So much is unknown about the pandemic because the government keeps a lid on it

It is a tragedy unfolding in real time. At a skilled nursing facility in the Tulare County town of Visalia, 71 residents and 41 staffers have tested positive for the novel coronavirus. Six residents at the 176-bed Redwood Springs Healthcare Center are dead and eight are in acute care, according to Anita Hubbard, the center’s administrator.

But without Hubbard’s details, little would be known about one of California’s worst outbreaks of the deadly virus in a senior facility. Tulare County stopped commenting for five days, during which the numbers of positive cases skyrocketed. Like other cities and counties statewide, California doesn’t require it to release such information, even in the midst of a pandemic.

As the novel coronavirus continues to claim hundreds of lives across California, a secondary victim of the crisis is emerging: government transparency. Much of what we know about COVID-19 in nursing homes and senior facilities did not come from public agencies, but private sources: relatives, staff members and administrators.

Firefighters and law enforcement officers from L.A. to Laguna Beach express their gratitude to healthcare workers for their efforts in fighting COVID-19.

“I want updates,” said Christina Valencia, whose grandmother was among the several people testing positive for the disease at a nursing home in Redondo Beach. “You should have a right to know how many residents are positive.”

Californians are in the dark about more than nursing homes.

Information about the availability of personal protective equipment, or PPE, is lacking, upping the anxiety of healthcare workers. Coroners aren’t releasing information about deaths. Until recently, California was not releasing information about the racial breakdown of people who were infected and killed.

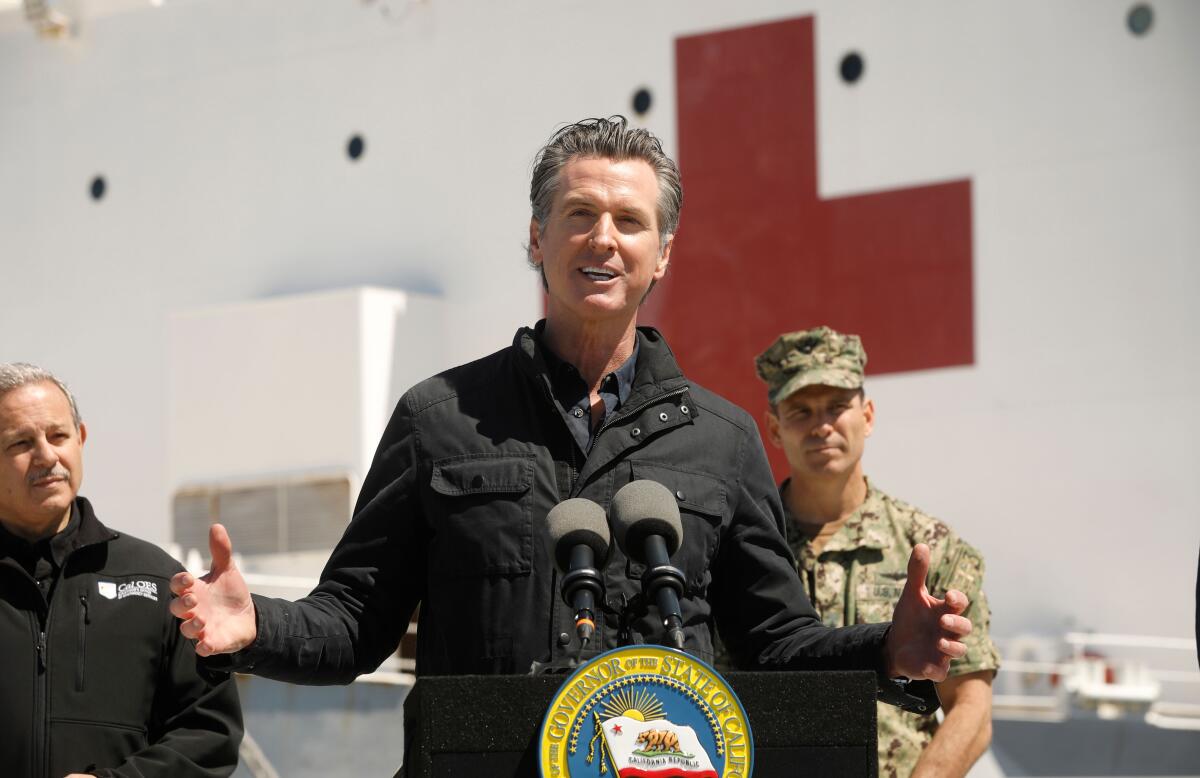

Government confusion has undermined public understanding of the crisis, and has potentially compromised California’s response, some health and civil liberties experts argue. But there are few rules for what cities and counties must disclose and little direction from California’s top officials, including Gov. Gavin Newsom, on what must be communicated in an urgent moment.

Dr. Richard Jackson, who served as California’s state health officer under Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, said it’s crucial that public health agencies and political leaders keep residents informed by sharing data on local hot spots, infection rates and demographics in their communities.

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world.

“As the general principle, the public has a right to important information that would influence their own health,” said Jackson, a professor emeritus at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Such transparency, some experts said, is essential for maintaining public trust amid the catastrophe.

“Mistrust is the enemy of good public policy and certainly good public health policy,” said Jeffrey Kahn, head of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics.

With California waging a blitzkrieg campaign to fight back the fast-moving pandemic, state and local agencies are overwhelmed, and some difficulty sharing information is inevitable. Yet California’s halting release of key knowledge is alarming groups that look out for the vulnerable and disadvantaged.

Last week, the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California sent Newsom a letter requesting more transparency about the pandemic’s effect on people of color and other at-risk groups.

“From what we’ve seen thus far, we know that this virus has been impacting black communities and we have no idea what is necessarily happening here in California,” said Abre’ Conner, staff attorney for the ACLU of Northern California. “We’d like to see more data now, today.”

Conner said the requirement for local data collection and release needs to come from the state, which she argues is best suited to set perimeters, instead of leaving counties and cities to make their own decisions.

“California is really behind the ball in ensuring there is comprehensive data available,” she said. “We don’t have any data, we don’t have any accountability.”

The fallout from inadequate information can be seen not just in Tulare, but in nursing homes and eldercare facilities around the state. Yolo County, home of UC Davis, Monday announced a nursing home there had an outbreak of 35 cases, including 12 staff members and one fatality. But it refused to name the facility, citing privacy concerns similar to Tulare County.

Sacramento and Alameda counties have also come under fire for failing to give details around elder facilities.

By contrast, Los Angeles County has been releasing the names of all elder facilities with a single confirmed positive case since late March.

The dearth of information frustrates family members, who, in at least one case, came close to unknowingly spreading the virus from one senior facility to another.

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in California.

A few weeks ago, a woman named Marcia was hoping to reunite her two elderly parents, who both had Alzheimer’s and had been living in separate facilities because they needed different levels of care. The plan by Marcia, who asked that her last name not be used to protect her family’s privacy, was to move her father from the Alameda Care Center in Burbank facility to the Jewish Home in Reseda, where her mom lived.

Marcia was unaware that an outbreak had occurred at the Alameda Care Center — it happened before L.A. County started releasing information about infections at senior homes.

Fortunately, one nurse in Burbank notified a nurse at the Jewish home because they were friends. The facility quarantined and tested Marcia’s father based on the unofficial advice.

“We got lucky,” said Dr. Noah Marco, chief medical officer at the Jewish Home.

Marcia’s father was less fortunate. He developed the tell-tale symptoms of COVID-19. Four days later, he died, without ever seeing his wife.

In recent days, Newsom has acknowledged the need for greater clarity and access to the data being used to make decisions.

“Understandably people are eager for transparency in real time,” he said during an online briefing. “Every day we are [working] as quickly as we can.”

It’s not just the public that is sometimes left out of the loop.

On April 7, Newsom announced that California had secured a monthly supply of 200 million N95 respiratory and surgical masks to help protect healthcare workers. The governor did not announce the procurement during his daily media briefings, but on “The Rachel Maddow Show.” That left some lawmakers surprised, because they would have to authorize the purchase within days.

“Under normal circumstances, the Legislature would have had more time to deliberate an expenditure of this magnitude,” wrote state Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles), chair of the joint legislative budget committee, in a letter to Newsom last week, asking for more clarity on the terms of the deal.

Mitchell later said in an interview that she supported Newsom’s move and understood the need for speed. But in the letter, she requested the state immediately start a public website to document its inventory of protective gear and where it’s being distributed to ensure supplies wind up where they are most needed.

Tuesday, Frank Girardot, spokesman for BYD, the company that would supply the masks, said it hoped to have quality testing required for federal certifications completed by the end of the month, and shipping could begin then.

The state has yet to respond to The Times’ public record request for the contract. It also hasn’t responded to numerous other records requests, including one seeking information on PPE the state has requested and received from the federal government.

For government agencies, information sharing is fraught with difficulties, partly because of the time involved in collecting data, said Dr. Paul Simon, chief science officer at the Los Angeles County of Public Health. A lack of unified systems is also a problem at the state and local levels.

“We don’t have this one big, massive information system that allows us to share information electronically at a moment’s notice, unfortunately,” Simon said.

Last month, the League of California Cities sent a letter to Newsom asking for a delay of the state’s public records act as “city resources and personnel are stretched thin” during the outbreak.

“Depending on how long the COVID-19 pandemic lasts, cities may not be able to physically access certain records due to office closures, limited staffing, or limited IT capability until they are permitted back into city offices,” said Corrie Manning, general counsel for the league, which represents nearly 500 cities in the state.

Some local governments are halting responses to public records requests. An activist says California’s open records law is more important now than ever.

The governor’s office did not respond to questions about the league’s request.

David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition, said while he agrees that records relating to the pandemic are vital information that should be released, “those are not the only records that matter.”

“There are so many opportunities in a crisis like this for government officials to abuse their powers while everyone’s eyes are off the ball,” Snyder said.

Despite the tremendous stress of the pandemic, public health officials still have an obligation — and a need — to provide information, said Jackson, the state health officer under Schwarzenegger.

“The fastest way to lose your credibility is to give out incorrect information,” he said. “The second fastest way would be to give out no information.”

Times staff writer Melanie Mason contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.