pick him up or the mortuary?” Murillo said.

She eventually was advised that because her husband’s death was considered natural and he was under the care of a doctor, it was not a coroner’s case and she needed to coordinate with a mortuary to have his body removed.

She also learned that the treating physician had signed a death certificate listing Ramirez’s cause of death as pneumonia and there were no plans to perform an autopsy or postmortem testing for the coronavirus.

Kaiser Permanente said in a statement that, at the time, COVID-19 testing at its facilities was restricted to patients who were both exhibiting symptoms and had come in contact with another person confirmed as positive.

“COVID-19 testing was very limited by the government in the early stages of the pandemic, when Mr. Ramirez came to us,” the statement said. “We were required to abide by these public health authority testing limits, as we did in this case, which were based on very limited availability of tests.”

At that point, Murillo vowed to do for her husband in death what the couple couldn’t do while he was alive. Fixing her mind on learning exactly what had happened took the focus off her crushing grief.

“That’s the only thing helping me right now, the fact that I’m trying to get my answers,” she said.

In our effort to cover this pandemic as thoroughly as possible, we’d like to hear from the loved ones of people who have died from the coronavirus.

The mortuary connected her with Herrera, and she hired 1-800-Autopsy to investigate. On March 26, small samples of each of Ramirez’s organs were collected and preserved in formaldehyde.

For suspected COVID-19 cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that some of the samples be sent to its Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch in Atlanta for testing.

But Herrera found that the CDC would not accept tissue samples from his private company. It told him to work with the L.A. County Department of Public Health, which referred him to the county coroner’s office, which told him to call the hospital where the physician signed off on the death certificate, he said.

“It’s like a dog chasing their tail,” Herrera said.

The CDC did not respond to a request for comment. The L.A. County Department of Public Health said that its Acute Communicable Disease Control Program recommends that private autopsy companies work with commercial laboratories for postmortem testing.

But at the time, Herrera was unable to acquire test kits in order to administer a nasal swab and send it to a commercial lab.

So Murillo, who was quarantined without access to a computer, enlisted family members and friends to make phone calls to government officials pleading for a postmortem test.

Sixteen days after her husband’s death, the county Department of Public Health called to say it was sending a team to the funeral home to test Ramirez. On April 4, she learned the results were positive.

Murillo said the discovery hasn’t given her closure, but something bordering on a sense of relief.

“I felt that I finally got an answer,” she said.

Kaiser Permanente said in a statement that limits on who can be tested “have evolved over the past several weeks” and that testing is more available now than it was a month ago.

“We offer our deepest sympathy to the Ramirez family during their time of grieving,” Kaiser Permanente said.

Last week, Herrera was able to obtain swab tests from a doctor he works with who has connections with a laboratory. He said he no longer will pursue COVID-19 testing through the CDC via autopsy. He hopes to roll out the swab testing to clients more widely in the coming days.

“Our mission statement is: ‘The deceased must be protected and given a voice.’ Without a witness, they will be forgotten,” Herrera said. “And right now, we’re witnessing an epidemic and they need answers.”

In a cruel twist of fate, he used the first test on his friend and “right-hand man,” Sean Sadler. The 52-year-old licensed embalmer, who worked for 14 years as Herrera’s chief autopsy technician, died last week after collapsing in his shower.

Herrera said that Sadler had been off work since showing flu-like symptoms the week before. He called Herrera on April 4 to say he was still sick. Three days later, his wife called to say he was gone.

After initially suspecting Sadler had contracted the coronavirus, Herrera conducted an autopsy and tested his friend for COVID-19. The results were negative. The loss stung no less.

“As we say, the circus must go on,” he said, clearing his throat to choke back tears. “Death doesn’t stop for anybody — not for me, not for my employees. We just have to respond as we always have.”

In January, scientists, public health officials and journalists were warning that the coronavirus was set to explode out of China. Few listened.

Murillo is still serving out her quarantine at the apartment she shared with her husband. She closed off the bedroom where he died. Public health officials have advised her not to go inside.

She won’t watch television because the news scares her. She tested negative for the coronavirus once right after Ramirez died. But each time her nose runs or she feels a tickle in her throat, she worries she could be getting sick with the disease that caused her healthy husband to die in a week’s time.

It’s a surreal existence, isolated from those she loves as she tries to process the immense loss. Worst of all, she said, unable to plan a burial and wracked with anxiety, she can’t properly grieve.

“I want to say it’s just a bad dream,” she said. “Did this really happen?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.