Construction problems delay Metro’s $2-billion Crenshaw Line opening until 2021

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority acknowledged Friday that flawed construction on a $2.06-billion rail line through South Los Angeles will delay its opening until mid-2021, two years later than originally promised.

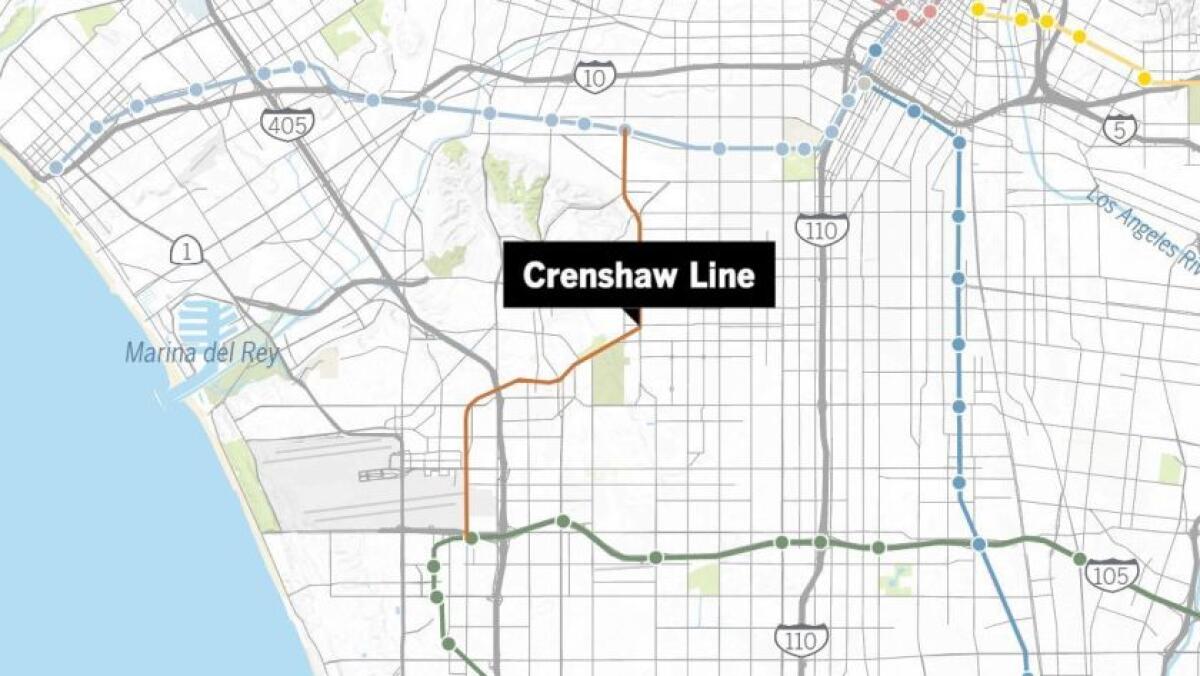

The Crenshaw Line is about 95% complete. But construction will not conclude until the end of this year or early 2021 because crews have been forced to redo work along the 8.5-mile route, Metro officials said.

The issues include settlement in walls that support a rail bridge over La Brea Avenue near downtown Inglewood, and flaws in the steel support structure that is supposed to anchor the train tracks on bridges and in tunnels, officials said.

Once construction ends, Metro will need about five months to test the line and train the rail operators. That means passengers will not be able to ride between El Segundo and Mid-City any earlier than May 2021, officials said.

The yearlong delay is the longest yet for the Crenshaw Line. Once slated for the fall of 2019, the opening date was delayed until spring 2020 after Metro and the contractor wrestled with problems with electrical substations, sidewalks and gas lines.

“We’re disappointed with the schedule,” Metro Chief Executive Phil Washington said in an interview. “Anybody would be.”

Metro plans to ask the agency’s directors this month to approve $90 million more for the Crenshaw Line. Without the increase, according to a draft report reviewed by The Times, Metro won’t be able to pay staff or consultants to manage the project after June.

The proposed budget increase would add about 4% to the project’s cost. The $90 million should cover Metro’s expenses through December, said chief program management officer Rick Clarke. He said the contractor, Walsh/Shea, will pay for some of the work that needs to be redone.

The contractor, a joint venture of Walsh Construction and J.F. Shea Construction, did not return a request for comment.

“We are going to demand a quality project, period,” Washington said. “We are insisting that all of this work gets done and that it actually works. If we have to delay the project, then that’s what we’ll do.”

Washington said it is “becoming more and more difficult” to know when major projects with multiyear schedules will be finished. Metro is currently juggling half a dozen major transit construction projects, including the downtown Regional Connector subway and three phases of the Purple Line subway to the Westside.

The Crenshaw Line delay is a frustration for drivers and bus riders who have waited decades for a more reliable transit option between the Westside and the South Bay. The line will run through Inglewood and the Los Angeles neighborhoods of Baldwin Hills, Hyde Park, Leimert Park and Westchester.

The Crenshaw Line is “undeniably complex,” with street-level, underground and elevated sections of track, said Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who represents most of the project area. But the contractor’s “performance and timeliness has left much to be desired,” he said in a statement.

The Metro board, Ridley-Thomas said, must “do a deep dive to understand what has gone wrong.”

Los Angeles City Councilman Herb Wesson, who is running to succeed Ridley-Thomas on the Board of Supervisors, said residents in L.A.’s “historically disadvantaged communities” will be forced to wait even longer for a high-quality transit option.

Metro currently manages most of the construction projects it funds. Wesson said that “it’s time to consider reopening the discussion” of using independent authorities to oversee major rail projects, similar to groups formed to oversee the construction of the Gold Line and the Expo Line to the Westside.

Metro Chairman and Inglewood Mayor James T. Butts Jr. did not return a request for comment. Nor did Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, the first vice chair of the Metro board.

Concrete slabs that are used to stabilize and anchor the Crenshaw Line’s tracks on bridges and in tunnels were installed incorrectly, Clarke said. The slabs, called plinths, are supposed to be tightly anchored, using steel reinforcements called rebar, to a platform beneath the tracks.

In “a few hundred locations” along the line, the rebar was installed incorrectly, Clarke said. Because the tracks have already been installed on top of the plinths, crews may have to lift up each section of track, fix or replace the rebar, and reinstall the rails, he said.

“I know it sounds bad — it sounds bad to us,” Clarke said. “It’s something that we’re concerned about and watching very closely.”

The contractor is also drawing up plans to fix ground settlement in walls that support a rail bridge over La Brea Avenue, said Anthony Crump, Metro’s deputy executive officer for community relations. He said he did not know the extent of the settlement, only that “it exceeded Metro’s acceptable limits.”

The contractor has said it is safe for Metro to run test trains on the tracks supported by the settling walls, Clarke said, but they will need to be repaired before passengers can ride.

Metro and the contractor are investigating the cause, which could be “unsuitable soil” or flaws in the installation, Clarke said.

Aside from the construction issues, Clarke said, Metro still has a “complicated challenge ahead” in finishing and testing the electrical equipment, communications software and other systems that run the trains. Getting that right, he said, involves connecting more than 8,000 components to the agency’s rail control center.

In 2017, Metro paid Walsh/Shea $55.5 million to resolve schedule problems and avoid litigation over issues during early construction. The settlement included an agreement that the line would open to riders by October 2019.

The following year, Metro reached another settlement with Walsh/Shea to finish construction by Dec. 11, 2019, which pushed the line’s opening date to mid-2020.

This time, Clarke said, there probably won’t be a settlement. “We’re pretty far down the line,” he said. “I’m not sure a settlement at this point would give us confidence that it would get done sooner.”

One of the most highly awaited portions of the Crenshaw Line will open several years after the rest of the route.

A $200-million station at 96th Street will serve as a connection point to a smaller, automated train that will carry travelers and workers to the terminals at Los Angeles International Airport. The stop will also serve as a mini-transit hub, where travelers can board a local bus line, hail a taxi or catch a ride home.

The airport train, called a people mover, is scheduled to open in 2023. The project will cost an estimated $4.9 billion to build, operate and maintain over 25 years, and will be funded through airport revenues and tax-exempt bonds, for which the city’s airport department will pay the financing costs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.