Holy oil, masks and FaceTime: The coronavirus forces Catholics to adapt last rites

As an elderly man lay dying in a Los Angeles hospital last month, his family requested a sacrament that Catholics have asked for down through the ages: last rites from a priest.

But, tradition had to take a backseat to precaution. The dying man had COVID-19 and was in an isolation ward. Visitors were prohibited, even relatives and collared clergy.

The solution the hospital devised owed debts to Steve Jobs and Pope Francis.

A nurse in full protective gear carried an iPhone to the man’s bedside and used FaceTime to patch in the patient’s children in two different locations as well as a priest standing in the hall outside the room.

The cleric explained that the Vatican had given a special dispensation to those suffering from the coronavirus and that the prayers he delivered over the video chat would have the same spiritual effect as if he were to perform the normal anointing with holy oil: a full pardon of all sins.

“Though the circumstances were difficult and unusual, they experienced spiritual and emotional support by this intervention,” according to a description of the event provided to The Times by Providence St. Joseph Health, which runs the hospital where the patient was treated.

By its nature, organized religion is a communal endeavor and social distancing has disrupted its practice profoundly. But due to the coronavirus, most houses of worship are closed, their services moved online or canceled. Scripture studies, weddings, bar mitzvahs, Lenten fish fries and even the annual hajj pilgrimage to Mecca went from set in stone to TBD or not at all.

At a time when deaths have become a national preoccupation, tallied live daily on television, the changes to last rites seem especially poignant. The sacrament, officially called anointing of the sick, exists now in a liminal state not unlike many of those who receive it.

In much of the country, hospitals, including Catholic ones, have decided it is too risky for priests to give the sacrament to those ill from the highly contagious virus. Some have told chaplains to stay away from the hospital and have ended spiritual “rounding” — or paying visits to patients room by room — as part of the effort to reduce spread of the virus.

In other places, the sacrament continues, but with alterations that might make it hard to recognize.

In Boyle Heights, three priests at L.A. County-USC Medical Center suit up in gowns, gloves and masks to administer last rites to virus sufferers. Instead of carrying a large ceremonial vessel, they pour a small amount in a disposable plastic container and dot it on the patient’s forehead and hands with a swab. They pray through N95 masks.

The most profound alteration may be the absence of loved ones at the bedside. In regular times, the rite can be the beginning of the grieving process, with the patient and family and friends sharing memories and expressions of love. With COVID-19, it is often only the priest and a patient too ill to communicate.

“It’s a different form of ministry,” said Father Chris Ponnet, a chaplain at County-USC for 26 years. “The anointing is not a superstitious thing. It’s really where the priest is representing not only God, but the presence of the community.”

When virus patients are lucid, the loneliness of isolation can be oppressive. Catholic deacon Guido Zamalloa counsels COVID-19 patients at Methodist Hospital of Southern California in Arcadia by phone. During one recent call, a 55-year-old woman with the disease described being tired, feverish and anxious about not having her family.

Zamalloa listened and then he and the woman recited the Our Father prayer in unison.

“It’s a spiritual support for the patients,” he said.

The sacrament traces its origins to a gospel description of the apostles: “They drove out many demons, and they anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them.”

Though the faithful use the term last rites colloquially to mean the anointing, the church views it as three sacraments -- anointing, Holy Eucharist and reconciliation, also known as confession. For patients on ventilators or otherwise unable to eat or speak, only the anointing is done.

More than 2,000 Catholic chaplains work in the United States; the vast majority are lay people who provide counseling and bring the Holy Eucharist to patients, but are not able to anoint the sick. The sacrament only can be administered by a priest who is physically present to touch the patient.

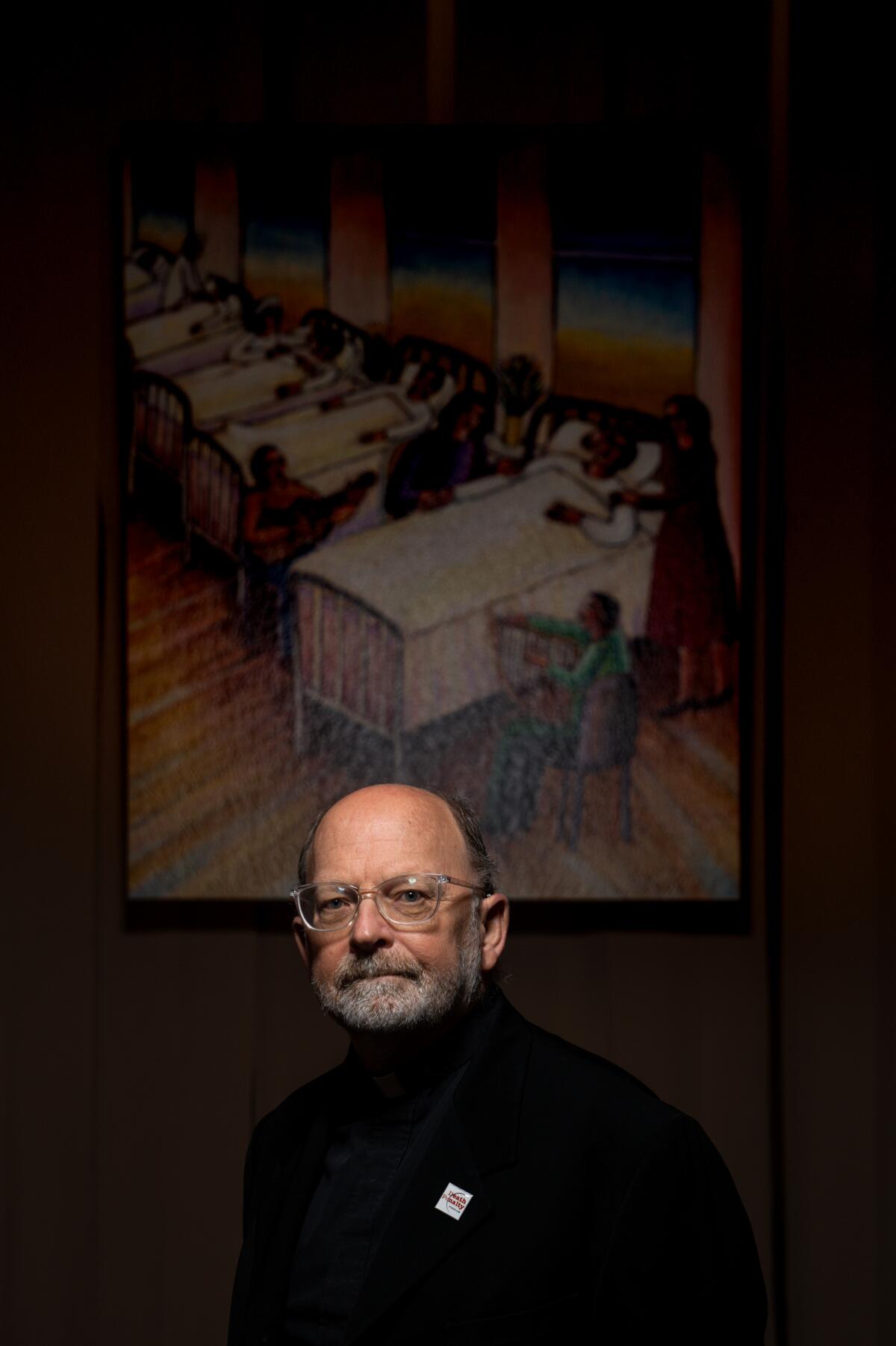

“The Catholic Church is a very tactile religion and the sacraments are very earthy ones, from bread and wine to oil to laying on the hands,” said David Lichter, executive director of the National Assn. of Catholic Chaplains.

In heavily Roman Catholic Italy, which suffered an early and severe outbreak of COVID-19, more than 80 priests have died from the virus. The majority were old and some had underlying health conditions, but the bishop of Bergamo, Francesco Beschi, said in a TV interview that the deaths also testified to the priests’ outreach to COVID-19 victims.

“Numerous are those who have exposed themselves [to the virus] to be close to their community,” he said. “Their illness is an evident sign of closeness, a painful sign of closeness and sharing in the suffering.”

On March 20, the Vatican decreed special dispensations for believers who couldn’t receive last rites or certain other sacraments because of the virus.

It was an unprecedented move that many followers have yet to grasp.

“A lot of Catholics feel like if you don’t get the sacrament of the sick, you are going to be doomed, but that is not it at all,” said Father Timothy Bushy, Southern California regional spiritual health officer at Providence St. Joseph Health, who helped arrange the FaceTime blessing.

A week after the Vatican announcement, Father Lester Avestruz, a Catholic chaplain at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, went from walking the hospital halls to working the phones from home.

While a younger priest continued to minister at the hospital, Avestruz, 74, calls in to about eight patients’ rooms each day.

“It’s a big difference but that is all we can do,” Avestruz said. In the calls, he reassured the ill that because of the pope’s dispensation, they don’t have to worry about not getting the sacraments.

“It gives the patient some peace,” Avestruz said. “I assure them that God is always good and he understands the situation.”

Lay Catholic chaplains and clergy from other religions also have embraced virtual spiritual counseling.

Keck Hospital and USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center are giving out iPads that will allow a chaplain to connect with a patient.

“It’s not the best, but it is certainly better than nothing,”said chaplain Phil Manly, Keck’s director of spiritual care. “The worst thing of all would be to have no communication.”

These days chaplain work also means ministering to medical staff fearful about their own health. The usual hand-waves or “how are yous” often become 15-minute mini-counseling sessions for nurses and other personnel, he said.

“The anxiety levels are so high,” Zamalloa said.

One nurse, he said, came to him recently with her fears. She is pregnant, and the sole provider for her family after her husband was laid off.

“She is debating whether to keep going or not,” he said.

Near the end of March, the Rev. Kevin Rettig was summoned to Methodist Hospital in Arcadia to give last rites to a patient. Hospital staff took his temperature on the way into the building and, once cleared, he went to the critical care unit. A man, who did not have COVID-19, was about to be removed from a ventilator.

Rettig stepped into the room, a mask wrapped around his nose and mouth, to give him the sacrament of the sick. He dipped his gloved hand into holy oil, and drew a cross atop the patient’s forehead and hand.

The man was pulled from life support that day. Though the priest wasn’t present in the room, he believes that the man’s wife and two grown children were there.

“You are there to give a service and it’s an important service,” Rettig reflected later. “You do the best you can under the circumstances.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.