As coronavirus deaths surge, missing racial data worry L.A. County officials

As cities such as Chicago and Philadelphia report stark racial disparities in coronavirus patients and fatalities, Los Angeles County officials say they are scrambling to collect missing data on the race or ethnicity of local victims.

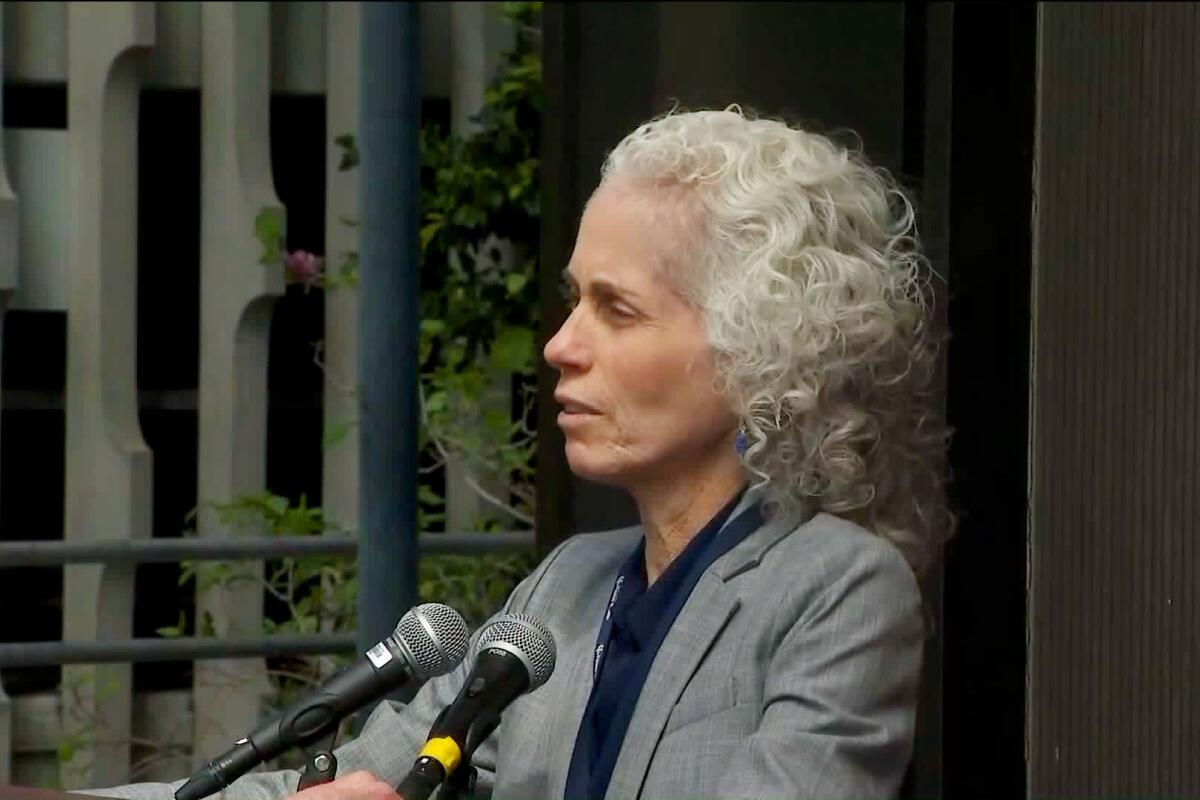

The county’s public health director said Monday she was worried by reports from other states that suggested black patients were being infected and dying of COVID-19 in disproportionate numbers, but that missing data prevented her staff from determining if that was happening locally.

Officials have been unable to get complete information on the race or ethnicity of people hospitalized with COVID-19 because many providers are not reporting it, according to Barbara Ferrer, who directs L.A. County’s public health department. “We’re missing over 50% of respondents filling out that field.”

It’s our visual prompt to stay away, but stay-at-home orders have given new purpose to caution tape.

Data on the race or ethnicity of people who have died are also incomplete, she said. “So we’re trying to pull all of the death records so that we can actually see if we can get better information.”

Ferrer said her team is working hard to determine the demographics of those who have died, as well as hospitalization rates and “potential issues around who was getting tested and who had access to testing.”

“It’s not that we aren’t giving you data that we already have, it’s that we’re looking really hard to get that data ourselves,” Ferrer said.

Recently, a Los Angeles Times analysis found that many of L.A. County’s whitest and wealthiest enclaves were reporting far higher rates of infection than poorer neighborhoods of color. However, public health officials said those disparities did not necessarily mean the virus was spreading more widely through rich neighborhoods than in poorer ones. Instead, the reporting was likely skewed by uneven access to testing and, in some instances, by wealthy residents who traveled internationally and had some of the earliest confirmed infections.

The finding, some experts said, could be bad news for local efforts to control the spread of COVID-19, as it suggests a disparity of testing along the lines of race, income and immigration status that could be obscuring potential hot spots in disadvantaged communities and giving them the false impression that they have less to fear from the virus.

These are some of the unusual new scenes across the Southland during the coronavirus outbreak.

County health officials last week acknowledged “geographic disparities” in coronavirus testing, but said they continue to have difficulties getting complete information on who has been tested. That’s in part because labs have only been reporting positive results, and not negative ones, making it impossible to determine whether the tests are being provided equally across the county.

On Monday, Ferrer acknowledged that the county was still working to understand who is being hit hardest by the outbreak.

“We have a lot of incomplete reporting, and it’s been a challenge,” she said. “So we need to go back now and do some medical record reviews so that we can actually get more accurate information.”

Ferrer promised to make such data available to the public, saying she hopes by the end of the week to have a more complete demographic report, both on deaths and hospitalizations, “that really gives us a better sense of who’s getting sick.”

“As soon as we have that information and we analyze it, it will be available for everyone,” she said.

“We care just as much as everyone about making sure that we address head-on any issues around disproportionality,” Ferrer said. “And we are worried, based on data that’s shown disproportionality in other places.”

Ferrer said African Americans and Native Americans are among the groups in L.A. County that “have a disproportionate burden of illness going into a pandemic” and are “much more likely to have higher rates of almost every illness that we collect information on.”

“Having serious underlying health conditions makes you at much higher risk for serious illness, and even death, from COVID-19,” she said. “So we want to do everything we can to both understand the data, make sure that our communities have access to all the information that we have about any inequities, and then that we work together to try to minimize inequitable distributions of any disease, and certainly of death.”

Officials in other California counties signaled Monday that they are open to releasing demographic data on patients, saying it has simply been a matter of time and resources.

San Francisco’s director of health, Dr. Grant Colfax, said the city will provide a greater level of data about the spread of coronavirus “very soon,” including a data tracker that will provide demographic information, the number of hospitalizations and other details.

A public health department spokeswoman in Santa Clara County, where California’s first large coronavirus outbreak occurred, said that because they were an early epicenter, they have tried to give as much information as possible about who it has impacted most.

Data on patients’ racial and ethnic background could be released in the future, the county said.

Officials in San Bernardino County said that workers would comb through records to compile demographic numbers on coronavirus patients once the outbreak was more under control.

Times staff writer Susanne Rust contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.